2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(12g) Supply Chain Optimisation of Sludge-Derived Biocoal and Hydrogen for DRI-EAF Steel Production: A Case Study

Authors

The steel industry is among the largest contributors to carbon emissions globally, accounting for ~7% of total greenhouse gas emissions worldwide [1]. Approximately 70% of world’s steel is produced using the blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) technology, which is highly carbon intensive as it relies on coal, particularly in the form of coke, both as a fuel and a reducing agent [2]. Iron ore, primarily made of iron oxides, is first reduced to iron in the BF using coke as reducing agent, then sent to a BOF where pure oxygen is used to oxidise any excess carbon and impurities, obtaining molten steel. Overall, a typical BF-BOF plant emits between 1.9-2.3 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of steel produced, with the BF being the main contributor with ~70% of the total direct emissions [3]. Moreover, coke is obtained from metallurgical coal heated up at high temperature (1000-1200 oC) in the absence of oxygen to remove volatile compounds in the coal and obtain near pure carbon coke, which results in additional emissions.

A promising alternative to reduce the steel carbon intensity is via direct reduction of iron (DRI) in combination with an electric arc furnace (EAF). DRI uses either methane or hydrogen as reducing agents instead of coke which lowers the CO2 emissions, while EAF uses electricity as energy source to melt the iron resulting in higher energy efficiency compared to BOF. Currently, the DRI-EAF route has a carbon intensity of about 1.4 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of steel, and further reductions could be achieved through the use of low-carbon hydrogen, biomethane and renewable electricity [2].

Yet another alternative entails the pyrolysis of sewage sludge, the solid residue produced by wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). While sewage sludge contains biogenic carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus, its use as a fertiliser or soil improver is hindered by the presence of pathogens, heavy metals and other chemicals, and it is usually incinerated as a result. Instead, sewage sludge pyrolysis can produce a carbon-based catalyst, which in turn can be used for the catalytic cracking of methane or biomethane from anaerobic digestion [4]. This route would produce hydrogen for the hydrogen-DRI process, while replacing fossil-based coal with the derived biocoal.

Methods

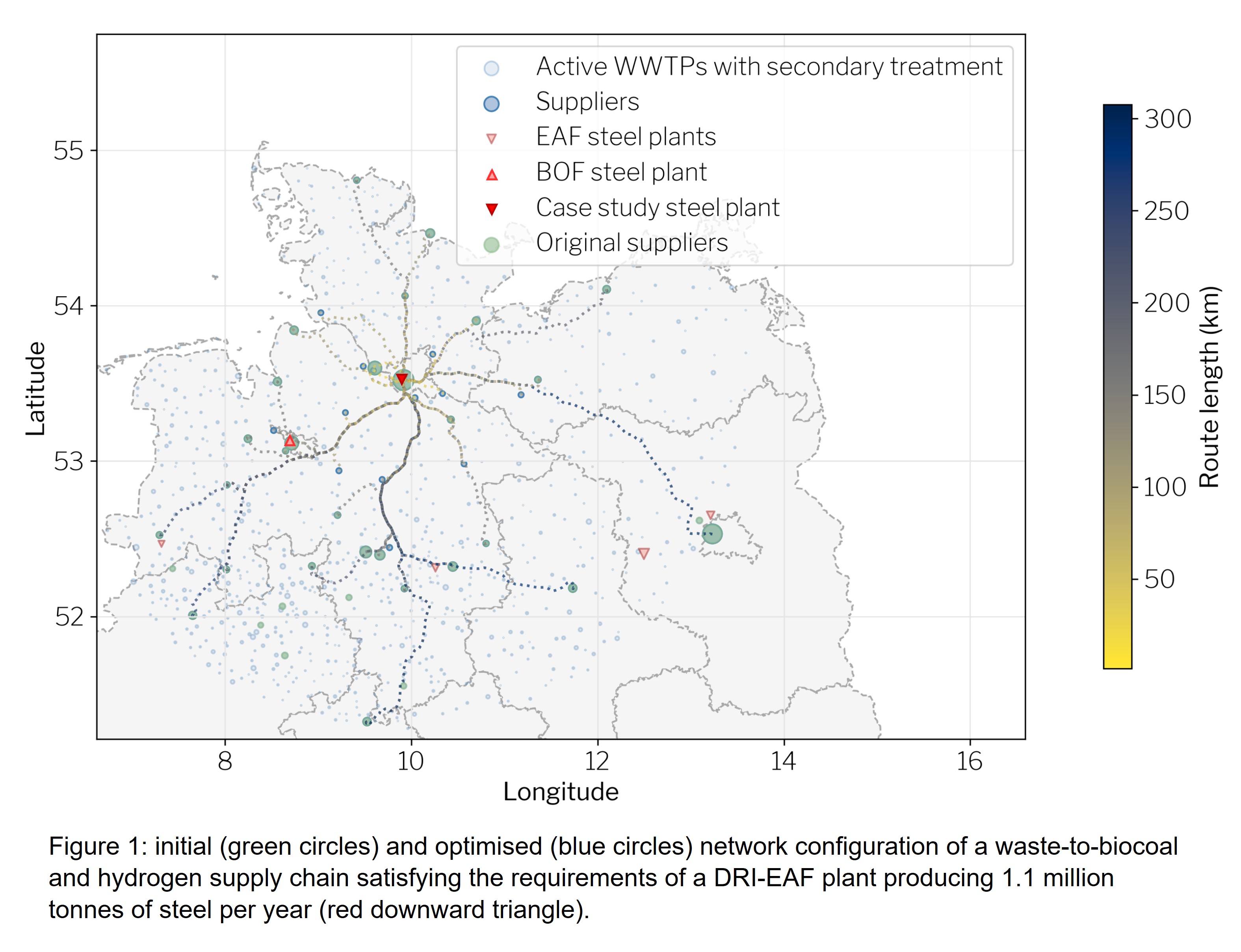

We assessed the feasibility of a waste-to-biocoal and hydrogen process for a DRI-EAF plant located in Hamburg, Germany. To derive a potential supply and value chain for the proposed waste-to-biocoal and hydrogen process, we simulated each WWTP within a 250 km radius of the Hamburg’s DRI-EAF as a biocoal supply node, with a maximum biochar production rate corresponding to their existing dried sludge production capacities. We assumed the sludge pyrolysis units to be on site of the WWTPs, and the biogas cracking to be centralised at the steel manufacturing plant, taking advantage of the natural gas grid for biogas transportation.

Vehicular routes for the transportation of the carbon-based catalyst between each WWTP and the steel plant were calculated through the Open-Source Routing Machine (OSRM) [5], which provides both route distance and approximate travel times. We also modelled alternative waste management strategies for the sludge, including incineration and landfill, to provide a measure of the emissions avoided when the dried sludge is valorised and recycled.

To maximise the impact of the waste-to-biocoal and hydrogen process, we also developed an optimisation model to determine a subset of WWTPs that would provide at least the same amount of biocoal as the initial network whilst reducing transport-related greenhouse gas emissions. It was assumed that each truck transports the catalyst between a single WWTP and the DRI-EAF plant. As such, the number of 42-tonne trucks required for each WWTP - and hence per transport route - was calculated based on the catalyst amount. As the distances between each WWTP and the steel plant were provided as parameters for the optimisation model, distance-based emission factors from the UK Department of Energy Security and Net-Zero (DESNZ), corresponding to an average laden heavy goods vehicle were used [6].

For the optimisation model to calculate the total emissions, a mixed integer linear programme (MILP) was required, where a binary variable was defined to signal if a given WWTP and hence route is active within the optimal solution. A dummy variable was introduced, corresponding to emissions related to each route only if it was active and defined using the BigM method.

Results

Through scaling up process mass balances, we estimated that 133 tonnes of hydrogen are required daily by the DRI-EAF plant with an annual steel production capacity of 1.1 million tonnes when using a hydrogen-only DRI process. The amount of dried sludge provided by the top 35 WWTPs adds up to 450.3 tonnes per day, corresponding to 43% of all dried sludge produced within 250 km of the steel plant and 32 tonnes of methane from the anaerobic digestion.

To produce sufficient hydrogen, we estimated that an additional 530 tonnes per day of methane from outside of the immediate value chain need to be injected in the process. As the number of biomethane plants keeps increasing, currently representing a total installed capacity of 6.4 billion cubic meters of biomethane per year, extracting this amount of methane from the grid per day is however feasible.

This strategy results in a surplus of biocoal produced, which can cover all the carbon requirements of the DRI-EAF plant, as well as 32% of the coal used in neighbouring BF-BOF plants with an annual steel production capacity of 2.6 million tonnes. Sludge pyrolysis also offers emissions-related benefits, avoiding approximately tonnes per day of GHG emissions compared to the incineration and landfill of dried sludge, respectively.

When optimising the selection of WWTPs to reduce transport-related GHG emissions, the optimal solution increased the total number of supplying WWTPs to 41, which produced 451 tonnes of dried sludge per day. The network-wide emissions from the transportation of the carbon-based catalyst were reduced to 5.9 tonnes of GHG emissions per day, a 12% reduction from the initial WTTP selection. This was achieved through selecting WWTPs that had smaller production capacities but were located closer to the DRI-EAF plant instead of the mid-sized WWTPs located further away, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Implications

The conversion of waste sludge to biocoal and hydrogen provides an alternative strategy for producing low-carbon hydrogen in steel manufacturing, thereby reducing reliance on electrolysers and renewable energy capacityin an already energy-intensive industry. And while H-DRI plants are increasingly being viewed as the future of steelmaking [7, 8], the transition period would still heavily rely on existing BF-BOF plants. The valorisation of waste sludge material and production of biocoal could also reduce the emissions from BF-BOF plants during the transition period.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Union - European Innovation Council - H2STEEL project - Grant Agreement 101070741.

References

[1] Ren, Lei, et al. "A review of CO2 emissions reduction technologies and low-carbon development in the iron and steel industry focusing on China." Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews143 (2021): 110846.

[2] Zang, Guiyan, et al. "Cost and life cycle analysis for deep CO2 emissions reduction of steelmaking: Blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace and electric arc furnace technologies." International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control128 (2023): 103958.

[3] Azimi, Arezoo, and Mijndert Van der Spek. "Prospective Life Cycle Assessment Suggests Direct Reduced Iron Is the Most Sustainable Pathway to Net-Zero Steelmaking." Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research7 (2025): 3871-3885.

[4] Salimbeni, Andrea, et al. "Opportunities of integrating slow pyrolysis and chemical leaching for extraction of critical raw materials from sewage sludge." Water6 (2023): 1060.

[5] Open-source routing machine. https://project-osrm.org/ Last accessed: 04/04/2025

[6] UK Department of Energy Security and Net-Zero. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/government-conversion-factors-for-company-reporting Last accessed 04/04/2025

[7] Zang, Guiyan, et al. "Cost and life cycle analysis for deep CO2 emissions reduction for steel making: direct reduced iron technologies." steel research international6 (2023): 2200297.

[8] Graupner, Yannik, Christian Weckenborg, and Thomas S. Spengler. "Effects of European emissions trading on the transformation of primary steelmaking: Assessment of economic and climate impacts in a case study from Germany." Journal of Industrial Ecology6 (2024): 1524-1540.