2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(159b) Economics, sociotypes and risk aversion as hurdles for biobased feedstock adoption

Crude oil is a complex mixture of hydrocarbons with sulfur compounds and metals. As the world depletes light sweet crude, refineries must adapt their operations to treat heavier crude requiring more complex processing. Biomass (lignocellulosic, table waste) and plastics are at least as complex as crude oil. The inherent low feedstock cost of waste addresses the economic criteria of lower operating cost. However, because of the complexity meeting the first criteria of lower capital costs is problematic. Furthermore, biomass conversion to low value fuels (pyrolysis oils, torrefied wood, syngas for methanol or synthetic crude) is economically challenging. Maintaining the carbon-carbon and carbon-oxygen functionality to produce value added specialty chemicals and monomers would be more economic but the success of this avenue remains somewhat elusive.

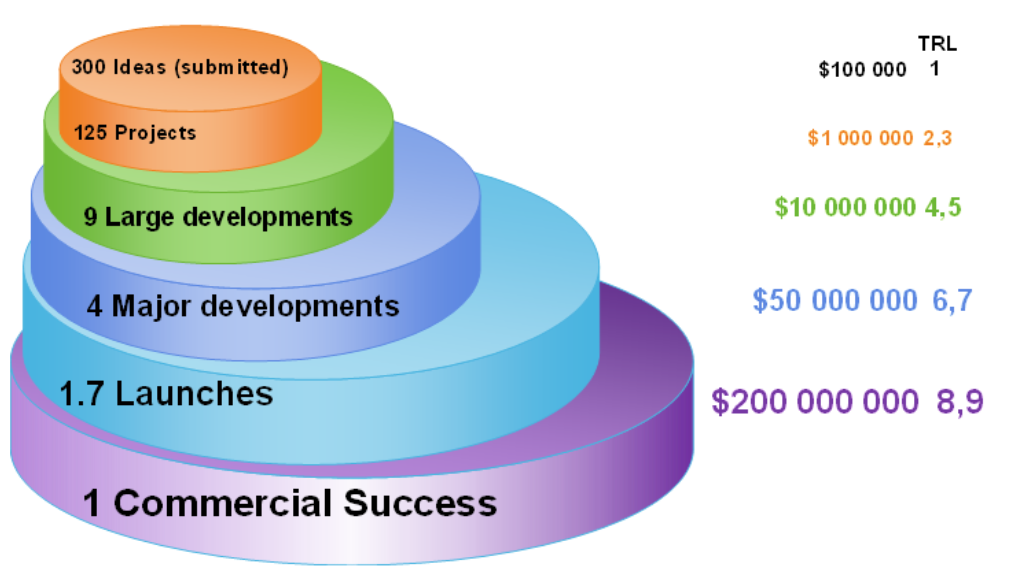

Developing new processes is as uncertain as projecting its cost. To achieve 1 commercial success, DuPont considered that it started with thousands of ideas. From these ideas, 300 would be submitted to management to flush out their potential. Scouting costs for this step would be on the order of $100 – 200,000 to run a couple of tests. Only 1/3 of the ideas would advance to the project phase costs of $1,000,000 and <2 y of research.

Of these 125 projects less than 10% proceed to the large development stage: up to $10 million of research, a dozen or so chemists, engineers, technicians and operators for a pilot plant. Approximately 50% of these would lead to major developments with as much as $50 million of investment including a demonstration unit. Less than half of these would launch into the market and then one out of 1.7 launches would be a commercial success with a cost of let's say $200 million.

Companies adopt strategies to derisk the development phase and to kill projects that have a low probability of success. Stage-gate analyses, for example, include manufacturing personnel, business leaders, and researchers to ensure that the project recognizes obstacles and set predetermined milestones with Go/No Go/Redirect recommendations. These programs attempt to accelerate the commercializing process – concept (Technology Readiness Level 1 - TRL1), evaluate (TRL2,3) , optimize (TRL4), pilot (TRL5,6), design (TRL7), start-up (TRL8), commercialize (TRL9) – from >15 year to < 5 y. Despite these programs, only one in four major developments succeeds and the <5 y time frame is unrealistic, although that might be the time the management will remain in position.... Tracking technology readiness with the TRL designation is accompanied by Manufacturing Readiness (MRL) and an Operation Readiness Checklist (ORC). Many of the timelines for these tracking metrics are completed in parallel. Delays in progression of any of will impact the time-line.

New technology development involving catalysts requires an independent metric/timeline for the process as well as for catalyst manufacture. For the process, the scope of the challenges that are considered during the manufacturing stage include mechanical issues (corrosion, erosion, scale, compressors, material of construction), operation (control, safety, start-up, controlled shut down, interlock shut down, analytical), and design (pressure drop, heat transfer, flow patterns, contact efficiency, gas/solids injection distribution, inventory), inlet gas composition (potential for deflagration, coking, scale) [1]. With respect to the catalyst, the issues are related to yield in synthesis (cost), activation, chemical and thermal stability, attrition resistance, kinetics (selectivity, byproducts, weight hour space velocity, and temperature) [2]. At each development stage (experimental, pilot, commercial) researchers address unknowns but as the scale increases other factors emerge. The commissioning/start-up phase can last several years in which the full cost of financing and operation accumulate with only a partial offset of cash from operations.

Project economics are necessary but insufficient to succeed. A champion within the organization is required and support from the business, research and operations. It is also important that the scope of the project remains constant through the years. The sociotypes related to technology developed within a corporation starts with innovators and early adopters (>TRL6) that create a vision of the future [23]. As the development proceeds through the TRLs, it faces resistance from pragmatists who prefer to still with the herd ( TRL7) and conservatives who resist change. As the project proceeds through TL8-9, laggards and skeptics emerge, and when these individuals have budget responsibility, commercialization is unlikely.

It is not uncommon that the level of precision on conversion, yield or selectivity requested from the researchers is at <+/- 10.1 %, to identify a list of equipment, with which cost estimators will initially give a Capex at Class 5 level of +/- 50 %, while the business would have no precise idea of the product market value nor commitments/contract on the feedstock costs. It is important to investigate more options in the research phase, and spend more money there, in order to have more options at the piloting phase. Hurdles on feedstock substitution for a specialty chemical require hundreds of millions of dollars in investment and champions within management but even then, laggards and skeptics kill projects. For bulk chemicals – hydrogen, methanol, ethanol, (bio)diesel, transportation fuel, NH3, acetic acid, ethylene – the markets are large, but the market value is low and so to maximize profit margins, plants have to be enormous (>500 kt/y) to achieve economies of scale. The learning curve helps reduce investment on the nth plant [4] but businesses are unwilling to assume this risk especially the feedstock for these plants are widely distributed that increases transportation and other logistical costs. So, it is unlikely that industry alone will adopt biofeedstocks; they will require subsidies and mandates/legislation to make it possible. Even then business are skeptical about legislators who are susceptible to macro events and could change incentives at any time.

[1] Patience GS, Chaouki J. 7 Case study II: n-Butane partial oxidation to maleic anhydride: commercial design. In: Chaouki J, Sotudeh-Gharebagh R (ed.) Scale-Up Processes: Iterative Methods for the Chemical, Mineral and Biological Industries. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter; 2021. p.167-190. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110713985-007

[2] Patience GS. 6 Case study I: n-Butane partial oxidation to maleic anhydride: VPP manufacture. In: Chaouki J, Sotudeh-Gharebagh R (ed.) Scale-Up Processes: Iterative Methods for the Chemical, Mineral and Biological Industries. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter; 2021. p.147-166. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110713985-006

[3] Darabi Mahboub, MJ, Xu, J, Patience, GS, Dubois, JL. "1 Conversion of glycerol to acrylic acid". Industrial Green Chemistry, edited by Serge Kaliaguine and Jean-Luc Dubois, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2025, pp. 1-39. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111383446-001.

[4] Patience GS, Boffito DC. Distributed production: Scale-up vs experience. Journal of Advanced Manufacturing and Processing. 2020; 2:e10039. https://doi.org/10.1002/amp2.10039.