2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(327e) Integrating Artificial Neural Networks in Superstructure Optimization for Sustainable Aviation Fuel Production

Authors

Achieving the global target of net zero emissions by 2050 requires the defossilization of air transport. While hydrogen powered aircraft and electrification may be feasible for small-scale or niche applications, large-scale adoption is expected to rely primarily on long-chain liquid sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs) [1].

Determining economically viable pathways for SAF production while ensuring efficient management of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, heat, and electricity presents a significant challenge for engineers. The wide range of possible system configurations adds to this complexity. Potential approaches include biomass-based pathways, CO2 capture combined with water electrolysis for syngas production, and the use of methanol or Fischer-Tropsch (FT) liquids as intermediates, all of which require systematic evaluation. Therefore, a structured methodology is necessary to define material conversions from basic carbon and hydrogen sources while considering electricity and heat requirements.

2. Methodology

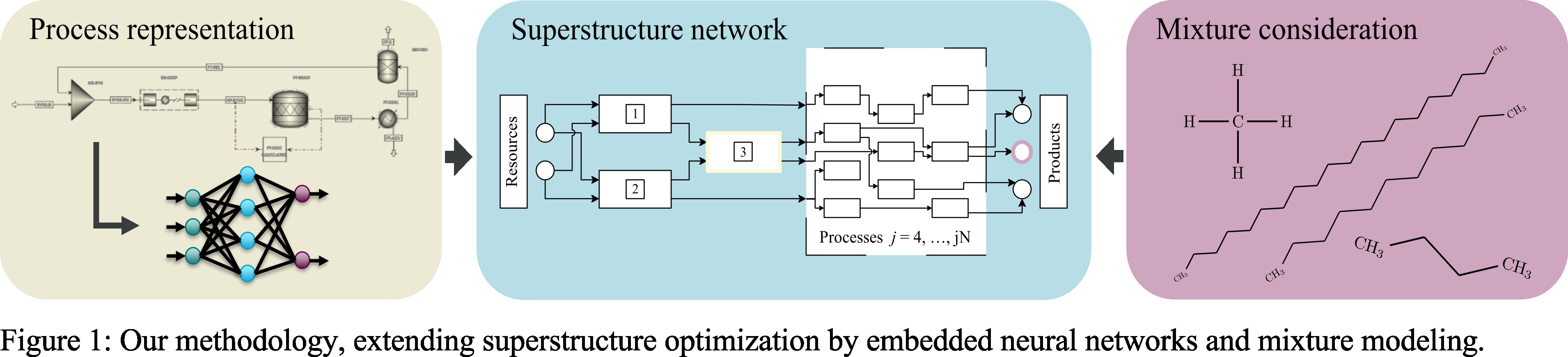

Superstructure optimization in the form of Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) models is frequently used for the design of large-scale chemical production systems. However, conventional approaches consider pure components and neglect material flows of different compositions. In addition, process conditions such as pressure, temperature and composition of the inlet are fixed beforehand and do not represent decision variables of the actual optimization [2, 3]. Since aviation fuels are mixtures of hydrocarbons of different chain length and the composition of syngas is a key variable, we have developed an adapted superstructure optimization formulation that allows for mixture compositions to be represented. The resulting problem is a Mixed-Integer Quadratically Constrained Programming (MIQCP) problem, which can be efficiently solved to global optimality [4]. Further, to overcome conventional linear input-output relationships of individual processes of the network and to increase the degrees of freedom by considering varying process parameters (e.g., temperature, pressure, ...), surrogate models in the form of artificial neural networks (ANNs) are embedded in the superstructure framework. As shown in Figure 1, these ANNs are trained on data generated from Aspen Plus® simulations of the subprocesses, correlating outlet concentrations, electricity, and heat requirements with inlet concentrations and reaction conditions [5]. For the integration of the ANNs, we leverage the Python package OMLT, which facilitates the embedding of machine learning surrogates into Pyomo-based optimization problems [6, 7]. Since we define the ANNs with the ReLU activation function, we can then include them in the optimization problem as mixed-integer linear constraints via a big-M reformulation. Thereby, we can represent highly non-linear dependencies while maintaining a MIQCP formulation [8, 9].

In order to represent the non-linear input-dependent variability of process outputs, ANNs are trained for a biomass gasification, a reverse water-gas shift (RWGS), and a FT process and embedded in the MIQCP [9]. All ANNs are trained with one hidden ReLU layer and 25 to 100 neurons to ensure a proper balance between the precision of the machine learning models and the computational effort required to solve the optimization problem. Using the Aspen Plus®-Python interface, training data is generated from the stationary simulations to train ANNs with 𝑅2 values of 0.999 and higher. For example, the FT ANN enables the calculation of mass fractions in the process outlet of different hydrocarbons, such as n-undecane, as a function of the ANN inputs:

wout,C11H24,FT = fANN,FT(TFT, pFT, win,H2,FT),

where wout,C11H24,FT represents the outlet mass fraction of n-undecane and TFT, pFT characterize the reaction conditions of the FT reactor, while win,H2,FT denotes the inlet concentration of hydrogen into the FT process. With our flexible formulation, we can thus target the desired kerosene hydrocarbon fraction in the FT output by optimizing within the constraints of the required physical properties. Modeling the hydrocarbons of different chain length and structure as components of our superstructure provides more detailed information about the SAF composition depending on the process route and feedstocks.

3. Results and discussion

As objective function of the optimization, we consider the sum of investment and operating cost per kilogram of kerosene (C8-C16 hydrocarbons). Using the 𝜀-constraint method, Pareto optimal solutions with specified CO2 emissions for kerosene production are generated.

Without restricting CO2 emissions, plant design is based on an autothermal reforming process, resulting in a cost of 0.79 $/kgkerosene as reference value, which is in good agreement with literature values. When CO2 emissions are constrained, kerosene production becomes more expensive, as biomass replaces natural gas as the source for C and H. We generate plant designs with specific kerosene costs of up to 3.52 $/kgkerosene and specific CO2 emissions far below the net zero limit at -2.22 kgCO2/kgkerosene. Negative CO2 emissions are achieved via the carbon uptake of the biomass in combination with direct air capture and carbon sequestration. CO2 is captured from the air and stored, leading to low emissions in connection with kerosene production, at the expense of higher production cost. We observe that cost-optimal systems are based on biogenic carbon rather than atmospheric carbon for the fuel synthesis, with DAC providing additional negative emissions to adhere to the emissions constraint. Atmospheric CO2 is only used for the synthesis when biomass availability is limited; such designs are associated with kerosene costs of at least 4 $/kgkerosene.

By embedding the ANNs, additional degrees of freedom at plant and process unit level, such as reaction temperature and pressure, are also optimized as decision variables. Depending on parameters such as electricity price, optimal operating modes for the subprocesses are obtained, leading to designs with lower specific cost for the kerosene production. Comparisons with results from classical superstructure approaches, where we fix the decision variables at the lower levels (temperature, pressure, input composition), indicate that by considering additional degrees of freedom, production costs can be lowered by up to 20%.

4. Conclusions

Our work highlights the need for the consideration of mixture compositions when optimizing SAF production pathways. It presents a novel optimization framework using MIQCP with embedded ANNs to model complex chemical conversion processes. By incorporating ANNs, we simultaneously optimize the system topology, operating conditions of the subprocesses, and mixture compositions. The results show that while the biomass based pathways offer the most economically viable sustainable solutions, achieving net zero CO2 emissions leads to a cost increase of almost three times compared to the fossil reference design. The study demonstrates that optimizing additional process parameters (in particular inlet compositions, pressure and temperature) can reduce specific kerosene production cost by up to 20% compared to conventional approaches, offering valuable insights for sustainable aviation fuel development.

References

[1] Freire Ordóñez, D.; Halfdanarson, T.; Ganzer, C.; Shah, N.; Mac Dowell, N.; Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Evaluation of the potential use of e-fuels in the European aviation sector: a comprehensive economic and environmental assessment including externalities. Sustainable Energy & Fuels, 2022, 6, 4749–4764.

[2] Ganzer, C.; Mac Dowell, N. A comparative assessment framework for sustainable production of fuels and chemicals explicitly accounting for intermittency. Sustainable Energy & Fuels, 2020, 4, 3888–3903.

[3] Gonzalez-Garay, A.; Heuberger-Austin, C.; Fu, X.; Klokkenburg, M.; Zhang, D.; van der Made, A.; Shah, N. Unravelling the potential of sustainable aviation fuels to decarbonise the aviation sector. Energy Environ. Sci., 2022, 15, 3291–3309.

[4] Gurobi Optimization. The Leader in Decision Intelligence Technology - Gurobi Optimization. https://www.gurobi.com/ (Accessed March 28, 2025).

[5] Aspen Technology Inc. Aspen Plus. https://www.aspentech.com/en/products/engineering/aspenplus (Accessed March 28, 2025).

[6] Bynum, M.L.; Hackebeil, G.A.; Hart, W.E.; Laird, C.D.; Nicholson, B.L.; Siirola, J.D.; Watson, J.-P.; Woodruff, D.L. Pyomo - optimization modeling in Python. Third Edition Vol. 67. Springer, 2021.

[7] Ceccon, F.; Jalving, J.; Haddad, J.; Thebelt, A.; Tsay, C.; Laird, C.D.; Misener, R. OMLT: Optimization & Machine Learning Toolkit. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 2022, Volume 23, 1–8.

[8] Plate, C.; Hahn, M.; Klimek, A.; Ganzer, C.; Sundmacher, K.; Sager, S. An analysis of optimization problems involving ReLU neural networks. 2025. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.03016.

[9] Grimstad, B.; Andersson, H. ReLU networks as surrogate models in mixed-integer linear programs. Computers & Chemical Engineering, 2019, 131, 106580.