2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(263e) Thermal Imaging for Chemical Engineering Education

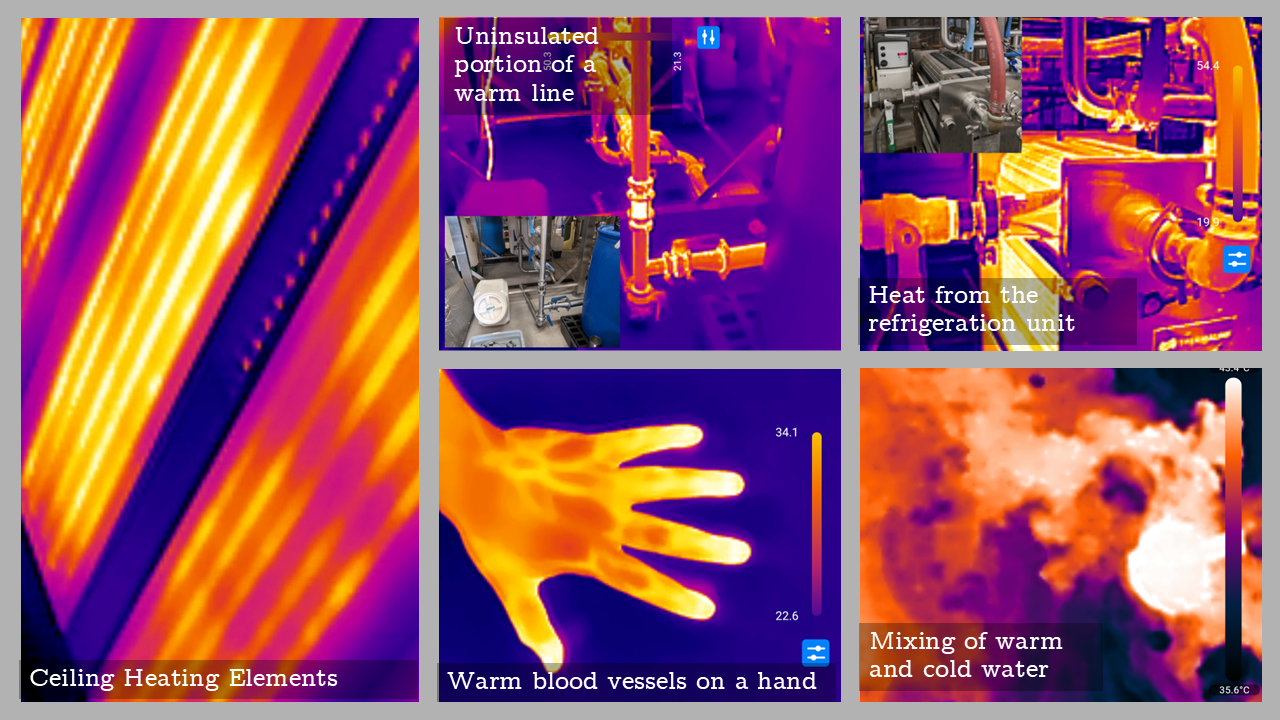

Several chemical engineering phenomena involve temperature variations that could benefit from visualization. In our study we found these cameras to be particularly useful in the heat transfer module of the transport sequence. We can visualize not only invisible sources of heat generation such as radiators and electric heating elements but also any flames due to contrasting temperature differences. Heat pumped by a refrigeration cycle becomes evident along the piping as the refrigerant absorbs and releases heat. We also observe the formation of Benard-Rayleigh convection cells in warm water that appears still to the naked eye. Other heat transfer phenomena we can directly observe include hand warmers, evaporative cooling, frictional heating, biological heating and cooling, and infrared reflective glasses. We include several of these thermal photographs in the accompanying image (the temperature scales are in Celsius).

The benefits also extend to other chemical engineering courses. Chemical reactions (exothermic or endothermic) also become visually discernible, as do any warm sublimates exiting a chemical reaction. Flow and mixing of fluids of dissimilar temperatures and viscous heating can also be observed with greater clarity. Finally, any equipment may be vetted for any insulation or material leaks, as we are effectively placing a thermocouple at every pixel in the field of view of the camera. This capability can further be exploited to design safety devices that constantly monitor temperatures in the field of view.

We propose the inclusion of such portable thermal imagers both within and outside the chemical engineering classroom. Within the classroom, these cameras augment in-class demonstrations where temperature variation may be present. With a handful of such camera modules, this idea can be further molded into an open-ended activity where students take cameras outside of the classroom to observe everyday phenomena. There is an abundance of unusual thermal phenomena in this context, which prompts individual scientific exploration for the students. This way, the students will be able to connect in-class theory of conduction, convection, and radiation with the real-world context. To this end, we provide sample activities that are readily integrated into the standard chemical engineering curriculum. Finally, we talk about the limitations and sharp bits of using such cameras, along with the possibilities of future implementations and further study of their pedagogical effectiveness.

In summary, we find that the use of thermal cameras can reveal the ubiquity of heat transfer phenomena in chemical engineering and in our everyday life. We hope that these learning modules will allow future chemical engineers to develop a better relationship with temperature, which is often an invisible (yet crucial) presence.