2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(655c) Quantitative Measurements of Melanosome Dynamics Under Genetic Perturbations

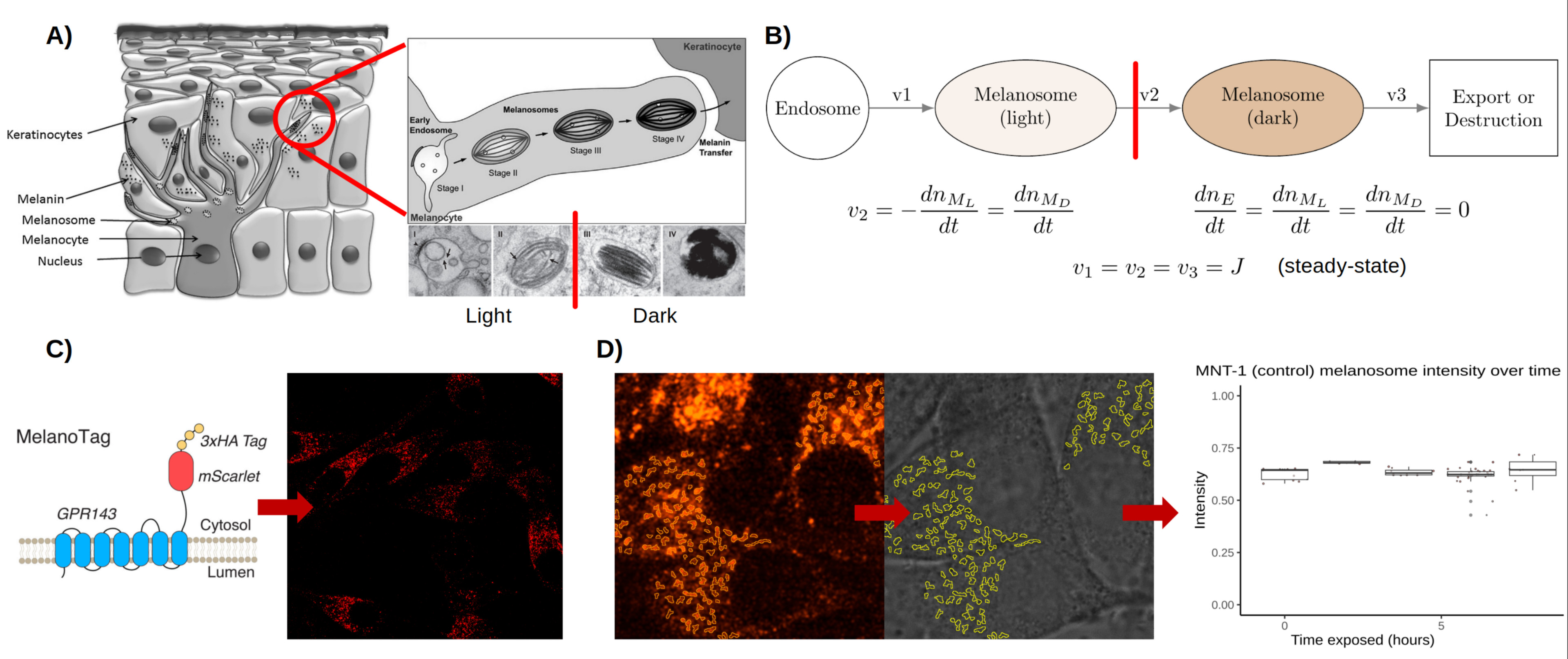

To this end, we genetically engineered an MNT-1 pigment cell line to stably express GPR143-mScarlet fusion protein. Similar to endogenous GPR143, we demonstrated that GPR143-mScarlet localizes on melanosome membrane and enables fluorescence based precise identification of melanosomes using confocal microscopy. Simultaneous, brightfield imaging is performed to measure absorbance which allowed us to infer relative melanin levels of identified melanosomes. By performing live-cell imaging of melanosomes over time, we estimated basal number of melanosomes as well as their melanin content. This direct observation of unperturbed (wild-type) MNT-1 cells reveals the “steady state” of a melanocyte’s “melanosome flux” as a constituent pigmentation. We envisioned that for given a genetic background melanosomes are in steady state where melanosomes are continuously progressing from distinct stages of maturation (Figure). Under this assumption, by transiently perturbing this steady state, melanosome flux and turnover time of the melanosome pool can be determined. To this end, we used Bafilomycin A1, which inhibits melanosome V-ATPase pumps and raises melanosome pH (5), driving the light melanosome pool to more mature, dark melanosomes. Following this chemical treatment, we performed imaging-based quantification of melanosome flux (change in melanosome number per time) and resident time (melanosome flux divided by basal melanosome number). Next, we employed the same approach under different genetic backgrounds to quantify impact of genes on melanosome flux and turnover rate. To this end, we introduced GPR143-mScarlet reporter system in MNT-1 cells with CRISPR deleted COMMD3, TYR genes as well as control-edited cells (cells that received a non-targeting guide RNA and Cas9; so, behave as wild-type cells). Loss of TYR and COMMD3 makes cells lose melanin and melanosomes appear predominantly in stage I/II compared to control-edited cells. Melanosome flux and resident time was quantified for TYR and COMMD3 knockout and control-edited cells following BafA1 treatment. This demonstrated the differential effects of a melanogenic gene’s role in contributing to the basal state melanosome pool, flux and its turnover rate. By applying this framework to several different novel genes, we will develop a novel understanding of the action of these genes in melanin synthesis and pigmentation pathways. Taken together, our work has broader implication for understanding melanin biology and for engineering new therapies for pigmentation disorders.

Figure. A) Melanocytes are located at the basal layer of the epidermis. They produce melanosomes, which undergo maturation in four stages from early endosome to fully melanized. Stages I and II can be considered “light” melanosomes, while III and IV are “dark”. B) The melanosome maturation pathway has multiple rates which equal each other when the melanocyte is at equilibrium. C) A genetically engineered reporter showing mScarlet fluorescent protein fused with melanosome-associated GPR143. D) Image analysis of melanosome loci via mScarlet signal allows quantification of light absorbance, a proxy for melanin abundance.

1. P. Meredith, T. Sarna, The physical and chemical properties of eumelanin. Pigment Cell Res 19, 572-594 (2006).

2. K. Ezzedine, V. Eleftheriadou, M. Whitton, N. van Geel, Vitiligo. Lancet 386, 74-84 (2015).

3. M. R. Laughter et al., The Burden of Skin and Subcutaneous Diseases in the United States From 1990 to 2017. JAMA Dermatol 156, 874-881 (2020).

4. G. Raposo, M. S. Marks, Melanosomes--dark organelles enlighten endosomal membrane transport. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 8, 786-797 (2007).

5. V. K. Bajpai et al., A genome-wide genetic screen uncovers determinants of human pigmentation. Science 381, eade6289 (2023).