2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(289a) Power and Mixing Time Analysis of Dual-Shaft, Turbine-Anchor Stirred Tanks for Newtonian Fluids in the Transitional Regime

Authors

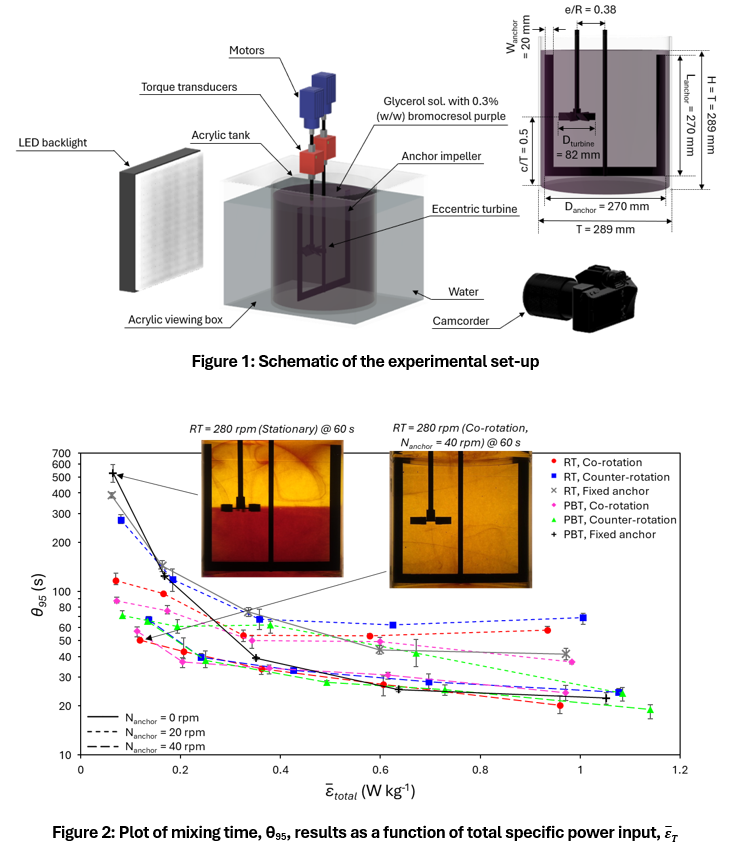

This study aims to advance the understanding of DSTA stirred tanks by visualising the mixing process using acid-base decolourisation. A pH indicator-based colour change method was employed to observe mixing time and dead zones, with acid or base added as a passive scalar and the process recorded using a Fujifilm X-T3 camcorder. Image processing techniques, following Cabaret et al. (2007) [1], were applied to calculate mixing time, θ95. A 90% v/v glycerol solution (μ ≈ 0.3 Pa s) containing 0.3% w/w bromocresol purple was used in a 19 L flat-bottomed tank (T = 289 mm) equipped with a top-driven anchor (Danchor = 270 mm) and an eccentric Rushton turbine (RT) or down-pumping pitched blade turbine (PBTd) (Dturbine = 82 mm), see Fig. 1. Power draw was measured using torque transducers (TorqSense SGR510). The anchor was either stationary, thus acting as a baffle, or operated at 20 or 40 rpm (Re = 123 and 245) while the eccentric turbine speed varied between 280 and 780 rpm (Re = 157-436). The effects of co-rotation (same direction) and counter-rotation (opposite direction) of the anchor and turbine on power draw and mixing performance were also investigated.

Results show that anchor rotation minimally impacted the power draw of the eccentric turbine with negligible differences between the fixed anchor and counter-rotation cases and a slight power reduction (up to 10.4%) in co-rotation. However, anchor power draw increased by up to 124% in counter-rotation compared to co-rotation as the flow from the turbine opposed anchor movement significantly. These findings align with the literature which show that the inner impeller strongly influences the anchor whilst the anchor has negligible effects on the inner impeller [2].

Regarding mixing performance, θ95 was significantly improved by anchor rotation for total specific power, ε‾ < 0.2 W kg-1 (Re < 250) where the turbine-generated flow was insufficient and, in some cases, led to dead zone formation (see Fig. 2). In this range, co-rotation was generally favoured, except for the PBTd at Nanchor = 20 rpm, and achieved a mixing time reduction of up to 57% compared to counter-rotation at the same impeller speeds. This trend aligns with coaxial stirred tank literature which similarly reports shorter mixing times for co-rotation [3]. At higher turbine speeds, however, the influence of anchor rotation diminished, particularly with the PBTd, which generated stronger axial flow and more effectively engaged the whole tank volume than the RT.

This study demonstrates that anchor rotation in DSTA stirred tanks can significantly improve mixing performance, particularly at low turbine speeds and when operated in co-rotation mode. At higher turbine speeds, the anchor's influence diminishes and impeller design (e.g., radial vs. axial) plays a more critical role in engaging the whole tank volume. Power draw analysis reveals minimal impact of anchor rotation on the eccentric turbine; however, anchor impeller power draw is significantly impacted by rotation mode and the speed of the turbine. These findings provide a foundation for understanding the complex nature of turbine-anchor impeller interactions and highlight the importance of proper impeller type and rotation mode selection.