2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(21i) Comparative Analysis of Living Vs. Non-Living Indigenous Microalgae for Mercury Bioremediation: Mechanisms, Kinetics, and Applications

Authors

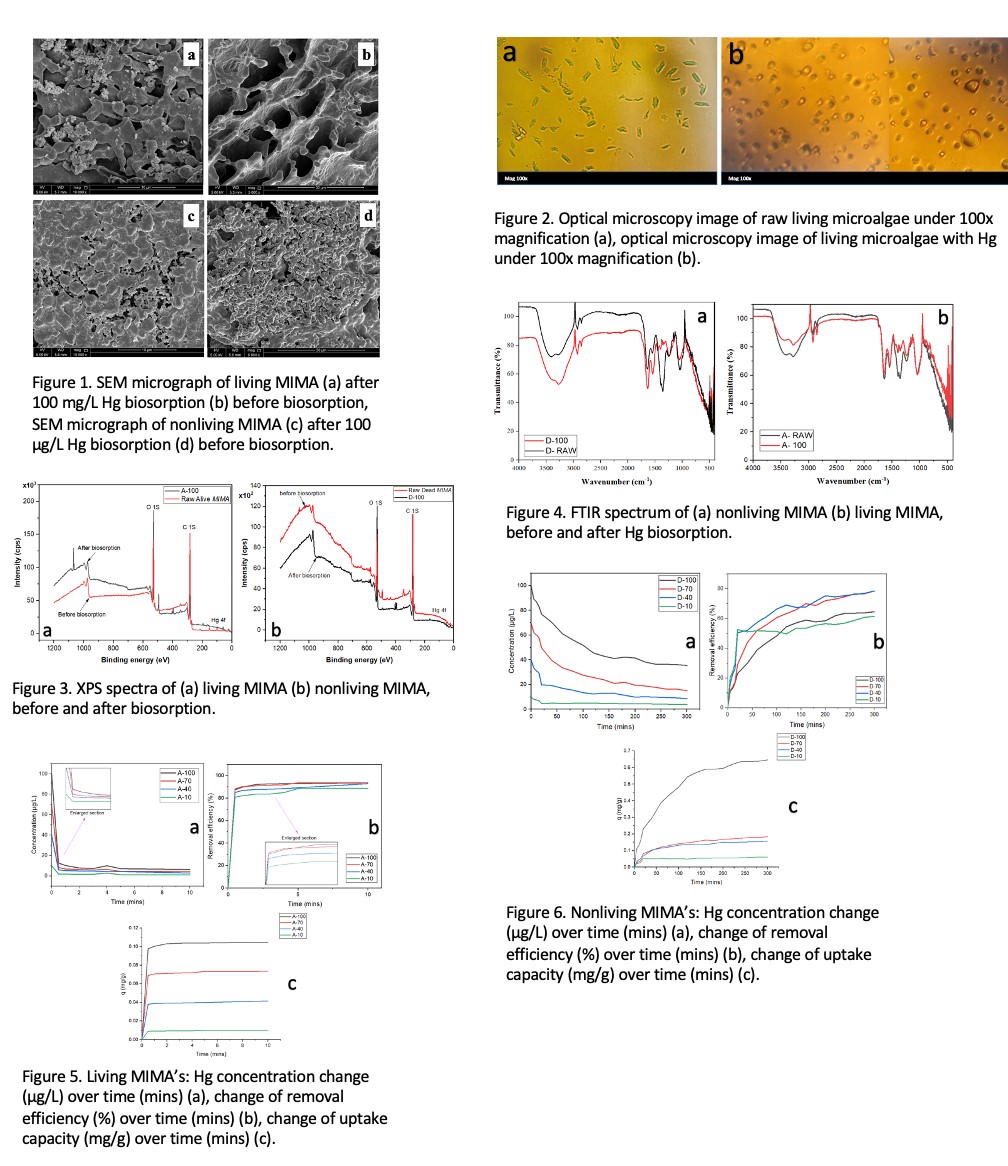

Initial screening experiments were crucial in establishing the upper concentration limits for viable mercury removal. At 200 μg/L, the initially vibrant green microalgal culture maintained its vitality for two days before showing signs of stress, manifested as browning of the culture. At higher concentrations (300-500 μg/L), severe toxicity was observed within the first 24 hours, indicated by rapid browning of the culture and cell death. These observations were instrumental in establishing 100 μg/L as the upper limit for sustainable mercury removal in our experiments. Surface morphology and binding mechanisms were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), optical microscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR).

Living microalgae demonstrated exceptional mercury removal efficiency (89-94%) with remarkably rapid kinetics, achieving equilibrium within 2 minutes across all tested concentrations as shown in Figure 5b. This rapid removal is attributed to a unique surface-based binding mechanism, evidenced by optical microscopy observations showing immediate formation of distinct boundary layers around cells upon mercury exposure as illustrated in Figure 2b. Isotherm studies revealed that the Dubinin-Radushkevich model best described the biosorption process (R² > 0.990), with a mean free energy value of 5 kJ/mol indicating predominantly physical adsorption. Kinetic analyses showed excellent correlation with the pseudo-second-order model (R² > 0.996), suggesting that while initial binding is physical, subsequent chemical interactions may occur. The remarkably high rate constants (216-767 g/mg·min) explain the rapid equilibrium achievement. In contrast, non-living biomass exhibited distinctly different characteristics, with slower kinetics requiring 200-250 minutes to reach equilibrium but achieving higher absolute uptake capacities (maximum 0.72 mg/g at 100 μg/L) as shown in Figure 6c. The removal efficiency ranged from 61.5% to 79% across the concentration spectrum as presented in Figure 6b. The biosorption mechanism was best described by the Freundlich isotherm (R² = 0.964), indicating heterogeneous surface binding, followed by Dubinin-Radushkevich (R² = 0.946). Kinetic analyses showed superior fitting with the pseudo-second-order model, though with significantly lower rate constants (0.024-1.055 g/mg·min) compared to living systems. Multi-stage uptake patterns in non-living biomass suggested complex mass transfer processes involving surface adsorption followed by intraparticle diffusion.

As presented in Figure 3, XPS analysis confirmed mercury binding at the cellular surface for both systems, with significant changes in C 1s and O 1s spectra indicating direct mercury-oxygen coordination. FTIR spectroscopy revealed changes in functional groups including hydroxyl, carboxyl, and amide bands following mercury exposure, corroborating the surface binding mechanisms as presented in Figure 4. SEM micrographs showed distinct morphological differences between living and non-living biomass before and after mercury exposure, with living biomass maintaining its interconnected network structure as illustrated in Figure 1a & 1b while non-living biomass exhibited a more compact, aggregated structure with numerous micropores as shown in Figure 1c & 1d. This study demonstrates that living MIMA is particularly effective for rapid treatment of dilute mercury solutions, achieving high removal efficiencies within minutes without additional nutrients or CO₂ supplementation. Non-living biomass shows advantages in treating higher concentration solutions where toxicity would inhibit living cell performance. The substantial difference in kinetic behavior suggests that living MIMA employs both active biological processes and passive binding mechanisms, while non-living biomass relies primarily on surface adsorption and intraparticle diffusion. These findings contribute valuable insights to the development of sustainable mercury remediation strategies using indigenous microalgal resources. The complementary strengths of living and non-living MIMA suggest potential benefits in developing hybrid treatment approaches that capitalize on the advantages of both systems, offering versatile solutions for different application scenarios in mercury-contaminated water treatment.