2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(354i) What Drives the Breathing Transition in the MIL-53 Family of Metal-Organic Frameworks?

Authors

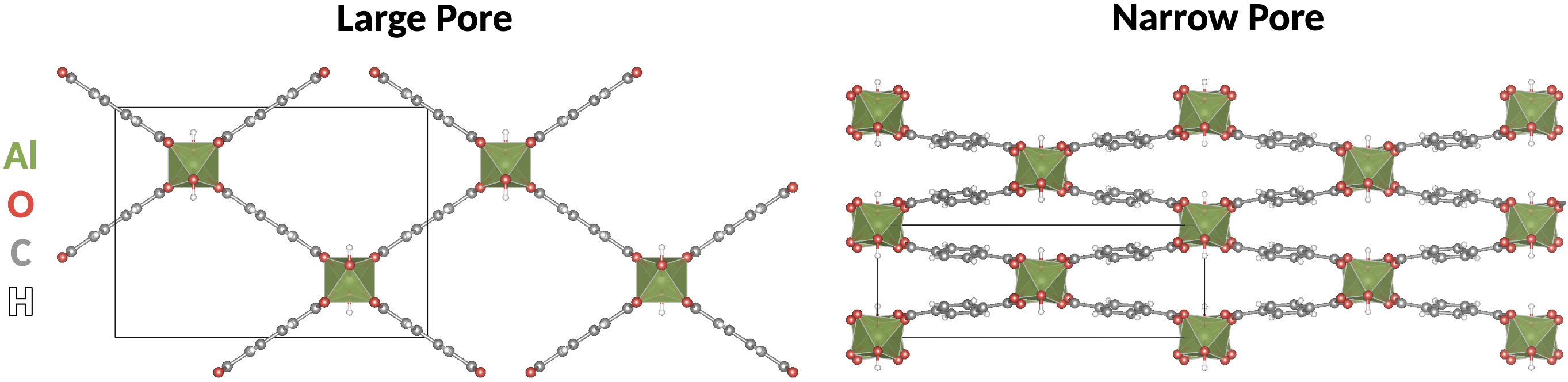

In this work, we use a combination of crystallographic symmetry principles, first-principles (DFT) calculations and phenomenological (Landau) theory to reveal the interplay between crystal structure and chemistry that permits the breathing transition in one MIL-53 family member but seemingly forbids it in another. This theoretical approach, not often employed in MOF studies, is commonly used in other fields, such as the complex oxides community. There it has delivered numerous insights into structure-property relationships that have helped advance both fundamental science and experimental work. We use it to show that the breathing transition is triggered by a vibrational mode of the large-pore phase, which breaks crystallographic symmetry and allows coupling to a shear strain that is otherwise symmetry-forbidden. This trigger mode is reminiscent of the soft modes that drive ferroelectric phase transitions in many perovskites. The increase in cell degrees of freedom is accompanied by a softening of the elastic constants, which is in turn associated with a significant decrease in the energetic barrier separating the large and narrow pore structures. Going further, we elucidate the role of the metal atom by examining a series of MIL-53 family members with metal nodes selected from group 13 elements Aluminum, Gallium, Indium, and Thallium. As metal ionic radius increases in the series we note a decreasing energetic resistance to cell compression, due to a weakening of repulsive local interactions associated with bond length and angle changes. This explains the experimentally observed trend of higher transition temperatures for larger metal ions. Finally, we show that whereas the inorganic backbones of the Aluminum, Gallium, Indium, and Thallium MIL-53 members display a flat energy surface with respect to displacements of the trigger mode, the linkers show significant energy reduction, suggesting that they provide the energetic driving force to trigger the breathing transition. MIL-53(Sc)’s inorganic backbone, however, energetically resists the trigger mode, clarifying its experimentally observed inflexibility. This detailed understanding of the mechanisms which control the breathing mode now opens the door for tailored structural engineering to manipulate MIL-53’s breathing behavior. Thus, this work lays the groundwork for tailoring stimuli-responsive elastic properties of MOFs via synthetic design according to intuitive chemical design principles.

[1] Y. Liu et. al. (2008). J. Am. Chem. Soc., 130, 11813.

[2] P.G. Yot et. al. (2014). Chem. Commun., 50, 9462.

[3] J. A. Mason et.al. (2015). Nature, 527, 357.

[4] C. Volkringer et. al. (2009). Dalton Trans., 12, 2241.

[5] A. Ghoufi et. al. (2012). J. Phys. Chem. C., 116, 13289.

[6] F. Millange et. al. (2008). Chem. Commun., 39, 4732.

[7] J. Mowat et. al. (2012). Dalton Trans., 41, 3979.

[8] K. Momma & F. Izumi (2011). J. Appl. Crystallogr., 44, 1272.