2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(402a) Recovery of Metallic Iron from the Loaded Organic Phase After Solvent Extraction by Precipitation-Stripping with Hydrogen Gas

We studied the experimental conditions for the precipitation of metallic iron. The solids formed in the organic phase were characterized to determine their chemical composition, purity, morphology, and particle size distribution. The objective was to find the mildest-possible experimental conditions to obtain a well-filterable metallic phase. Two different bases were tested: NH3(g) and Mg(OH)2. Mg(OH)2 is readily soluble in Versatic Acid 10 via an acid-base reaction, even at temperatures below 100 °C. Such base addition helped to shift the reaction equilibrium to the right for this kinetically very slow reaction in the case of iron [5]. The relevant reactions are: and , where V is the organic acidic extractant Versatic.

The experiments were carried out in 80 mL Hastelloy reactors in a multiple reactor system (Parr industry) with p(H2) ≤ 10 bar. The organic solutions (Fe, 3–5g/L; 10-30 vol.% in the diluent Shell GTL Fluid G80) loaded into the reactor were previously obtained by the loading of Fe from an aqueous Fe2(SO4)3 solutions of Fe(III) [8]. Seeding particles were added to aid the precipitation, with Ni or Fe seeds (<5 µm). The reactors were loaded with 15 to 30 mL of organic solution and with solid Mg(OH)2 or of NH3 gas. The stoichiometric excess of H2 over Fe could reach 15. After 2 hours at 200 °C, the reactor was cooled and the solid formed was then filtered through a 1.6 µm filter, rinsed with ethanol, dried under vacuum at 50 °C and then stored under N2 atmosphere, until its characterization by XRD and SEM-EDX. The residual organic solution was analyzed by ICP-OES in a pure organic 1-butanol matrix, to measure the Fe, Mg and Ni concentrations. In all experiments where Mg(OH)2 was added, the Mg concentrations showed the total dissolution of the pre-loaded Mg(OH)2 solid. No Ni of the Ni seeds went into solution.

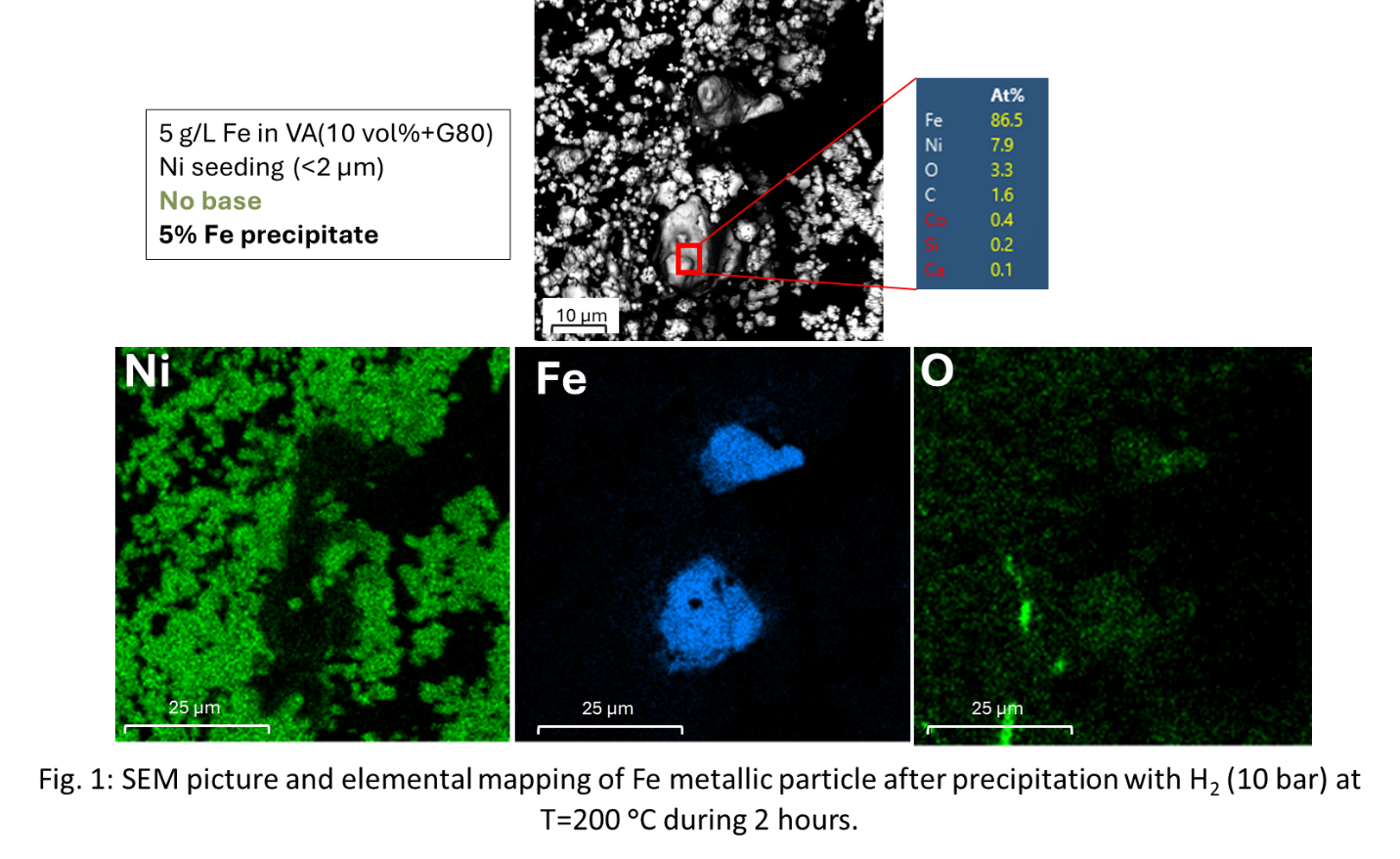

The Fe precipitation yields gave higher dissolution in the presence of a base, e.g. 5% Fe precipitate without base vs 13% with Mg(OH)2. With the use of Fe seeds with Mg(OH)2, the precipitation yields were higher for Fe (40%) rather than with Ni seeds (13%). These observations can be explained by SEM-EDX results in the presence of Ni seeds, which show pure Fe precipitation (Fig. 1). For the first time, metallic iron particles obtained directly from a loaded organic phase have been characterized by SEM-EDX analysis, and they typically have a size between 10 and 20 µm (Fig. 1). The XRD diffractograms do not give direct indication for formation of metallic particles because the peaks of Ni metal are overlapping with those of Fe metal. However, no iron oxide peaks were observed. Upon using NH3 as a base, a metal-rich third phase was formed, demonstrating the need for a phase modifier such as 1-decanol.

This work illustrates the differences in metal precipitation mechanisms in Versatic Acid 10 and the ability to replace NH3 by the solid base Mg(OH)2 to aid in the reduction of Fe in metallic form from organic SX solution. The Mg(II) in the organic phases can be replaced by another metal ion such as Fe(III) by exchange extraction upon contacting it with an iron-rich aqueous solution. MgSO4 can be recovered from the Mg-rich aqueous solution by evaporation of water, giving a certain circularity to the process by the reuse of the organic solution.

References

[1] W. J. S. Craigen, G. M. Ritcey, et B. H. Lucas, Byproduct Fe–discard or recover, Can Min Met. Bull, vol. 68, no 756, p. 70‑83, 1975.

[2] A. J. Monhemius, The iron elephant: A brief history of hydrometallurgists’ struggles with element no. 26, CIM J, vol. 8, no 10.15834, 2017.

[3] J. Lee, K. Kurniawan, Y. J. Suh, et B. D. Pandey, Uses of H2 and CO2 gases in hydrometallurgical processes: Potential towards sustainable pretreatment, metal production and carbon neutrality, Hydrometallurgy, vol. 234, p. 106468, 2025.

[4] K. Binnemans et P. T. Jones, The twelve principles of circular hydrometallurgy, J. Sustain. Metall., vol. 9, no 1, p. 1‑25, 2023.

[5] G. P. Demopoulos et P. A. Distin, Pressure hydrogen stripping in solvent extraction, JOM, vol. 37, no 7, p. 46‑52, 1985.

[6] G. P. Demopoulos et D. L. Gefvert, Iron(III) removal from base-metal electrolyte solutions by solvent extraction, Hydrometallurgy, vol. 12, no 3, p. 299‑315, 1984.

[7] A. R. Burkin, Production of some metal powders by hydrometallurgical processes, Powder Metall., vol. 12, no 23, p. 243‑250, 1969, doi: 10.1179/pom.1969.12.23.012.

[8] J. S. Preston, Solvent extraction of metals by carboxylic acids, Hydrometallurgy, vol. 14, no 2, p. 171‑188, 1985.