2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(375f) Ni Metal and NiO Dissolution Kinetics in Acidic Media: Towards an Improvement of Ni-MH Battery Leaching

Authors

NiO(s) + 2H+(aq) → Ni2+(aq) + H2O, Eq. 1

Ni(s) + 2 H+(aq) + ½ O2(aq) → Ni2+(aq) + H2O, Eq. 2

We have previously shown that the yield limitation for Ni leaching in H2SO4 from BM Ni-MH is not due to the formation of a passivation layer: the dissolution limitation appears to be a surface chemical process [10]. NiO dissolution is much more complex than Ni metal because it involves an autocatalytic surface process with Ni(III) generation [11], [12], according to the reaction:

Ni(II)(s) + Ni(III)(s) → Ni(III)(s) + Ni2+(aq), Eq. 3

This autocatalytic dissolution process is highly dependent on several parameters, with kinetics hindered by thermal pretreatments [13] but enhanced by the addition of highly oxidative media, especially KMnO4 [14], [15].

In this work, we focused on a better understanding of the dissolution mechanisms of nickel powders in acid media, especially NiO, with the view of BM Ni-MH materials hydrometallurgical processing. We carried out leaching experiments on powders consisting of either pure NiO, pure Ni metal or a 1:1 mixture of NiO+Ni metal, or also an industrial BM-NiMH material. We used a 1 L thermostated reactor equipped with a four-blade Teflon stirrer and a torque meter (set at 230 rpm) filled with 500 mL of a H2SO4 aqueous solution, with pH and temperature regulated at 1.0 and 40 °C, and Ni dissolution yield calculated from acid consumption. The solid to liquid ratio was 2wt% for all experiments. A solution of KMnO4 (0.1 M) freshly prepared could be added with a syringe during experiment. NiO was synthesized from Ni(OH)2 powder at 400, 600 or 800 °C in a furnace under air atmosphere (7 L/min), to investigate the effect of thermal pretreatment [13]. The BM-NiMH from the SNAM group, also used in the previous work [1], [3], [10], was placed at 400°C under air flow (7 L/min) for 3 days in order to oxidize Ni metal into NiO to increase the NiO/Ni ratio in our material.

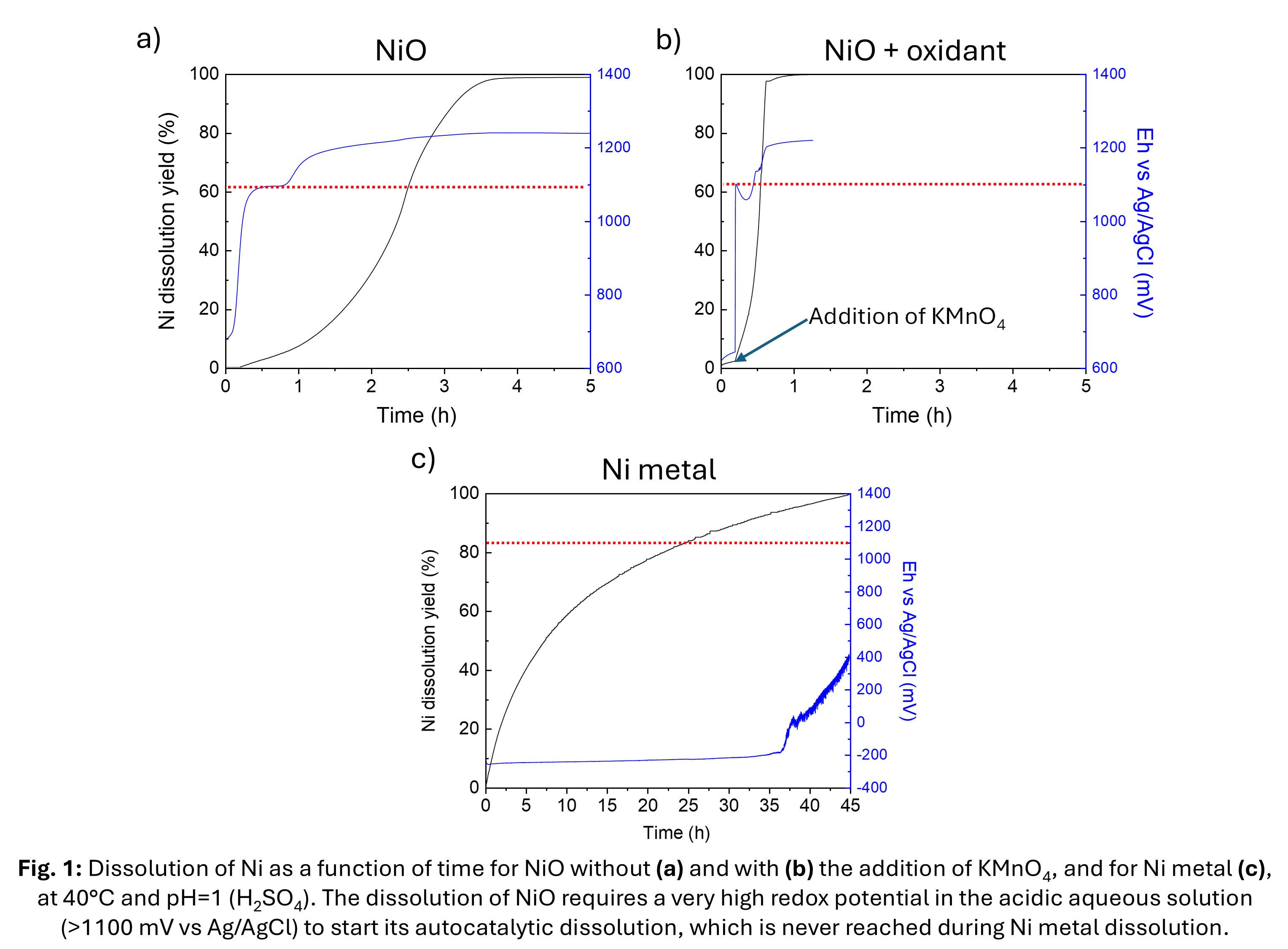

By recording the evolution of the redox potential during the leaching experiments, we were able to show that the autocatalytic dissolution of NiO only started when the redox potential was higher than 1100 mV vs. Ag/AgCl (Figure 1a,b). The autocatalytic dissolution of NiO could then be initiated by the addition of small amounts (1% of the initial NiO content) of a strong oxidant (KMnO4):

5Ni(II)(s) + MnO4–(aq) + 8H+→ 5Ni(III)(s) + Mn2+(aq) + 4H2O, Eq. 4

UV-visible analysis of MnO4– residual concentration provided information on the number of surface Ni sites converted to Ni(III) by the addition of KMnO4, with 16 times fewer active sites available when the NiO was synthesized at 800 °C instead of 400 °C, and 7 times fewer at 600 °C instead of 400 °C. The thermal pre-treatments at temperatures of 600 and 800 °C tend to deactivate the number of Ni(II) sites available for activation to Ni(III) sites, thus limiting NiO dissolution in BM Ni-MH.

Experiments were then carried out on Ni+NiO mixtures and BM Ni-MH powder. Tests with Ni metal+NiO mixtures show that the presence of Ni metal tends to inhibit NiO dissolution by maintaining the redox potential at the Ni/Ni2+ equilibrium (~–200 mV vs. Ag/AgCl, Figure 1c). Experiments with Ni-MH battery powders show that when most of the Ni metal is dissolved and the redox potential is no longer buffered by the Ni/Ni2+ equilibrium, the addition of KMnO4 greatly accelerates NiO dissolution resulting in a >99% Ni dissolution in 5 hours, compared to less than 30% Ni over equivalent time periods without the addition of KMnO4.

In conclusion, the presence of NiO can be advantageous for rapid nickel dissolution in Ni-MH batteries if a sufficiently high redox potential for dissolution (>1100 mV vs Ag/AgCl) is achieved. For example, the addition of a weaker oxidant, such as H2O2, can initially accelerate the dissolution of Ni metal, and then the addition of a stronger oxidant, such as KMnO4, can activate the dissolution of NiO. Other materials contain NiO and Ni metal, such as NMC Li-ion batteries [16] or perovskite solar cells [17] and this study may also help to understand some limitations of Ni recycling in such mixtures.

References

[1] M. Zielinski, L. Cassayre, P. Floquet, M. Macouin, P. Destrac, N. Coppey, C. Foulet, B. Biscans, A multi-analytical methodology for the characterization of industrial samples of spent Ni-MH battery powders, Waste Manag. 118 (2020) 677–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2020.09.017.

[2] I. Batsukh, M. Adiya, S. Lkhagvajav, S. Galsan, M. Gansukh, M. Batmunkh, Recovering Nickel‐Based Materials from Spent NiMH Batteries for Electrochemical Applications, ChemElectroChem 11 (2024) e202400135. https://doi.org/10.1002/celc.202400135.

[3] M. Zielinski, L. Cassayre, P. Destrac, N. Coppey, G. Garin, B. Biscans, Leaching Mechanisms of Industrial Powders of Spent Nickel Metal Hydride Batteries in a Pilot‐Scale Reactor, ChemSusChem 13 (2020) 616–628. https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.201902640.

[4] L. Cassayre, B. Guzhov, M. Zielinski, B. Biscans, Chemical processes for the recovery of valuable metals from spent nickel metal hydride batteries: A review, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 170 (2022) 112983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.112983.

[5] M. Takano, S. Asano, M. Goto, Recovery of nickel, cobalt and rare-earth elements from spent nickel–metal-hydride battery: Laboratory tests and pilot trials, Hydrometallurgy 209 (2022) 105826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2022.105826.

[6] K. Nut, On the dissolution behavior of NiO, Corros. Sci. 10 (1970) 571–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-938X(70)80051-8.

[7] K. Bhuntumkomol, K.N. Han, F. Lawson, The leaching behaviour of nickel oxides in acid and in ammoniacal solutions, Hydrometallurgy 8 (1982) 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-386X(82)90041-X.

[8] N. Vieceli, R. Casasola, G. Lombardo, B. Ebin, M. Petranikova, Hydrometallurgical recycling of EV lithium-ion batteries: Effects of incineration on the leaching efficiency of metals using sulfuric acid, Waste Manag. 125 (2021) 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2021.02.039.

[9] E.A. Abdel-Aal, M.M. Rashad, Kinetic study on the leaching of spent nickel oxide catalyst with sulfuric acid, Hydrometallurgy 74 (2004) 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2004.03.005.

[10] C. Laskar, A. Dakkoune, C. Julcour, F. Bourgeois, B. Biscans, L. Cassayre, Case-based analysis of mechanically-assisted leaching for hydrometallurgical extraction of critical metals from ores and wastes: application in chalcopyrite, ferronickel slag, and Ni-MH black mass, Comptes Rendus Chim. 27 (2024) 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5802/crchim.325.

[11] M.A. Blesa, P.J. Morando, A.E. Regazzoni, Chemical dissolution of metal oxides, CRC Press, Boca Raton, 1994. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781351070515.

[12] T. Grygar, J. Jandová, Z. Klı́mová, Dissolution reactivity of NiO obtained by calcination of pure and contaminated Ni-hydroxides, Hydrometallurgy 52 (1999) 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-386X(99)00008-0.

[13] C.F. Jones, R.L. Segall, R.St.C. Smart, P.S. Turner, Semiconducting oxides. The effect of prior annealing temperature on dissolution kinetics of nickel oxide, J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1 Phys. Chem. Condens. Phases 73 (1977) 1710. https://doi.org/10.1039/f19777301710.

[14] N. Valverde, Investigations on the Rate of Dissolution of Metal Oxides in Acidic Solutions with Additions of Redox Couples and Complexing Agents, Berichte Bunsenges. Für Phys. Chem. 80 (1976) 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/bbpc.19760800414.

[15] N.M. Pichugina, A.M. Kutepov, I.G. Gorichev, A.D. Izotov, B.E. Zaitsev, Dissolution Kinetics of Nickel(II) and Nickel(III) Oxides in Acid Media, 36 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020634014278.

[16] X. Zhu, S. Jiang, X.-L. Li, S. Yan, L. Li, X. Qin, Review on the sustainable recycling of spent ternary lithium-ion batteries: From an eco-friendly and efficient perspective, Sep. Purif. Technol. (2024) 127777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.127777

[17] F. Meng, J. Bi, J. Chang, G. Wang, Recycling Useful Materials of Perovskite Solar Cells toward Sustainable Development, Adv. Sustain. Syst. 7 (2023) 2300014. https://doi.org/10.1002/adsu.202300014.