2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(445b) Towards Greater Understanding of Lysozyme Crystallization: Investigations into Impurities and Rate Expressions for a Batch Seeded Process

Authors

During the design and operation of the protein crystallization process, it is crucial to ensure critical quality attributes (CQAs) meet desired specifications. A key challenge encountered during the design process is the stochastic (random) nature of nucleation which could vary greatly depending on supersaturation and solution volume, complicating the control of crystal product properties. To circumvent this problem, the addition of seeds enhances nucleation and shifts the system to be more growth-focussed, as seeds provide pre-existing sites for solute molecules to attach to, reducing the randomness of the process. This allows for better control of size and polymorphism. Seeds do not have to be of the same material as the crystallized species, but some foreign substances provide an inhibiting effect rather than enhancing the crystallization process. Another challenge specific to protein crystallization is the lack of knowledge regarding rate expressions, impeding process understanding which would facilitate further activities such as optimisation.

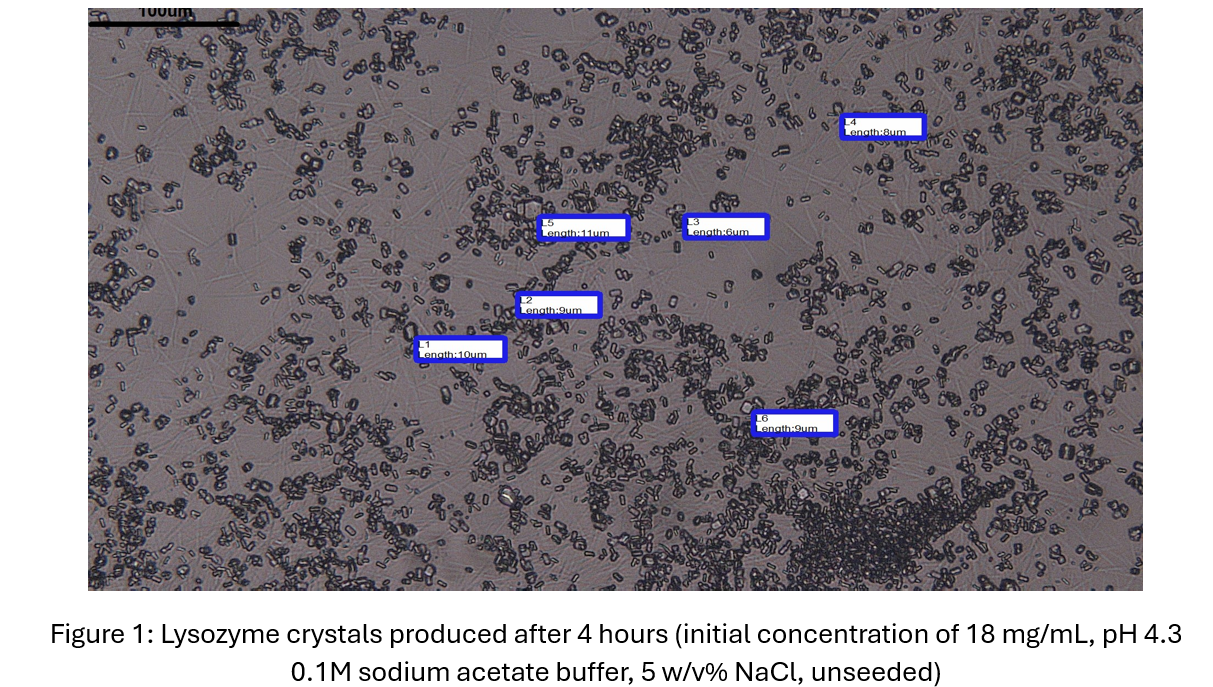

In this work, we present the development and further study of a batch seeded precipitant-induced lysozyme crystallization process in three parts: 1) Initially obtaining system understanding from unseeded experiments (NaCl as precipitant), leading to an appropriate experimental protocol being obtained by varying seed addition; 2) Brief investigations into the effect of additional impurities present in the system; and 3) From experimental data, begin an exploration into potential rate expressions for lysozyme crystallization, potentially extending to the inhibitory effect of impurities.

Initially, 50 mL unseeded lysozyme crystallization experiments at room temperature were first conducted at varying supersaturations. These were guided by existing solubility data from literature, with the objective of obtaining an unseeded induction time of around 100-200 minutes to ensure seed-enhanced nucleation reduces induction time to a point where the process can still be adequately controlled. To monitor lysozyme concentration in the solution, UV-Vis spectrophotometry measurements (Thermo Scientific NanoDrop One) were taken at regular intervals. After an appropriate experimental protocol was obtained (initial lysozyme concentrations of around 18-19 mg/mL), silica seeds of varying porosity (nonporous and mesoporous), pore sizes (~4nm) and particle sizes (<150 μm) were added, with the effect on PSD (measured via laser diffraction using an Anton Paar particle size analyser) and induction time investigated. It was found that silica was able to reduce induction time by up to 50%.

As silica markedly enhanced nucleation by reducing induction time, the effect of crystallization inhibiting impurities was also investigated, with thaumatin and albumin being known examples for lysozyme. To do this, varying amounts of impurities were added to both unseeded and seeded lysozyme crystallization experiments. It was found that in some cases, seeding proved effective in separating lysozyme from an impurity-containing solution.

To assist with finding appropriate expressions for nucleation and growth rates, gPROMS’ Mixed Suspension Mixed Product Removal (MSMPR) Crystallizer model library was used. This approach was selected as the MSMPR model is a first-principles process model which already contains all the necessary equations (mass, energy and population balances), with the flexibility of customisable nucleation and growth rate equations. As gPROMS’ in-built parameter estimation capabilities allows for quick statistical analysis of whether a selected expression fits experimental data well, this allowed for quick exploration of potential rate equations without having to build a process model from scratch.

It was found that empirical adjustments to conventional nucleation and growth models normally used for small molecules were required, which was expected as protein crystallization is a complex process (for example, classical nucleation theory is unable to predict protein nucleation rates). Furthermore, terms for inhibitory effect of impurities such as thaumatin and albumin were considered. A quantitative assessment of the adjustments was provided by gPROMS’ goodness of fit, bias, and lack of fit tests, along with further analysis (variance – covariance, and correlation matrices).

In summary, this work aims to provide not only a case study demonstrating the successful design of a batch seeded protein crystallization process, but also an initial foray into impurities and rate expressions for protein crystallization.

The implication of this work is that if successful, it could enable the eventual proposal of a workflow that could be transferred to other peptide/proteins and accelerate the adoption of protein crystallisation as a go to purification method in industry.