2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(291a) Real-Time Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Numerical Modelling of Hydrodynamics in Vibrated Bubbling Fluidized Beds

Authors

Fluidized beds are widely used in various processes due to the increased solid-fluid contact. Additionally, it is possible to further enhance the fluidization behavior of a system through mechanical vibration. Previous studies have shown that vibration induces a reduction in the minimum fluidization velocity and minimizes gas channeling and particle agglomeration [1,2]. This makes vibrated fluidized beds a preferred choice in many processes. Despite their widespread use, our fundamental physical understanding of the hydrodynamics occurring within vibrated fluidized beds is still limited. The main reason for this shortcoming is the fact that the spatial distribution of the phases is challenging to investigate experimentally because the systems are optically opaque. Additionally, conventional measurement techniques, such as intrusive probes, only yield solid concentration, particle velocity and bubble characteristics from one specific location of the bed and alter the flow. Therefore, non-intrusive tomographic techniques are increasingly being used to study them. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a technique that has been mainly applied in the medical field, is particularly suited for obtaining spatially and temporally resolved dynamic information from the interior of vibrated fluidized beds [3]. In addition to experimental studies, numerical simulations can be used to gain an insight into the hydrodynamics during fluidization. A promising approach for simulating fluidized beds is the method known as CFD-DEM, which combines computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and the discrete element method (DEM).

Numerical and Experimental Methods

The MRI measurements were conducted using a unique large-bore vertical magnet (3 T) located at the Institute of Process Imaging at TUHH. A three-dimensional fluidized bed with an outer diameter of 300 mm and a height of 1500 mm, as well as a fluidized bed with an outer diameter of 100 mm and a height of 1000 mm were investigated. The fluidized beds are made of PMMA, and sintered polyethylene porous plates were used as distributor plates. An electrodynamic shaker was used as the vibration source, with vertical vibrations transmitted from the electrodynamic shaker to the fluidized bed via a glass fiber tube. Due to the limited field of view (300 mm) in the scanner, the sample position inside the magnet bore was adjusted to investigate different sections of the fluidized bed. The impact of vibration on bubble characteristics was investigated with peak-to-peak amplitudes of up to 3 mm and frequencies of up to 150 Hz using MRI-visible Geldart group B and D particles. Time-efficient MRI pulse sequences were combined with image reconstruction and post-processing algorithms to track gas bubbles, detect bubble coalescence and splitting, and identify common bubble shapes in consecutive frames of an image time series.

Additionally, digital image analysis was used to investigate bubble properties in a vibrated pseudo-2D fluidized bed. The fluidized bed is made of PMMA, with a bed thickness of 1 cm and a bed width of 20 cm. Glass beads with diameters of 0.3, 0.5 and 0.9 mm were used for the pseudo-2D experiments.

The CFD-DEM simulations were carried out in open-source simulation tools, specifically utilizing OpenFOAM [4] for the CFD calculations coupled with LIGGGHTS [5] to account for the DEM simulation of particle contacts. CFDEMcoupling [6] was used as the coupling module. To achieve comparability between the simulations and experiments three different geometries, namely a rectangular bed with the same dimensions as the one used for the pseudo-2D measurements and two cylindrical beds with dimensions equal to those of the three-dimensional beds for the MRI measurements, were used. For the modelling of the glass particles, that were used in the pseudo-2D bed, standard values for restitution and friction coefficients were used, while the particle properties for the MRI-visible particles were calibrated by performing restitution coefficient, angle of repose and shear cell experiments. To model the vibration in the simulations the gravity was oscillated following , where is the time and and are vibration frequency and amplitude, respectively. In addition to the mechanical vibration of the apparatus an oscillating gas inlet flow is also investigated in the simulations. From the simulation data bubble positions, sizes and rising velocities were calculated.

Results and Discussion

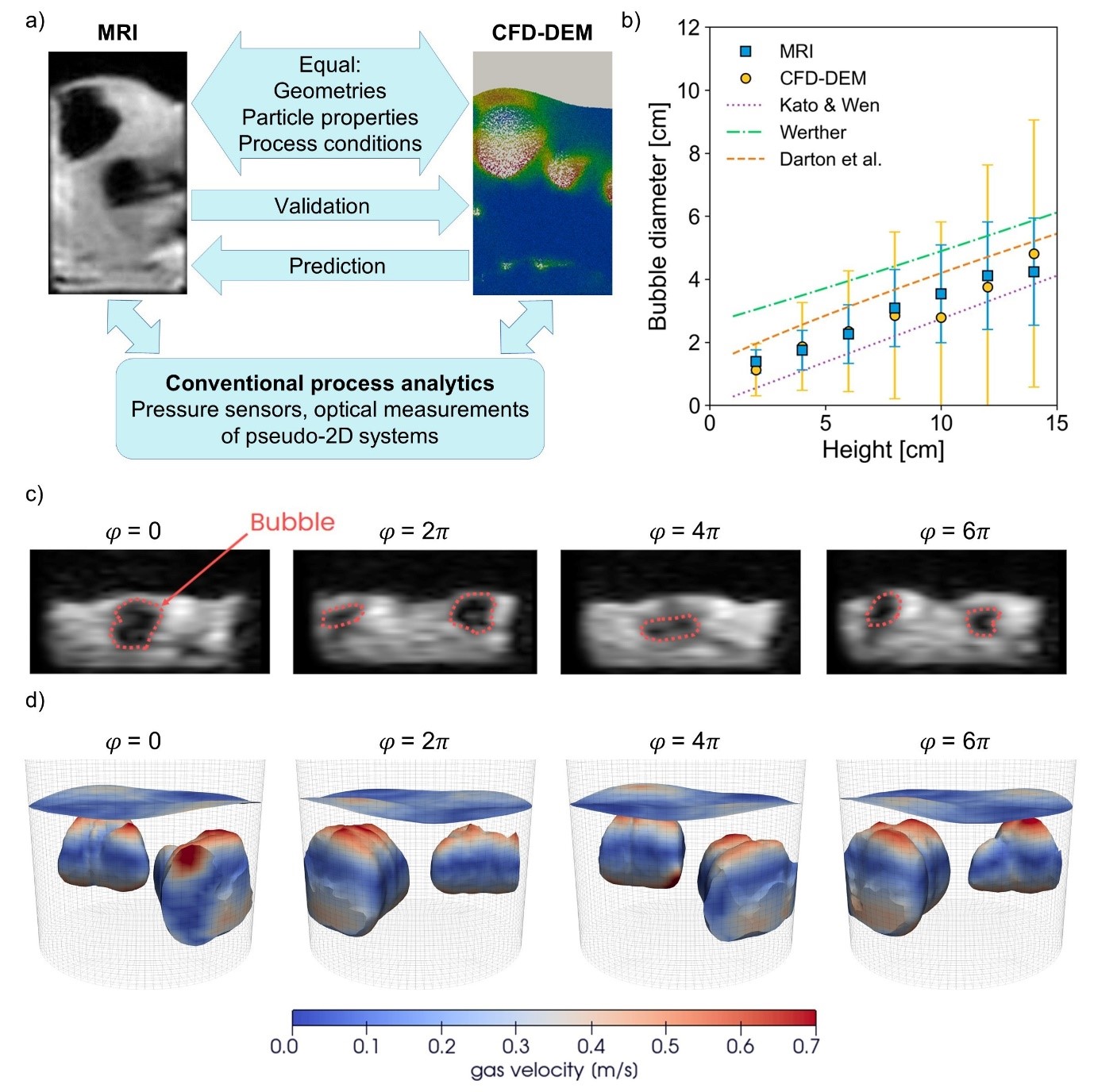

MRI measurements were successfully performed on vibrated and non-vibrated fluidized beds containing Geldart B and D particles (Figure 1a (Left)). Vertical slices through the center of the bed were acquired with a temporal resolution of 20 ms and a spatial resolution of 4 mm × 4 mm. Simulations of equivalent systems (Figure 1a (Right)) show good agreement with the experimental data in terms of bubble properties. The average bubble diameters derived from MRI measurements, CFD-DEM simulations, and established literature correlations show strong consistency (Figure 1b).

Additionally, as shown in previous publications [7,8], structured bubbling—a phenomenon observed at specific vibration frequencies and amplitudes and characterized by a repeating, highly predictable bubble pattern—was observed in both experiments and simulations. In pseudo-2D fluidized beds with glass beads, a triangular bubble pattern forms. The stability and regularity of the bubble pattern increase with decreasing particle size. Simulations further indicate that combining mechanical vibration with oscillating gas inlet flow further promotes stable pattern formation. MRI measurements demonstrate that structured bubbling can also be achieved through mechanical vibration in a 10 cm cylindrical fluidized bed containing Geldart B particles (Figure 1c). Simulations of cylindrical fluidized beds also show the formation of structured bubble patterns (Figure 1d). The characteristics of these patterns depend on the bed diameter and the application of mechanical vibration, gas flow oscillation, or a combination of both.

Figure 1: a) (Left) Instantaneous MRI snapshot of a 3D bubbling fluidized bed. (Right) Numerical CFD-DEM simulation of a system with comparable properties. b) Bubble diameter as a function of height from MRI measurements and CFD-DEM simulations of poppy seeds in a 10 cm diameter fluidized bed (initial bed height = 15 cm, Ugas,in/Umf = 1.6), compared with correlations from Kato & Wen [9], Werther [10], and Darton et al. [11]. c) Instantaneous MRI snapshots of a cylindrical 10 cm vibrated fluidized bed at successive vibration phases, showing a pattern that repeats every two phases. d) Isosurfaces of gas volume fraction at successive vibration phases, illustrating repeating bubble structures in a vibrated fluidized bed, obtained from CFD-DEM simulations

Acknowledgments

The project is financially supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under project number HE 4526/35-1.

References

[1] H. Perazzini, F.B. Freire, J.T. Freire, The Influence of Vibrational Acceleration on Drying Kinetics in Vibro-Fluidized Bed, Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification, 118 (2017), 124-130.

[2] C.P. McLaren, J.P. Metzger, C.M. Boyce, C.R. Müller, Reduction in Minimum Fluidization Velocity and Minimum Bubbling Velocity in Gas-Solid Fluidized Beds Due to Vibration, Powder Technology, 382 (2021), 566-572.

[3] A. Penn, T. Tsuji, D. O. Brunner, C.M. Boyce, K.P. Pruessmann, C.R. Müller, Real-time probing of granular dynamics with magnetic resonance, Science Advances, 3 (2017), e1701879.

[4] H.G. Weller, G.Tabor, H. Jasak, C. Fureby, A tensorial approach to computational continuum mechanics using object-oriented techniques, Computers in Physics, 12 (1998), 620–631.

[5] C. Kloss, C. Goniva, A. Hager, S. Amberger, S. Pirker, Models, algorithms and validation for opensource DEM and CFD‐DEM, Progress in Computational Fluid Dynamics, 12 (2012), 140-152.

[6] C. Goniva, C. Kloss, N.G. Deen, J.A.M. Kuipers, S. Pirker, Influence of Rolling Friction Modelling on Single Spout Fluidized Bed Simulations, Particuology, 10 (2012), 582-591.

[7] Q. Guo, Y. Zhang, A. Padash, K. Xi, T.M. Kovar, C.M. Boyce, Dynamically structured bubbling in vibrated gas-fluidized granular materials, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118 (2021), e2108647118.

[8] V. Francia, K. Wu, M.-O. Coppens, Dynamically structured fluidization: Oscillating the gas flow and other opportunities to intensify gas-solid fluidized bed operation, Chemical Engineering and Processing – Process Intensification, 159 (2021), 108143.

[9] K. Kato, C.Y. Wen, Bubble assemblage model for fluidized bed catalytic reactors, Chemical Engineering Science, 24 (1969), 1351-1369.

[10] J. Werther, Effect of gas distributor on the hydrodynamics of gas fluidized beds,

German Chemical Engineering, 1 (1978), 166–174.

[11] R.C. Darton, R.D. Lanauze, J.F. Davidson, D. Harrison, Bubble Growth Due To Coalescence in Fluidized Beds, Transactions of the Institution of Chemical Engineers, 55 (1977), 274–280.