2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(669f) Separation of Volatile Fatty Acids By Simulated Moving Bed

Authors

Several methods have already been researched for this end, such as precipitation, liquid-liquid extraction, distillation, gas stripping, adsorption and membrane-based processes (e.g., pervaporation, membrane contactor, nanofiltration, reverse osmosis). Adsorption is a highly studied separation method, since it is relatively easy to operate, has high selectivity, and a variety of materials [1, 3]. Volatile fatty acids adsorption has been explored using different materials, mainly polymeric adsorbents nonfunctionalized and functionalized with primary, secondary, tertiary amines and quaternary ammonium. The adsorbents with tertiary amine functional group showed higher adsorption capacity of the VFA, and nonfunctionalized materials presented different affinities to each acid. These materials were used successfully in multiple studies to remove and/or recover volatile fatty acids from synthetic or real fermented solutions. However, the investigation of VFA fractionation remains largely unexplored [4-10].

Methodology. This work intends to report a complete analysis of adsorption/desorption of volatile fatty acids, as well as a selective separation of acetic and propanoic acids (produced in higher amounts during acidogenic fermentation). Therefore, adsorption equilibrium was assessed by performing batch experiments in different polymeric adsorbents (one non-functionalized, two functionalized with tertiary amine, and one functionalized with quaternary ammonium), with single-component aqueous solutions of the following VFA: acetic, propanoic, butyric, isobutyric, valeric, isovaleric and hexanoic acids. The experimental data was fitted with the appropriate model. Adsorption-desorption cycles were also analysed in a lab-scale fixed-bed set-up, packed with the adsorbent that showed different affinities to each volatile fatty acid in the batch experiments. Single and multicomponent breakthrough curves were obtained during these essays, which allowed the validation of the mathematical model applied, as well as the equilibrium and kinetic parameters. Furthermore, the Simulated Moving Bed (SMB) unit available in the LSRE-LCM group (FlexSMB) was operated for VFA fractionation, specifically of acetic and propanoic acids in a binary solution. The SMB experimental results were used to model a SMB in cascade to separate acetic and propanoic acids from a VFA mixture produced through acidogenic fermentation of wastewater.

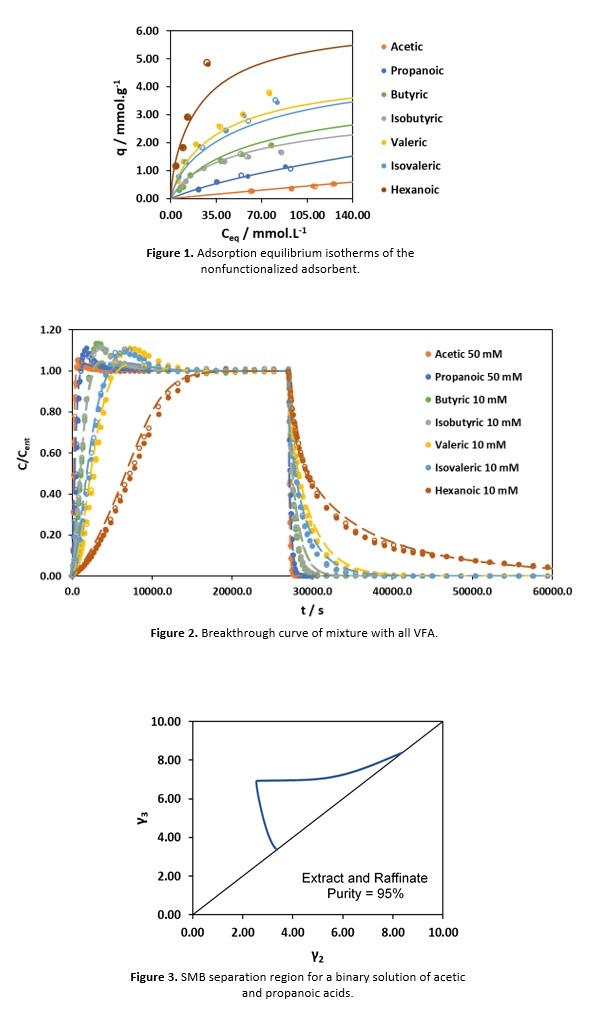

Results and discussion. The adsorption equilibrium isotherms obtained, at 25 °C and pH 3, showed similar adsorption capacity for every acid, in the adsorbents functionalized with a tertiary amine, and different affinities to each acid when using the adsorbents nonfunctionalized and functionalized with a quaternary ammonium. The nonfunctionalized adsorbent was selected to perform VFA fractionation since it displayed higher and different affinities to each acid. In Figure 1 (presented below), the adsorption equilibrium data for the nonfunctionalized adsorbent, as well as the dual-site Langmuir model adjustment, can be conferred.

Breakthrough curves were acquired for single-component solutions of every acid in study, for binary solutions of acetic acid with every other acid, propanoic acid with every other acid and for a multicomponent solution with all VFA, at pH 3 and room temperature (22-25 °C). In the desorption step, water was used as desorbent, that way the adsorption equilibrium isotherms could be used in the mathematical model simulations for both breakthrough steps. The breakthrough curve of the mixture with all the acids is shown in Figure 2 (presented below), as well as the mathematical model predictions (in dashed lines). The mathematical model applied (dual-site Langmuir model for equilibrium, and Linear driving force model for mass transfer inside the adsorbent) was able to give good predictions of the experimental results.

Modelling of the FlexSMB unit was conducted to determine the separation region for a binary solution of acetic and propanoic acids and the most appropriate operating conditions (switching time and flow rates) to perform the experimental essay. In Figure 3 (presented below), the separation region obtained at a 95% purity of raffinate and extract streams is represented. The mathematical model validation was completed by comparing experimental results with the simulations of the SMB. Then, the SMB in cascade was designed.

References

- Atasoy, M., et al. Bioresource Technology, 2018. 268: p. 773-786.

- Aghapour Aktij, S., et al. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 2020. 81: p. 24-40.

- Pervez, M.N., et al. Science of The Total Environment, 2022. 817: p. 152993.

- Silva, A. and E. Miranda. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data, 2013. 58: p. 1454–1463.

- Yousuf, A., et al. Bioresource Technology, 2016. 217: p. 137-140.

- Rebecchi, S., et al. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2016. 306: p. 629-639.

- Fargues, C., et al. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 2010. 49(19): p. 9248-9257.

- Wu, H., et al. Separation and Purification Technology, 2021. 265: p. 118108.

- Reyhanitash, E., et al. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 2017. 5(10): p. 9176-9184.

- Eregowda, T., et al. Separation Science and Technology, 2019: p. 1-13.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by national funds through FCT/MCTES (PIDDAC): LSRE-LCM, UIDB/50020/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/UIDB/50020/2020) and UIDP/50020/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/UIDP/50020/2020); and ALiCE, LA/P/0045/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/LA/P/0045/2020). Cristiana Gomes acknowledges her PhD scholarship 2021.05666.BD funded by FEDER funds through NORTE 2020 and by national funds through FCT/MCTES.