2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(47c) Analysis of Carbon Intensities in Oil Refinery Distinguishing Fossil and Biomass Derived Feedstock

Authors

To achieve carbon neutrality in the chemical industry, it is essential to change raw materials from fossil resources into biomass and recycled-derived feedstock (Meng et al., 2023). In practice, used cooking oils, vegetable oils, and animal fats are being utilized. Also, pyrolysis oils from waste plastics are being employed. These materials are expected to be processed through pretreatment and then used alongside crude oil in the oil refining process, or directly fed into hydrodesulfurization units, fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) units, and petrochemical processes (Yáñez et al., 2020; ENEOS and Mitsubishi Chemical).

However, it has been demonstrated that the types and quantities of joint products differ between fossil, biomass and recycling ingredients (Pinho et al., 2022), as well as the environmental impacts of joint products (Kikuchi et al., 2022). Therefore, quantifying the amounts of joint products and the environmental impacts of these products by distinguishing raw materials, will contribute to achieve the carbon neutrality of chemical industry.

Previous studies have focused on the introduction of vegetable oils in FCC (Pinho et al., 2022) or their utilization as feedstocks in petrochemical processes (Kikuchi et al., 2022). There have yet to be any cases that distinguish between fossil and biomass derived feedstock in terms of flow and carbon intensities across the entire oil refinery (oil refining and petrochemical processes). In other words, strategies for refineries to achieve carbon neutrality in the chemical industry has not yet been identified.

Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the potential for reducing environmental impact of the entire oil refinery by distinguishing fossil and biomass feedstock by flow analysis and life cycle assessment (LCA). This study consists of setting system boundaries, selecting raw materials, developing the oil refinery model , conducting flow analysis, and LCA. This model enables us to conduct flow analysis, inventory analysis, and environmental impact assessment by distinguishing feedstocks. Cradle-to-gate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of joint products were calculated by multiplying the GHG emissions per throughput for each process by the throughput required to produce 1 kg of each joint products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System boundary

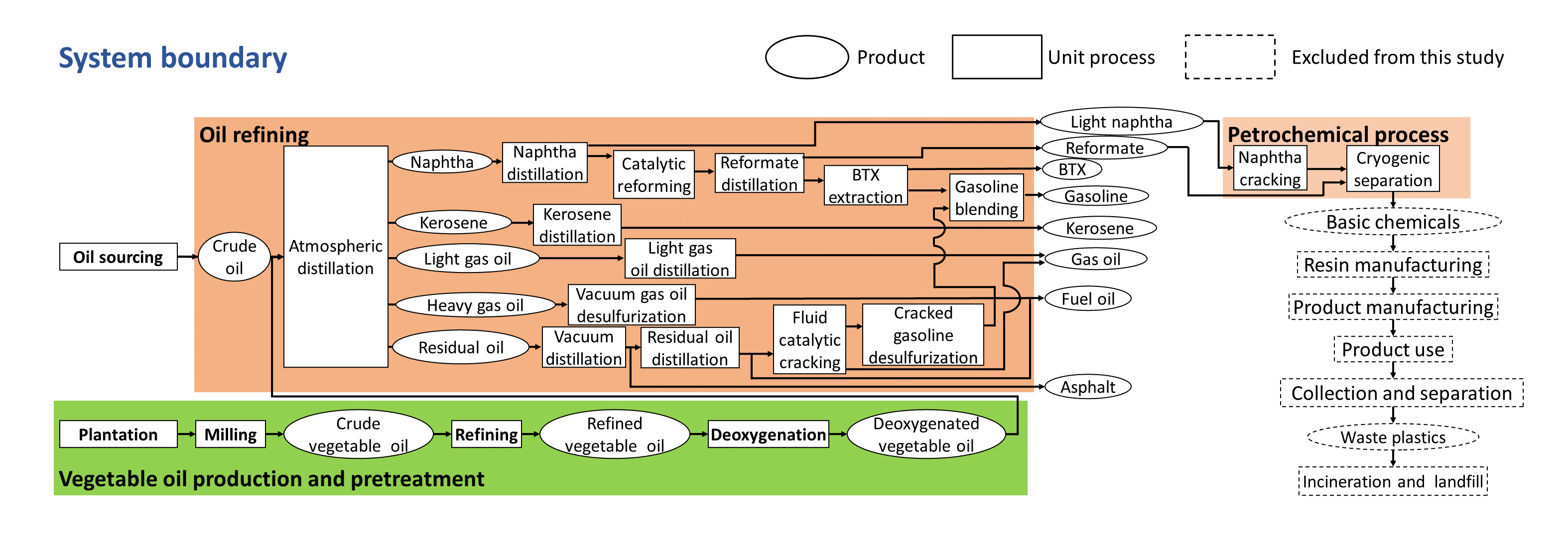

The system boundaries include raw material procurement, oil refining processes, petrochemical processes, and the pretreatment of vegetable oils. The target region is assumed to be Japan, and the model was developed based on the average oil refinery in Japan. The functional unit in the LCA was defined as the production of 1 kg of each joint product and basic chemical.

Since vegetable oils contain oxygen atoms in their ester bonds, it is necessary to break these ester bonds through deoxygenation or hydrogenation before being fed into the oil refinery. In this study, deoxygenation was selected, and the treated oil was fed into the atmospheric distillation in the oil refining process.

In Japan, the most distributed vegetable oils are rapeseed oil, palm oil, and soybean oil. Given that palm oil and soybean oil have similar fatty acid compositions, rapeseed oil and soybean oil was simulated.

2.2. Development of oil refinery model

A refinery model was developed that enables us to conduct flow analysis, inventory analysis, and environmental impact assessment by distinguishing between different ingredients. This model utilizes parameters such as the carbon number distribution of raw materials, capacities of unit operations, energy consumption per throughput of unit processes, and component yields. The oil refining process was modeled based on the average oil refining process in Japan as of 2020. For example, the capacity of the atmospheric distillation was set at 34,400 kL/day, and the CO2 emissions per throughput were set at 41.2 kg-CO2/kL. These capacities, component yields, and energy consumption per throughput of all unit in the oil refining processes were referenced from existing reports (JPEC, 2022), and an existing model for evaluating circular chemical recycling (Nakamura et al., 2024) was expanded to be applicable to vegetable oils by modifying oil refinery process and adding pretreatment of vegetable oils. The pretreatment of vegetable oils was modeled based on data from Neste's process (Nikander et al., 2008).

Vegetable oils consist of fatty acids and glycerin, with the carbon number of fatty acids varying depending on the type of vegetables. Therefore, in the refinery model, carbon numbers were simulated as follows: 1 to 4 for LPG fractions, 5 to 9 for naphtha fractions, 10 to 13 for kerosene fractions, 14 to 19 for light distillates fractions, 20 to 24 for medium distillates fractions, and 25 and above for heavy distillates. It was assumed that the fatty acids derived from vegetable oil fed into the atmospheric distillation were separated into various fractions, such as LPG fractions, according to their carbon numbers.

2.3. Flow analysis and LCA

The input quantities of raw materials were set as variables, and the objective function was defined to maximize the production of basic chemicals such as ethylene and BTX, while the processing capacities of each unit operation defined as constraints.

In the flow analysis, the production quantities of joint products and basic chemicals were calculated by tracking the component yields of each unit operation. The flow of fossil and vegetable oil derived materials were distinguished in the flow analysis.

For the environmental impact assessment, the production of 1 kg of joint products and basic chemicals was selected as the functional unit. Cradle-to-gate GHG emissions were calculated by multiplying the throughput required to produce 1 kg of joint products and basic chemicals by the GHG emissions associated with each unit operation.

3. Results and discussion

The results of the flow analysis quantitatively demonstrated that the type and quantity of joint products produced vary depending on the raw materials. For example, when using crude oil and rapeseed oil as feedstocks, the gas oil derived from crude oil was 5,574 tons/day, while the gas oil derived from rapeseed oil was 498 tons/day. Additionally, the basic chemicals derived from crude oil amounted to 1,739 tons/day, and those from rapeseed oil were 76 tons/day. In contrast, when using crude oil and soybean oil as feedstocks, the gas oil derived from crude oil was 5,535 tons/day, while the gas oil derived from soybean oil was 2,186 tons/day. The basic chemicals derived from crude oil were 1,727 tons/day, and those from soybean oil were 46 tons/day.

Rapeseed oil mainly contains of erucic acid (C22), which is equivalent to light distillates, and oleic acid (C18), which is equivalent to medium distillates, and they lead to a predominance of gas oil and heavy oil production. On the other hand, soybean oil primarily contains linoleic acid (C18), which is equivalent to light distillates, resulting in limited production of joint products other than gas oil. Thus, it was quantitatively shown that the carbon number distribution of the raw materials has a significant impact on the yield of products when fed into the atmospheric distillation unit.

In addition, the preliminary results of LCA are presented below. The cradle-to-gate GHG emissions of gas oil (including CO2 uptake) were 0.327, -1.05, 4.27 kg-CO2eq/kg-gas oil for crude oil, rapeseed oil, and soybean oil respectively. Also, these of olefins were 1.75, -0.132, and 5.91 kg-CO2eq/kg-olefins for crude oil, rapeseed oil, and soybean oil respectively. When considering CO2 uptake by biomass, products derived from rapeseed oil have lower GHG emissions compared to those derived from crude oil. However, products derived from soybean oil have higher GHG emissions than those derived from crude oil. This is because the significant environmental burden associated with the production of soybean. The results show that the selection of vegetable oil feedstock has a substantial impact on GHG emissions, which is crucial for achieving carbon neutrality in the chemical industry.

It has become possible to evaluate the decarbonization potential of oil refineries by combining the results of flow analysis and LCA. In addition, more realistic scenario analyses is possible by changing the input values, constraints, and objective functions.

4. Conclusion

In this study, an oil refinery model was developed to conduct flow analysis and environmental impact assessment. This model is characterized by its ability to distinguish between fossil and biomass derived materials. As a result, it has become possible to quantitatively demonstrate the yields and GHG emissions of joint products. It was shown that the yield of joint products is influenced by the carbon number of the raw materials. Additionally, it was revealed that, the cradle-to-gate GHG emissions can increase compared to those of crude oil-derived products depending on the choice of vegetable oils. This underscores the importance of selecting raw materials that can ensure sufficient yields to meet the demand for joint products while also enabling the reduction of cradle-to-gate GHG emissions in the pursuit of carbon neutrality in the chemical industry.

It is important to note that the evaluation results are highly dependent on the constraints and objective functions of the oil refinery model, making it crucial to consider plausible scenarios. Also, other environmental impacts besides GHG are also needed to analyzed. In the future, it will be necessary to conduct scenario analyses that consider the demand based on policies such as sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) and bio-based plastics, and explorer strategies for securing biomass.