2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(71a) Rapid Microfluidic Cell Stretching Enables High Throughput Gene Editing of Immune Cells

Authors

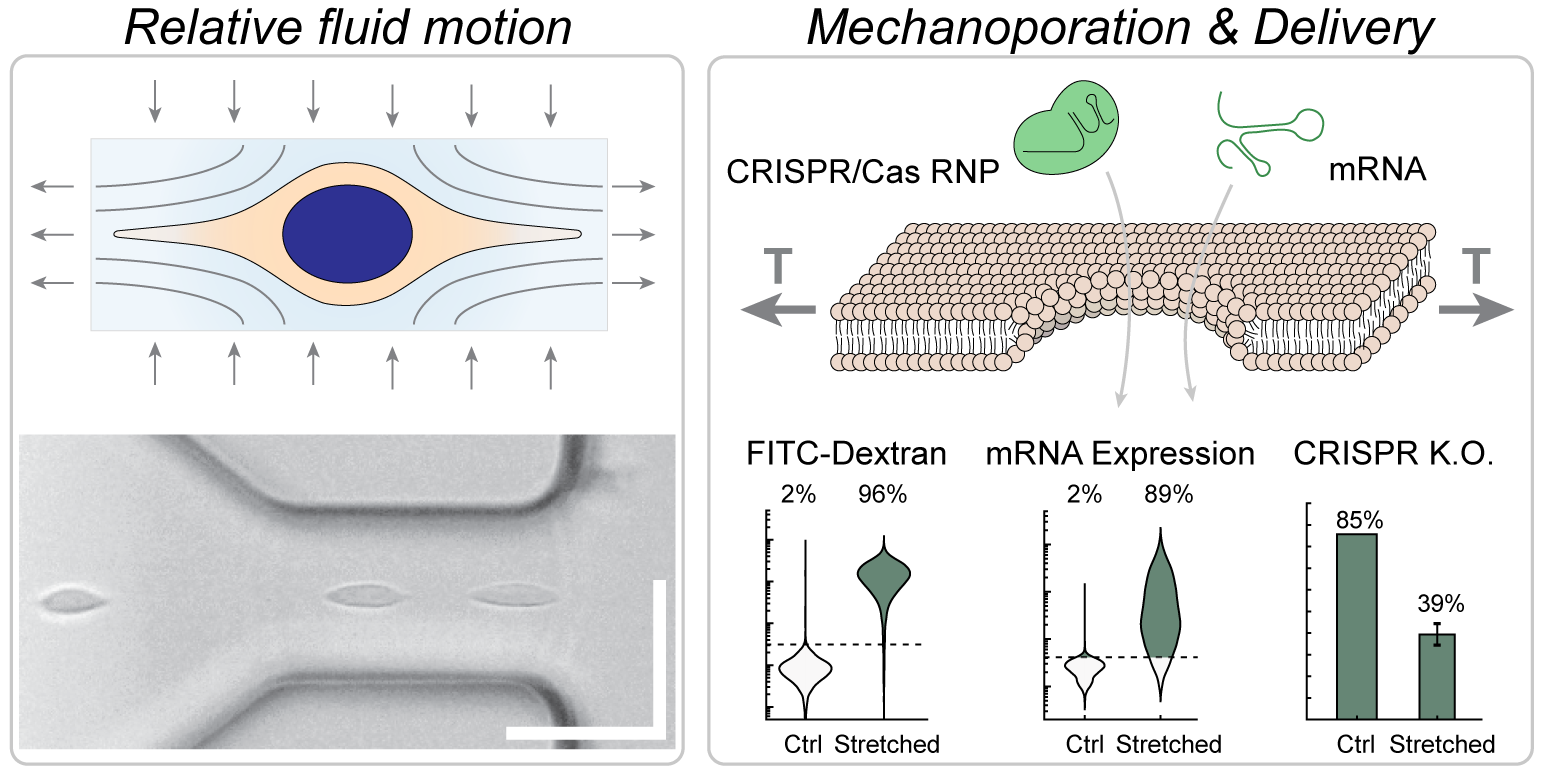

We developed a high-throughput, non-contact method of intracellular delivery which used viscoelastic flow forces within a microfluidic chip to stretch and temporarily permeabilize cells, thereby enabling efficient intracellular delivery of biomolecules such as proteins, nucleic acids, and ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNP) to a range of cell types including Jurkat cells, primary T cells and HEK293T cells. Notably, cell contact with solid surfaces was actively prevented, enabling very fast and scalable transfection at a throughput exceeding 200 million cells per minute.

Intracellular delivery of genetic material and/or gene editing complexes is an essential step in many bioengineering applications in research and medicine. However, viral vectors are unable to target a specific genetic locus, have a limited payload, and can be expensive to manufacture1–3, while synthetic vector systems such as cationic or lipid-based complexes are often inefficient, unstable, and can be cytotoxic4,5. In contrast, direct membrane permeabilization by electroporation (electric fields) or mechanoporation (mechanical tension) can enable efficient delivery, yet scale-up of electroporation for clinical applications has faced challenges associated with nonuniform E-fields, heating, electrolysis, pH changes, electrode corrosion, ionic contamination, and prolonged exposure to low-conductance buffer6, while mechanoporation methods have been nonuniform as well as intrinsically susceptible to clogging due to the use of narrow channels. Therefore, we were interested in investigating whether a contact-free mechanoporation method could be devised, in which the magnitude and duration of membrane tension were uniformly applied to all cells in the sample.

Materials and Methods

Microfluidic devices were fabricated from photolithographic patterns transferred to rigid epoxy and bonded to glass. Cells were suspended in a buffered solution containing the cargo molecule to be delivered as well as 1.5 MDa hyaluronic acid, resulting in a viscoelastic solution. High-aspect ratio curved microchannels were designed to align all cells to the center of the channel. Then, the flow was accelerated by a contraction that was still much wider than the cells (50 microns at the narrowest point). Within the contracting region, cells were stretched in the direction of the flow by relative motion of the surrounding viscoelastic fluid.

Cell deformation was quantified by high-speed microscopy and automated segmentation of cells in the images using a U-Net classifier. Flow kinematics within the device were characterized by particle imaging velocimetry and imaging pathlines. Cell permeabilization and intracellular delivery were quantified by uptake of fluorescent dextrans of different sizes. Cell viability and uptake of dextran were assessed by propidium iodide staining and imaging flow cytometry. Further, quantitative flow cytometry was used to determine the mass of delivered material. The rate at which the pores healed was also assessed by the uptake of dextran several seconds to minutes after processing in the device. Protein and mRNA delivery were assessed using FITC-albumin and eGFP-encoding mRNA respectively. Knockout of the T cell receptor in Jurkat cells was assessed by immunofluorescence two days after CRISPR RNP delivery using the device. Preliminary optimizations for primary T cells and HEK293T cells were also performed using FITC-dextrans.

Results, Conclusions, and Discussions

The channel geometry, delivery solution, and cell recovery conditions were optimized for delivery to Jurkat cells, yielding very efficient intracellular delivery (i.e., 95% of cells) with a total recovery rate of viable and proliferating cells of about 80% at a flow rate of about 2.7 mL/min. Efficient delivery (>85%) was also observed when a different polymer was used, while delivery was low (<40%) at any flow rate for a Newtonian solution without the polymer. Using the optimized protocol, protein and mRNA delivery in Jurkat cells were both very efficient (i.e., ~90% of cells) while RNP knockout of the T cell receptor was moderately efficient (~65% of cells), perhaps due to the need for nuclear delivery for RNP function versus cytosolic delivery for mRNA expression. Delivery performance did not decrease but perhaps slightly increased with increasing cell concentration, up to the highest tested cell concentration of 100 million cells per mL. HEK293T cells could be efficiently transfected (88% of cells) using the device with about 80% cell viability (compared to 85% viability of untreated control cells), if a ‘cytosolic’ (i.e., low sodium, high potassium) delivery solution was used. Primary activated T cells were likewise efficiently transfected (85% of cells) with about 90% of cells viable after 90 minutes.

Altogether, viscoelastic mechanoporation seems to be a feasible approach for efficient and high throughput intracellular delivery of a range of functional biomolecules to a variety of mammalian cell types. This approach should be compared to other recent developments in mechanoporation technologies, especially other microfluidic methods leveraging fluid forces. Cells have been permeabilized by intense flow fields including cross-slot flows7, T junctions8,9, vortices10,11, and nebulizers12. The important differences between viscoelastic mechanoporation and these methods are the process uniformity, throughput, and delivery performance. Viscoelastic mechanoporation was capable of efficient and uniform delivery at a throughput that is much higher than the previous throughput record for mechanoporation, using micro-vortices (a highly nonuniform process that was much less efficient)10,13, and at least two orders of magnitude faster than all other methods. We expect these studies to inspire and enable further development of scalable intracellular delivery strategies.

Acknowledgements

This work was generously supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (K99 AI167063), the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA255602), and the National Science Foundation Engineering Research Center on Advanced Technologies for the Preservation of Biological Systems (#1941543). We are grateful to Carlie Rein for assistance with microdevice fabrication, Shannon Stott for microscopy resources, and Jon Edd, Avanish Mishra, Kaustav Gopinathan, for helpful discussions.

References

- Lee, C. S. et al. Adenovirus-mediated gene delivery: Potential applications for gene and cell-based therapies in the new era of personalized medicine. Genes & Diseases 4, 43–63 (2017).

- Milone, M. C. & O’Doherty, U. Clinical use of lentiviral vectors. Leukemia 32, 1529–1541 (2018).

- Marcucci, K. T. et al. Retroviral and Lentiviral Safety Analysis of Gene-Modified T Cell Products and Infused HIV and Oncology Patients. Molecular Therapy 26, 269–279 (2018).

- Lächelt, U. & Wagner, E. Nucleic Acid Therapeutics Using Polyplexes: A Journey of 50 Years (and Beyond). Chem. Rev. 115, 11043–11078 (2015).

- van der Loo, J. C. M. & Wright, J. F. Progress and challenges in viral vector manufacturing. Human Molecular Genetics 25, R42–R52 (2016).

- Stewart, M. P., Langer, R. & Jensen, K. F. Intracellular Delivery by Membrane Disruption: Mechanisms, Strategies, and Concepts. Chem. Rev. 118, 7409–7531 (2018).

- Kizer, M. E. et al. Hydroporator: a hydrodynamic cell membrane perforator for high-throughput vector-free nanomaterial intracellular delivery and DNA origami biostability evaluation. Lab Chip (2019) doi:10.1039/C9LC00041K.

- Hur, J. et al. Microfluidic Cell Stretching for Highly Effective Gene Delivery into Hard-to-Transfect Primary Cells. ACS Nano (2020) doi:10.1021/acsnano.0c05169.

- Deng, Y. et al. Intracellular Delivery of Nanomaterials via an Inertial Microfluidic Cell Hydroporator. Nano Lett. 18, 2705–2710 (2018).

- Jarrell, J. A. et al. Intracellular delivery of mRNA to human primary T cells with microfluidic vortex shedding. Scientific Reports 9, 3214 (2019).

- Kang, G. et al. Intracellular Nanomaterial Delivery via Spiral Hydroporation. ACS Nano (2020) doi:10.1021/acsnano.9b07930.

- Meacham, J. M., Durvasula, K., Degertekin, F. L. & Fedorov, A. G. Enhanced intracellular delivery via coordinated acoustically driven shear mechanoporation and electrophoretic insertion. Scientific Reports 8, 3727 (2018).

- Jarrell, J. A. et al. Numerical optimization of microfluidic vortex shedding for genome editing T cells with Cas9. Sci Rep 11, 11818 (2021).