2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(183p) Exploring the Impact of Cell-Cell Junction Strength on Spheroid Stiffness Using Extensional Flow Microfluidic Device

Authors

Mechanical properties of cells have garnered increasing attention in recent years. These properties, particularly resistance to deformation (stiffness), reflect the structure of a cell’s subcellular components. Previous research has demonstrated that mechanical properties are essential for understanding cellular phenomena, complementing biochemical insights [1]. In many biomedical contexts, such as cancer, researchers often study not individual cells but cell aggregates [2]. Consequently, understanding the biomechanics of these aggregates is critical. The significance of this fundamental knowledge is in developing more effective treatments and diagnostic methods by elucidating the underlying behavior of cells and their aggregates. Moreover, it plays a vital role in tissue engineering, where biomaterials containing cells and extracellular matrix (ECM) are employed for wound healing or tissue regeneration [3]. Since cell clusters represent a simpler structural unit of tissue, studying their biomechanics can serve as a fundamental starting point for such analyses.

Cell aggregates are significantly more likely to cause metastasis than single cells, making them a major contributor to cancer-related mortality [4]. It was previously doubted that cancer cell aggregates could contribute to metastasis, as they were thought to be unable to pass through capillary blood vessels. However, research by Au et al. demonstrated that circulating tumor cell aggregates can deform into single-file chains to navigate through capillary channels and retain their shape after exiting [5]. This finding highlights the intriguing mechanical properties of cell aggregates, needing further investigation.

Cell spheroid biomechanics has been studied using many of the same techniques used for single cell biomechanics. This includes bulk techniques that deform the whole spheroid (e.g., parallel-plat compression), localized techniques that contact a small area (e.g., AFM), and interior perturbations (e.g., cavitation) [2]. From these studies, we know that the mechanical behavior of spheroids is determined by the interaction of intercellular junctions, cell contractility, and the ECM, with some mechanical models proposed [6].

In this work, we explore the impact of cell-cell junction strength on spheroid stiffness. As far as we know, the extent to which this factor affects spheroid stiffness is underexplored. We investigate the deformation of spheroids from two groups of the same size: one group suspended in a solution without calcium, and the other suspended in a solution with calcium. We measured their deformation using an extensional flow microfluidic device.

METHODS

PANC-1 pancreatic cells (ATCC) were used to fabricate spheroids (~100 μm diameter). Spheroids were fabricated using 3D Petri Dish micro-molds (Microtissues, Inc.). These micro-molds contain 256 microwells into which molten agarose solution is poured and cooled. A cell suspension containing 3,840 cells in 120 μL of media was added to the agarose micro-molds and incubated for four days to form spheroids with average diameter of 100 μm. Matrigel was added to the media to form an extracellular matrix (ECM) around the spheroids.

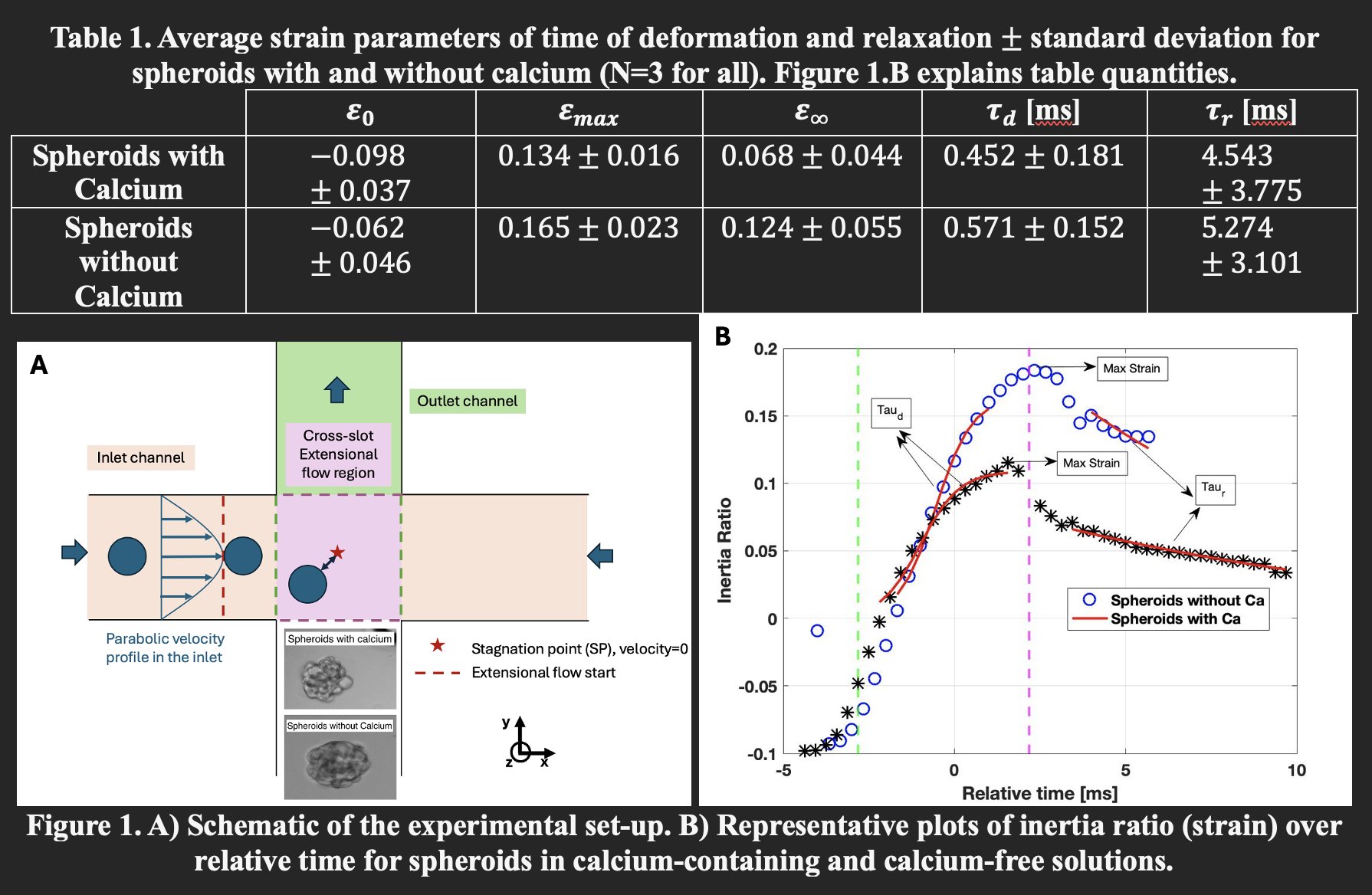

Stretching experiments were conducted in a microfluidic extensional flow device, commonly called a cross-slot, which consists of two perpendicular channels intersecting at 90 degrees to generate a linear extensional flow field (Figure 1.A). For spheroids, a cross-slot with channel width of 300 μm and depth of 270 μm was used. Spheroids were suspended in two different solutions: one group in an aqueous 0.8% w/v methyl cellulose solution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing calcium, and the other group in the same solution, but without calcium in the PBS. The viscosity of both solutions was approximately 90 mPa.s. Spheroids were stretched at an extensional strain rate of 690 s⁻¹.

Videos of spheroids were recorded as they entered the straight inlet channel (Poiseuille flow) and stretched in the central extensional flow region and exited the straight outlet channel. Imaging was performed using brightfield microscopy at 10× magnification (Zeiss Axiovert 200M) and a high-speed camera (KAYA Instruments JetCam, 3,000 fps). Image processing was conducted in MATLAB (MathWorks). Strain (deformation) was calculated using inertia ratio from the second moments of areas:

In previous studies [7], cell strain was computed using the long and short axes of the best fitted ellipse. However, this method is unreliable for irregularly shaped spheroids. The inertia ratio provides a more robust measure of shape deformation, as it quantifies mass distribution in space. For this study, the deformations of three representative spheroids with calcium and three representative spheroids without calcium were analyzed and compared.

RESULTS & DISCUSSION

To compare the mechanical responses time of the two groups: spheroids suspended in solution with calcium and those without, we plotted inertia ratio (representing strain) over time. Figure 1.B presents a representative plot for each group.

We quantified several strain metrics: initial strain, maximum strain, and final strain. Here, initial strain refers to the inertia ratio of spheroids in the inlet channel before entering the extensional flow region. Maximum strain is defined as the peak inertia ratio observed within the extensional flow region, where the extensional strain rate is constant. Final strain is the average inertia ratio measured in the straight outlet channel, where spheroid exited the extensional flow region. Additionally, we calculated the deformation time (τ_d) and relaxation time (τ_r) by fitting an exponential curve to the strain versus time data.

Table 1 summarizes the average values of parameters mentioned above for PANC-1 spheroids with and without calcium. Each group’s data represents the average of three spheroids. The average diameter of spheroids in the calcium group was 137 ± 10 μm, while those in the calcium-free group averaged 115 ± 10 μm.

The results indicate that spheroids in calcium-containing solutions are stiffer and undergo less deformation in the extensional flow region compared to those in calcium-free solutions. Although initial strain values were similar across groups, the maximum strain was significantly lower for the calcium group. Similarly, the final strain was reduced in spheroids suspended in calcium.

The deformation time (τ_d) was longer for spheroids without calcium, suggesting that spheroids in the calcium group deform more quickly. A similar trend was observed for relaxation time (τ_r), where spheroids lacking calcium took longer to relax and reach their final strain in the outlet channel. Together, these findings support the conclusion that calcium enhances cell-cell adhesion, resulting in stiffer spheroids with distinct mechanical responses under extensional flow.

CONCLUSIONS

The spheroids analyzed in this study were approximately the same size, allowing for a more controlled comparison of the effect of calcium on spheroid stiffness. As spheroids grow, the number of cell-cell interactions increases, potentially altering their mechanical properties. By using spheroids of similar size, we minimized this variable to focus on the influence of calcium-mediated cell-cell junctions.

Although only a small number of spheroids were tested in each group (three with calcium and three without), the preliminary results are promising. Spheroids suspended in methylcellulose in PBS without calcium exhibited significantly greater deformation compared to those in PBS with calcium. This suggests that the presence of calcium strengthens cell-cell junctions, resulting in stiffer spheroids.

These findings align with previous studies that demonstrate the critical role of cell-cell junctions in determining spheroid stiffness [8]. By depriving spheroids of calcium or supplementing them with it, we aimed to modulate the strength of these junctions and investigate the corresponding effects on biomechanical behavior.

In future work, we plan to repeat the experiment using a larger sample size, at least 50 spheroids per group, while maintaining consistent spheroid sizes. We will quantify strain, deformation time (τ_d), and relaxation time (τ_r) to provide statistically robust conclusions. Additionally, we will perform immunofluorescent staining for key cell-cell junction proteins such as E-cadherin, β-catenin, and ZO-1 to verify changes in junction integrity. These proteins are central to adherens and tight junctions in tissue architecture. Understanding which proteins are most affected by calcium deprivation will help establish a link between mechanical behavior and the molecular biology of cancer spheroids. Bridging these domains is essential for gaining deeper insight into tumor mechanics and could inform future strategies for cancer diagnosis or treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This is supported by the National Science Foundation (CMMI Award No. 2301804). Thank you to Dr. Shakir Khan (University of Massachusetts Boston) for guidance in cell culture.

REFERENCES

[1] Urbanska, M., & Guck, J. (2024). Annual Review of Biophysics, 53(1), 367–395.

[2] Boot, R. C., Koenderink, G. H., & Boukany, P. E. (2021). Advances in Physics: X, 6(1), 1978316.

[3] Guimarães, C. F., et al. (2020). Nature Reviews Materials, 5(5), 351–370.

[4] Cheung, K. J., & Ewald, A. J. (2016). Science (New York, N.Y.), 352(6282), 167–169.

[5] Au, S. H., et al. (2016). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(18), 4947–4952.

[6] Efremov, Y. M., et al. (2021). Biophysical Reviews, 13(4), 541–561.

[7] Guillou, L., et al. (2016). Biophysical Journal, 111(9), 2039–2050.

[8] Schuhmacher, D., Sontag, J.-M., & Sontag, E. (2019). Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 7, 30.