2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(39a) Tuning the Mechanical and Electrochemical Properties of Free-Standing Dry Electrode Films Via the Incorporation of Non-Fluorinated Binders to Dry Fibrillation Processing

Authors

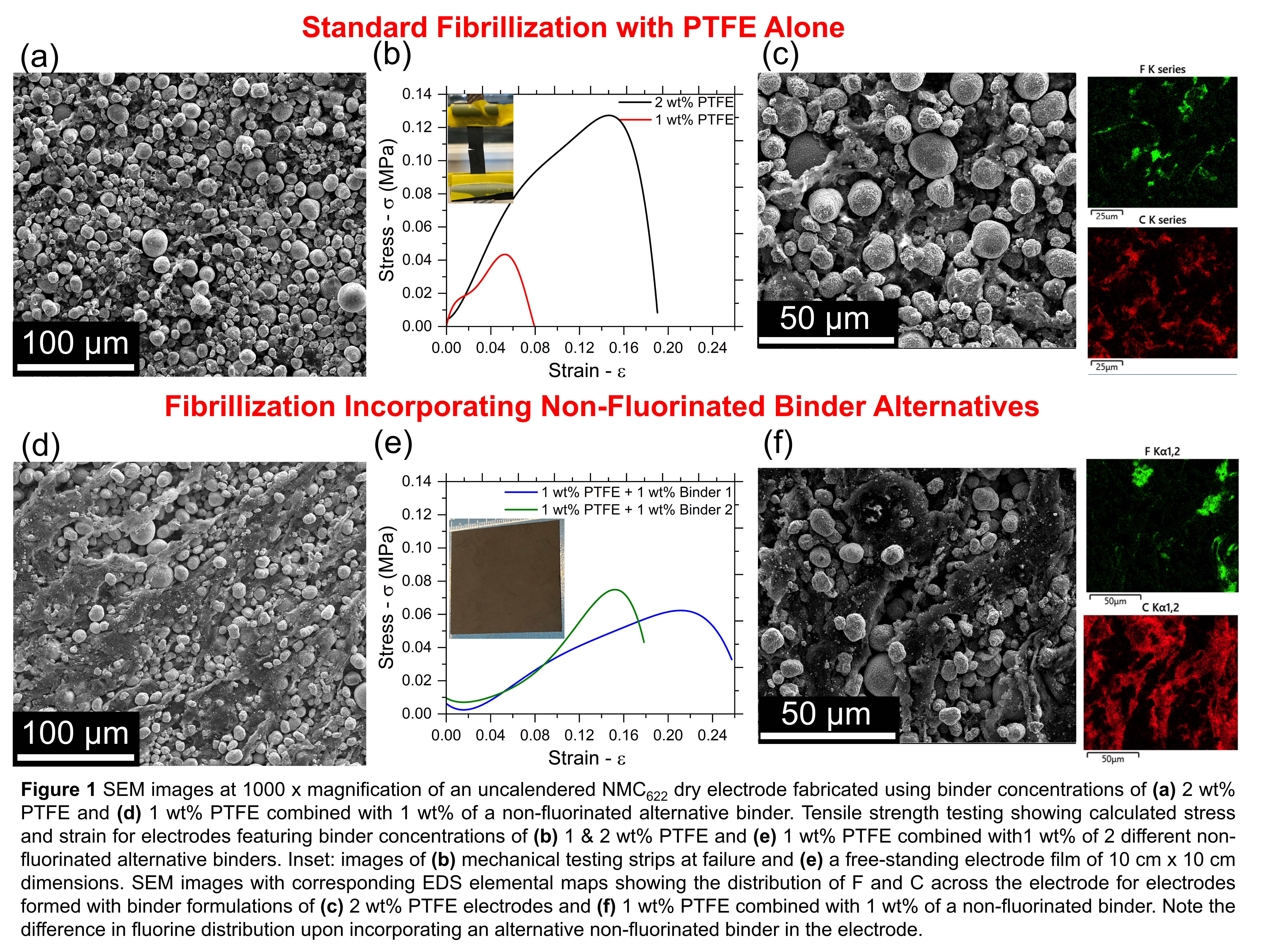

Perhaps the most well-documented dry electrode process, is the Maxwell-type polymer fibrillation technique through which a polymer is plastically deformed under applied heat and/or shear mixing to form thin, interconnecting fibrils which act as the binder material8. Critically, this technique shows industrial promise due to its compatibility with existing roll-to-roll manufacturing equipment used in electrode production1. At present, this technique is heavily reliant on PTFE as a binder due to its ability to fibrillate with very few true fibrillating alternatives present9. Although PTFE is the dominant fibrillation binder of choice for dry electrode manufacturing, it is not without issues for electrode manufacturing. For instance, poor adhesion between PTFE and the current collector necessitates the need for a primer coating on the current collector and the inherent hydrophobicity of PTFE can create issues with electrolyte wettability2 10. Additionally, fluoropolymers (such as PTFE and PVDF) are becoming increasing unpopular choices as binders due to environmental concerns of PFAS pollution and greenhouse gas emissions through their manufacture and application, with government regulations related to PFAS chemicals anticipated to scale back their use11. These manufacturing and environmental concerns highlight a need to propose alternative binders for this type of dry electrode manufacturing.

Here, we investigate alternative binders for use in Maxwell-type dry electrode manufacturing of NMC622 electrodes. The unique properties of PTFE fibrillisation have established it as a ubiquitous binder in this dry electrode manufacturing process. We explore the feasibility of lowering the overall PTFE content used as a binder for dry electrode processing through complexing it with several other promising non-fluorinated binder alternatives, assessing the electrochemical and mechanical properties of these composites. Additionally, we explore the beneficial role of plasticizer additives in these alternative binder formulations for selective tuning of the mechanical properties of the free-standing cathode sheets.

Tensile strength measurements evaluating ultimate stress and strain of free-standing electrode films fabricated from composite binder formulations demonstrate the potential benefits to the structural properties of the electrode film. Careful examination of SEM images and elemental mapping will explore the role and uptake of these non-fluorinated binder alternatives in the microstructure of the electrode sheets. Comparisons between the electrode sheet resistance and electrochemical cycling of the cathodes will explore the electrochemical performance of these dry electrode binder formulations. Current literature research commonly reports overall PTFE binder content utilised in quantities of 2 wt%12 13 14. We attempt to quantify the lower limit of PTFE necessary for constructing electrodes from composite binder mixtures while still maintaining structural integrity of the composite free-standing film and delivering high performance as an electrode. Importantly, the results presented here constitute major steps towards lowering the reliance of dry electrode fibrillization on PTFE, a significant advancement for optimising electrode performance and mitigating potential environmental impact of dry electrode manufacturing.

References

(1) Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Ma, T.; Chen, L.; Li, H.; Wu, F. Progress in solvent-free dry-film technology for batteries and supercapacitors. Materials Today 2022, 55, 92-109. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mattod.2022.04.008.

(2) Jin, W.; Song, G.; Yoo, J.-K.; Jung, S.-K.; Kim, T.-H.; Kim, J. Advancements in Dry Electrode Technologies: Towards Sustainable and Efficient Battery Manufacturing. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11 (17), e202400288. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/celc.202400288.

(3) Liu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Current and future lithium-ion battery manufacturing. iScience 2021, 24 (4), 102332. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102332.

(4) Liu, Y.; Shao, H.; Guo, J.; Yu, H.; Xu, H.; Xu, X.; Deng, Y.; Wang, J.; Yan, H. Toward scale-up of solid-state battery via dry electrode technology. Next Energy 2025, 7, 100221. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nxener.2024.100221.

(5) Westphal, B. G.; Kwade, A. Critical electrode properties and drying conditions causing component segregation in graphitic anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Journal of Energy Storage 2018, 18, 509-517. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2018.06.009.

(6) Font, F.; Protas, B.; Richardson, G.; Foster, J. M. Binder migration during drying of lithium-ion battery electrodes: Modelling and comparison to experiment. Journal of Power Sources 2018, 393, 177-185. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2018.04.097.

(7) Oh, H.; Kim, G.-S.; Bang, J.; Kim, S.; Jeong, K.-M. Dry-processed thick electrode design with a porous conductive agent enabling 20 mA h cm−2 for high-energy-density lithium-ion batteries. Energy & Environmental Science 2025, 18 (2), 645-658, 10.1039/D4EE04106B. DOI: 10.1039/D4EE04106B.

(8) Lu, Y.; Zhao, C.-Z.; Yuan, H.; Hu, J.-K.; Huang, J.-Q.; Zhang, Q. Dry electrode technology, the rising star in solid-state battery industrialization. Matter 2022, 5 (3), 876-898. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matt.2022.01.011.

(9) Schmidt, F.; Kirchhoff, S.; Jägle, K.; De, A.; Ehrling, S.; Härtel, P.; Dörfler, S.; Abendroth, T.; Schumm, B.; Althues, H.; et al. Sustainable Protein-Based Binder for Lithium-Sulfur Cathodes Processed by a Solvent-Free Dry-Coating Method. ChemSusChem 2022, 15 (22), e202201320. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.202201320.

(10) Zhang, K.; Li, D.; Wang, X.; Gao, J.; Shen, H.; Zhang, H.; Rong, C.; Chen, Z. Dry Electrode Processing Technology and Binders. Materials 2024, 17 (10), 2349.

(11) Wahlström, M. e. a. 2021. https://www.eionet.europa.eu/etcs/etc-wmge/products/etc-wmge-reports/fluorinated-polymers-in-a-low-carbon-circular-and-toxic-free-economy (accessed 2025 14/01).

(12) Suh, Y.; Koo, J. K.; Im, H.-j.; Kim, Y.-J. Astonishing performance improvements of dry-film graphite anode for reliable lithium-ion batteries. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 476, 146299. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.146299.

(13) Lee, T.; An, J.; Chung, W. J.; Kim, H.; Cho, Y.; Song, H.; Lee, H.; Kang, J. H.; Choi, J. W. Non-Electroconductive Polymer Coating on Graphite Mitigating Electrochemical Degradation of PTFE for a Dry-Processed Lithium-Ion Battery Anode. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2024, 16 (7), 8930-8938. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.3c18862.

(14) Wei, Z.; Kong, D.; Quan, L.; He, J.; Liu, J.; Tang, Z.; Chen, S.; Cai, Q.; Zhang, R.; Liu, H.; et al. Removing electrochemical constraints on polytetrafluoroethylene as dry-process binder for high-loading graphite anodes. Joule 2024, 8 (5), 1350-1363. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2024.01.028.