2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(288d) DNA-Guided, on-Membrane Assembly of Conjugated Polymer Nanoparticles for Enhanced Detection of Cell Surface Markers

Introduction

Cell surface markers are proteins that are expressed on cell membrane. They have been reported to be associated with diseases such as cancer. Therefore, they have been targets for diagnosis and therapy. Flow cytometry (FCM) is a gold standard to detect these markers through antibody-based fluorescent labeling. Although more than several thousand markers need to be expressed on a cell for reliable detection, some crucial markers do not meet this detection limit. Therefore, strategies to enhance the fluorescence signal per marker molecule are highly sought after. To amplify fluorescence signals, in previous studies, antibody was modified with multiple fluorescent dyes. However, excessive modification made antibodies lose their binding ability. On the other hand, the use of large fluorescent particles (Ca. >60 nm) with high brightness tends to inhibit access to neighboring makers due to steric hindrance. Therefore, an alternative strategy for fluorescence amplification for antibodies is needed.

On the other hand, DNA-mediated nanoparticle assembly technology has attracted attention recently. Nanoparticles with single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) modified on their surface are assembled by hybridization with linker DNA having complementary regions to form higher-order conformation. Since the properties of photo-functional nanoparticles such as gold nanoparticles and quantum dots change with steric configuration, such as the inter-particle distance, their assembly can be expected to expand their functions [1]. Therefore, in this study, we used this technology to assemble fluorescent nanoparticles on cell surface markers via DNA hybridization. The idea was to increase the brightness per marker while maintaining the binding ability of antibodies.

Conjugated polymer nanoparticles (Pdots) were employed as fluorescent nanoparticles for signal amplification in FCM application. Pdots are one of the new fluorescent probes [2]. Pdots have been investigated in the biomedical field because of their highly bright fluorescence, excellent biocompatibility, photostability, and size-tunability [3].

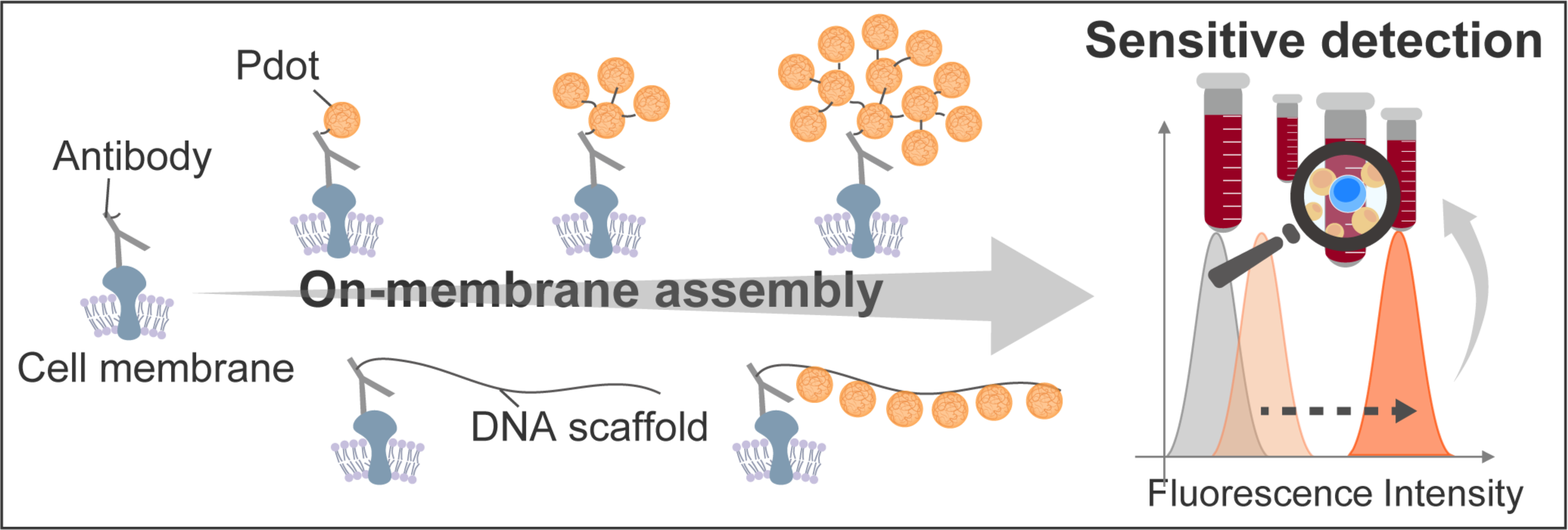

In this study, we developed a technique for fluorescence enhancement without reducing the binding capacity of antibodies by DNA-guided on-membrane Pdot assembly, with the aim of detecting cell surface markers with high sensitivity (Fig. 1).

Experimental

1 .Synthesis of Pdots

Pdots was synthesized by nanoprecipitation method previously reported by our group [3]. Poly [2-methoxy-5-(2-ethylhexyloxy)-1,4-phenylenevinylene] (MEH-PPV) and poly (styrene-co-maleic anhydride) (PSMA) were used as fluorescent conjugated polymer and dispersion stabilizer, respectably. The mixture of MEH-PPV (0.04 mg/mL) and PSMA (0.01 mg/mL) dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF) was added to 100 mL of pure water under sonication and vigorous stirring to form a homogenous Pdots solution. After purification by ultracentrifugation, the particle size distribution and morphology were evaluated by DLS and TEM observation.

2. DNA modified Pdots (DNA-Pdots)

The Pdot surface were modified with DNA by carbodiimide reaction. Amine-functionalized single-stranded DNAs, 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and N-hydroxy succinyl imide (NHS) were added to the Pdots dispersion for the reaction. After centrifugation to remove free DNA, surface evaluation was conducted by FT-IR.

3. Study of Pdot assembly on cells

CD19 expressed on Nalm-6, a cell line derived from human B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells, was used as a target for demonstrating Pdot assembly on cell membrane. To assemble Pdot on membrane, we tried two strategies; one is a DNA-mediated sequential assembly of Pdot, and the other is a one-pot polymerization of Pdot-conjugated DNA chain. The fluorescence intensity of each was evaluated by confocal laser microscope and FCM.

Results and Discussion

1. Synthesis of Pdots

TEM image revealed that the obtained nanoparticles have an average diameter of 22 nm. Absorption and fluorescence spectrum of the obtained MEH-PPV Pdots were also evaluated by UV-vis spectroscopy and fluorometer. Pdots exhibit broad absorption band ranging from 400 nm to 550 nm, which is convenient for fluorescence microscopy and laser excitation. The maximum fluorescence emission peak was 590 nm, which is longer than autofluorescence of cells. These results illustrated the proper optical property of Pdots for surface marker detection.

2. DNA modified Pdots (DNA-Pdots)

FT-IR spectra of free DNA and Pdots before and after DNA modification were measured. Spectrum of DNA-Pdots had peaks at 1090 cm-1 and 1200 cm-1 derived from the phosphate group of DNA, and the peak at 3400 cm-1 derived from the amide bond. Therefore, successful DNA modification on the surface of Pdots was suggested.

3. Study of Pdot assembly on cells

To evaluate the feasibility of Pdot assembly on actual cell surface markers, CD 19 expressed on Nalm-6 cells was chosen as the target. Confocal laser microscope was used for obtaining fluorescence image of Pdot assembly on membrane at each step. Fluorescence intensity was weak at the one-step labeling, whereas the increase in brightness with assembly was confirmed, indicating successful assembly of Pdots on the cell surface marker. Further fluorescence evaluation was conducted using FCM. The fluorescence intensity distribution shifted toward higher brightness as the number of assembly steps increased. Notably, the two-step sequential assembly of Pdots enhanced fluorescence intensity by 36-fold compared to the one-step labeling of Pdots on antibodies. Additionally, this two-step assembly resulted in a 125-fold amplification of the fluorescence signal from CD19 on Nalm-6 compared to conventional fluorescent dye-based labeling methods.

Moreover, the sequential assembly of 22 nm Pdots was 24-fold brighter than one-step labeling with 81 nm Pdots, despite the latter having a similar total volume to the assembled 22 nm Pdots. It would be due to the steric hindrance between large particles, which limits labeling efficiency. These results further highlighted the usefulness of the proposed sequential assembly strategy of Pdots mediated by DNA[4].

While the sequential assembly strategy successfully achieved high brightness, its complex and lengthy process motivated us to explore an alternative approach. To simplify the process, we employed hairpin DNA to induce on-membrane hybridization chain reaction (HCR) for Pdot assembly. HCR involves two species of hairpin DNA that remain kinetically trapped in the absence of an initiator [5]. When a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) initiator binds to one hairpin, it triggers a cascading series of hybridization events, leading to the formation of long double-stranded DNA chains. To assess the feasibility of HCR-mediated Pdot assembly, we prepared the reaction system for CD19 labeling and compared conditions with and without hairpin DNA via confocal laser microscope. Fluorescence from Pdots was observed only in the presence of hairpin DNA, whereas no signal was detected without it. These results suggest that HCR successfully proceeded on the cell membrane to generate a DNA scaffold, to which Pdots were conjugated.

Summary

Pdots and antibodies were modified with single stranded DNAs. After sequential assembly of Pdots on cell membranes via complementary DNA linkers, the fluorescence signal in FCM was successfully amplified, giving much stronger signal than conventional fluorescent dye. By sequential assembly of Pdots, fluorescence intensity can be enhanced while avoiding steric hindrance between large particles. Furthermore, we developed an HCR-driven on-membrane Pdot assembly strategy for simplified fluorescence signal enhancement. By leveraging Pdot assembly via HCR, we aim to amplify fluorescence signals while preserving the specificity of antibody-based labeling. These approaches are expected to provide a robust and practical solution for the high-sensitivity detection of low-abundance cell surface markers, potentially advancing biomarker-based diagnostics and research in immunology, oncology, and stem cell biology.

References

[1] S. Ohta, D. Glancy, W.C.W. Chan, Science, 351, 841-845, (2016).

[2] C. Wu, J. McNeill, ACS Nano, 2, 11,2415-2423, (2008).

[3] N. Nakamura, N. Tanaka, S. Ohta, RSC Adv., 12, 11606-11611, (2022).

[4] Y. Maeda, N. Nakamura, S. Ohta, Adv. Funt. Mater., 2315160, (2024).

[5] R. M. Dirks, N. A. Pierce, PNAS, 101, 43, 11,15275-15278, (2004).