2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(391o) Prompt-Based Equivalence Judgment of Manufacturing Process Models with Unknown Variables

In process industries, physical models play a crucial role in optimizing process control and operational conditions. These models are constructed by extracting and combining relevant variables and equations from the literature. However, the exponential growth of scientific literature has significantly increased the time and effort required for literature review. To address this issue, Kato and Kano have aimed to develop Automated Physical Model Builder (AutoPMoB), a system that automatically extracts information from literature databases and organizes it to build physical models [1]. AutoPMoB operates through five steps: 1) searching relevant literature, 2) standardizing document formats, 3) extracting essential information, 4) unifying terminology, and 5) constructing the desired model. Since variables and equations often differ in notation across sources, determining equivalence between equation groups is essential in Step 4. Two equation groups are considered equivalent if their relationships are algebraically identical and their variables denote the same physical quantities.

Kato et al. proposed an algorithm that determines the equivalence of equation groups based on two conditions: 1) the same variables are used, and 2) solving for any term yields the same result [2]. This algorithm accurately judged equivalence among 50 equation groups consisting of basic arithmetic operations, elementary functions, and derivatives. However, it assumes that all variable definitions are known and unified, which limits its applicability when variable definitions are unknown or inconsistent.

To overcome this limitation, this study proposes a method that uses a large language model (LLM) to simultaneously unify variable notations and assess the equivalence of equation groups. The LLM is prompted to evaluate equation group equivalence; this approach allows the model not only to determine whether the groups are equivalent but also to highlight their differences when present. The proposed method's effectiveness is evaluated using equation groups derived from documents on chemical processes.

Methods

We denote the two equation groups to be compared as A and B. Each comprises a variable set (VA1 and VB1) and an equation set (EA1 and EB1). A and B are judged equivalent if both VA1 and VB1 are equivalent and EA1 and EB1 are equivalent; otherwise, they are judged not equivalent.

The proposed method takes two equation groups (A and B) as input and produces the following outputs:

1. Whether the equation groups are equivalent (true) or not (false),

2. The magnitude of the differences between the equation groups, and

3. The differences if the magnitude is small.

This study defines the magnitude of the differences as the ratio of differing equations to the total number of equations in both groups. A difference is considered small when the value is less than or equal to 1/3. Therefore, the output depends on this ratio when the two equation groups are not equivalent: if it is 1/3 or less, the differences are output; otherwise, only "false" is output. This condition avoids an excessively long output when the differences are significant.

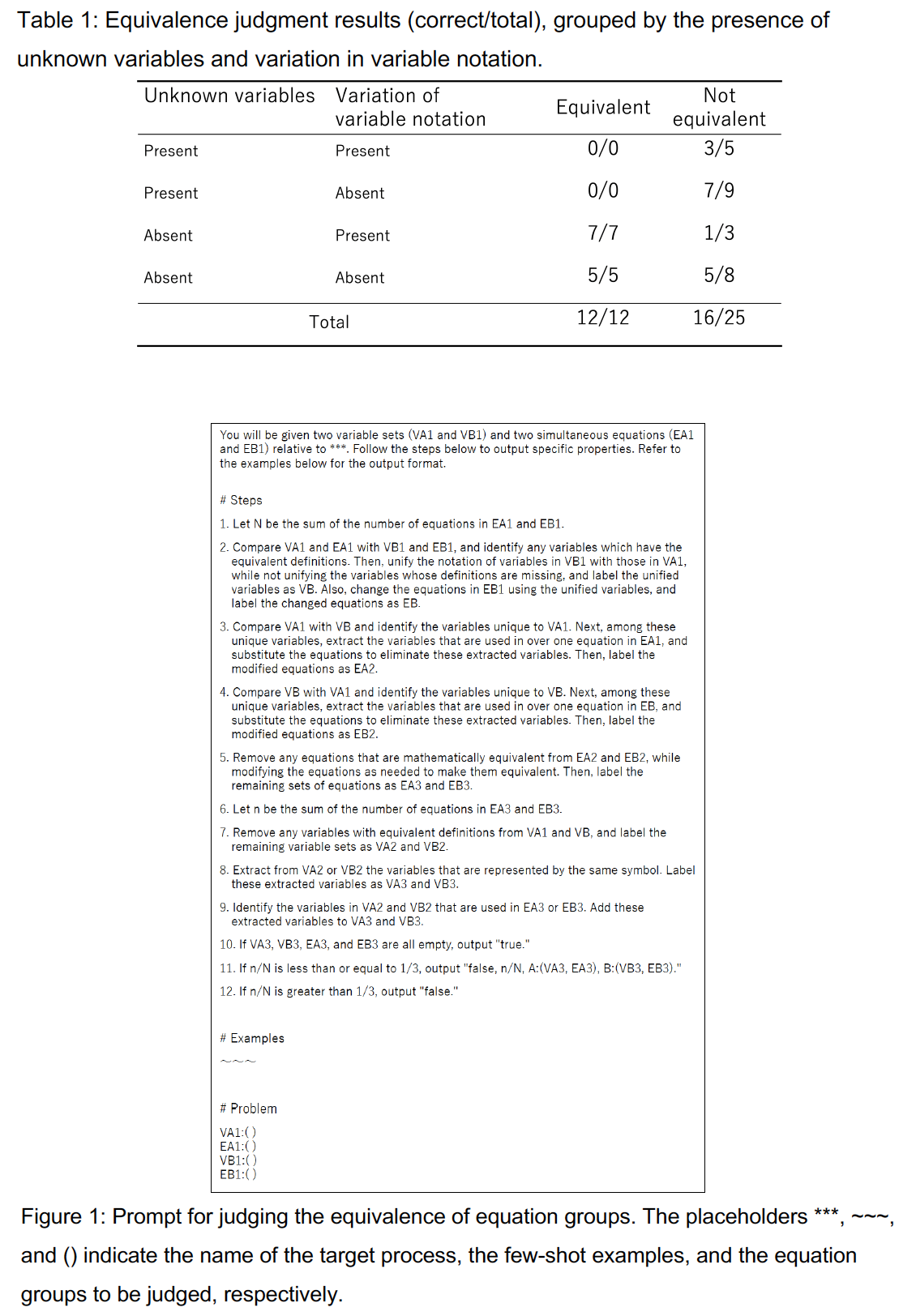

The prompt given to the LLM consists of four components: a problem description, a step-by-step procedure for judging the equivalence of equation groups, a few-shot prompt consisting of example tasks and their expected outputs, and the target equation groups to be judged. The problem description contains the target process name to support the judgment of equivalence between variables described using different expressions. The second component includes three instructions: unify the notation of equivalent variables, eliminate redundant variables and equations, and output the judgment result. In addition, few-shot prompting [3] is used to improve the model's performance and to specify the desired output format. Figure 1 shows the prompt used in this study.

Experiments

In this study, 37 pairs of equation groups were prepared based on a book on process control [4], papers on biodiesel production, and papers on a semiconductor raw material manufacturing process known as the Czochralski process. Among these, 12 pairs were equivalent, and 25 were not equivalent. The equations and variables were represented in LaTeX. For variables with unknown definitions, placeholders such as missing_1 and missing_2 were assigned according to the number of unknown variables in equation groups. Since the equation groups subjected to equivalence judgment in AutoPMoB are extracted from literature related to the target process, cases involving two models of entirely different processes were not considered.

We used OpenAI's gpt-4o-2024-11-20 as the LLM and set its temperature parameter to zero. The outputs generated by the LLM were compared with the correct answers for each pair of equation groups to verify whether they matched. Additionally, because the outputs include the process of handling variable and equation sets, we also evaluated whether these operations were performed correctly.

Results and Discussion

Table 1 summarizes the equivalence judgement results based on the presence of unknown variables and variable notation differences. Among the 37 pairs of equation groups, 28 pairs were correctly judged by the proposed method. All 12 equivalent pairs were correctly identified. The proposed method successfully unified the notation of equivalent variables when their variable definitions were written in similar words (e.g., "liquid density" and "density of liquid"). In some cases, the method also correctly judged the equivalence of equation groups that included unknown variables.

Nevertheless, the proposed method exhibited some errors: it failed to eliminate equivalent variables, eliminated unknown variables incorrectly, and miscounted the number of equations. These errors mainly occurred when equation groups contained unknown variables and variable notation variations, particularly when two unknown variables were present. Moreover, the method could not deal with certain types of notation differences that require more detailed information on the target process to determine equivalence between variables (e.g., "heat flux from the melt to the interface" and "heat flux from the melt and meniscus to the interface"). Such variables can be distinguished by referring to figures and tables related to the target process; thus, incorporating this information from the literature into the prompt may improve the accuracy of the judgment.

Conclusion

This study proposed a method for judging the equivalence of equation groups that include unknown variables and variation in variable notation. The proposed method successfully unified the notation of equivalent variables when their definitions were expressed using similar words. However, it exhibited errors in processing equation groups and was unable to handle certain types of notation differences that require more detailed information about the target process. Future work will focus on addressing these limitations by utilizing additional contextual information extracted from the literature.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP23K13595.

References

[1] Shota Kato and Manabu Kano. (2024). Prototype of Automated Physical Model Builder: Challenges and Opportunities. Computer Aided Chemical Engineering, Vol. 53, pp. 2839-2844.

[2] Shota Kato, Chunpu Zhang, and Manabu Kano. (2023). Simple algorithm for judging equivalence of differential-algebraic equation systems. Scientific Reports, Vol. 13, No. 11534.

[3] Tom B. Brown, et al. (2020). Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. arXiv:2005.14165.

[4] Dale E. Seborg, Thomas F. Edgar, Duncan A. Mellichamp, and Francis J. Doyle III. (2010). Process Dynamics and Control. Jhon Wiley & Sons, Inc.