2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(246b) Recycling Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Dielectrophoretic Filtration

EV battery waste is expected to amount to 20.5 million tonnes in 2040 [2]. However, current global LIB recycling capacity is 1.6 million tonnes/year [3], highlighting the need to significantly boost our recycling capabilities. Current recycling technologies include hydrometallurgy and pyrometallurgy which are chemically and energy intense and cannot recover all materials. Graphite – listed as a critical raw material by the EU – is not recovered in current recycling processes [4]. Therefore, we must develop more energy-efficient and cost-effective battery recycling techniques to avoid an accumulation of LIBs in landfills, secure LIB raw material supply and reach EU recycling targets.

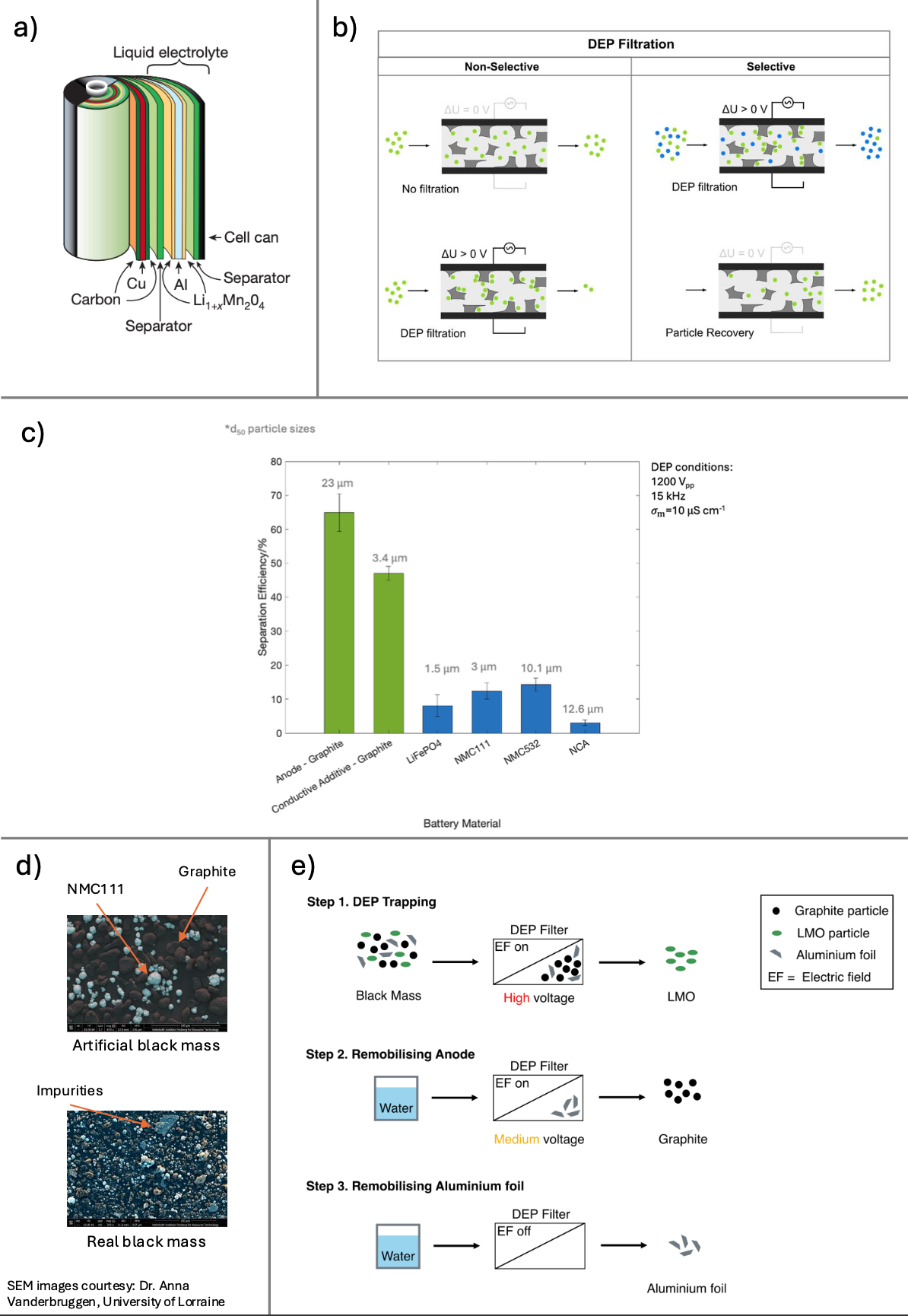

We propose to use dielectrophoretic (DEP) filtration as a direct LIB recycling process without chemical alteration steps. LIBs consist of an anode, cathode, aluminium and copper foil, plastic housing, a separator, electrolyte and polymeric binder (Fig. a) [5]. The two major components of LIBs include graphite as the anode and lithium metal oxide (LMO) as the cathode, potentially containing Co, Mn, Ni and Al. Black mass (BM) is a shredded intermediate product of waste LIBs. It is a fine-powdered mixture of graphite, LMO and aluminium foil. Dielectrophoresis (DEP) is an electrokinetic microparticle separation technique offering an environmentally-friendly method to separate BM particles based on their differences in composition, size, shape and polarisability [6]. DEP describes the movement of polarisable particles in non-uniform electric fields. The magnitude and direction of DEP movement depends on particle size, shape and polarisability. Depending on their polarisability relative to the medium (water), particles move either towards or away from local electric field maxima. If a particle is more polarisable than the medium, it experiences positive DEP and moves toward field maxima. Whereas, if a particle is less polarisable than the medium, it exhibits negative DEP by moving away from field maxima.

DEP filtration – a high throughput DEP method – involves passing an aqueous particle suspension through a dielectric filtration matrix positioned in an applied AC electric field. The filtration matrix disrupts the electric field, causing local electric field inhomogeneities in the filter pores, resulting in local field maxima near pore edges. This allows a selective and switchable separation of particles that experience positive DEP from a particle mixture (Fig. b).

For example, graphite and aluminium are conductive particles and will move towards field maxima and become immobilised in those regions. On the other hand, cathode particles (LMO) generally possess low conductivity and will move away from field maxima. As a result, LMOs flow straight through a DEP filter. Differences in polarisability, shape and size of each BM component (anode, cathode, aluminium) provide a strong basis for successful particle separation of BM using DEP filtration. Separation of BM particles using DEP filtration was first demonstrated by Kepper and co-workers in 2024, in which graphite and LiFePO4 (a common LMO) were separated based on their differences in polarisability [7].

In this project, the selective separation of BM components using DEP filtration and its scalability will be examined. Firstly, particle behaviour of BM materials at varying DEP conditions are analysed under a microscope. Materials investigated are anodic graphite, a conductive additive material and common LMOs including LiFePO4, LiNi0.33Mn0.33C0.33O2 (NMC111), LiNi0.5Mn0.3C0.2O2 (NMC532) and LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2 (NCA). Non-selective DEP filtration was performed on each BM material to understand the effect of various DEP parameters (voltage, frequency, medium conductivity).

Initial results indicate that the separation efficiency of anode (graphite) and cathode (LMO) materials vary significantly (Fig. c). Conductive anode particles exhibit higher trapping rates inside the filter compared to semi-conductive cathode materials regardless of particle size. Results suggest that DEP filtration can be used to separate a anode/cathode mixture based on their conductivity differences rather than size-based separation. This reduces our reliance on uniform particle sizes when separating real BM samples in the future.

Next, artificial BM mixtures of graphite and LMOs (Fig. d, top) will be separated based on their distinct conductivities using DEP filtration. Graphite is expected to become trapped (positive DEP) whilst most LMO particles flow through (negative DEP). The effect of voltage, frequency, medium conductivity and flow rate on separation efficiency and selectivity will be determined. Following this, a ternary BM mixture of graphite, LMO and aluminium foil will be separated using a multistep DEP filtration process (Fig. e). Conductivity and particle shape of aluminium foil differs from that of graphite resulting in varied DEP behaviour. Aluminium foil is expected to remain inside the DEP filter even at low voltages whilst, graphite experiences a weakened DEP force and remobilises. This results in the separation of BM into three particle streams. Finally, real BM (Fig d, bottom) from battery recycling plants will be separated using DEP filtration and the effect of contaminants on separation efficiency and purity will be investigated.

As our dependence on LIBs continues to grow, it is vital that we develop sustainable and robust LIB recycling methods capable of achieving industrial scale to improve current recycling rates. Therefore, investigating the scalability LIB recycling using DEP filtration (e.g. increasing flow rate and filter cross-sectional area) is considered a crucial element of this research. In addition, the findings of this project will build foundations of using DEP filtration to solve other intricate particle separation problems such as mineral ore refining and WEEE recycling.

References

[1] Power Technology, https://www.power-technology.com/news/globaldata-global-ev-growth-forec…, accessed Jan 2025

[2] McKinsey & Company, 2023

[3] Lithium-ion Battery Recycling Market and Innovation Trends for A Green Future, Deloitte, 2025

[4] A. Hogan, ME Thesis, University College Dublin, 2023

[5] J. M. Tarascon, M. Armand, Nature, 2001, 414, 359–367

[6] G. Pesch, F. Du, 2021, Electrophoresis, 42, 134–152

[7] M. Kepper et. al, 2024, Results in Engineering 21, 101854