2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(454e) Mxene@MOF Composite Mixed Matrix Membranes for the Removal of per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Wastewater

Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are persistent emerging water contaminants and their removal from water bodies is a rigorous challenge. In this work, engineered nanocomposite (DMMIL) was synthesized via in-situ growth of iron-based metal-organic framework (MOF) in polydopamine-coated MXene (PD@Ti3C2Tx) sheets. The synthesized DMMIL was incorporated in cellulose acetate (CA) polymer to fabricate mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) (DMMIL/CA) and achieve enhanced removal efficiency of PFAS. The best membrane (50%DMMIL/CA) exhibited 1.42-fold enhanced water flux and 1.65-fold enhanced perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) rejection compared to the pristine CA membrane. The fouling test was run for cycles of PFOA filtration followed by cleaning with DI water, and the produced membranes showed up to 68% of flux recovery after 5 cycles. The membrane's effectiveness in removing both long- and short-chain PFAS was tested in synthetic and real wastewater.

Introduction:

The advancement in industrialization has elevated the levels of toxic pollutants in various water bodies to unprecedented levels and has introduced many new contaminants that are very harmful to the environment, ecosystem and human life [1]. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are emerging contaminants known for their persistent nature, strong carbon-fluorine bond, and harmful health effects, and hence their removal is a great challenge [2]. Research has shown their harmful effects on both humans and animals [3]. Researchers are testing various treatment technologies to remove PFAS from water and landfill leachates [4]. Membrane science is considered a sustainable water treatment technology. Especially nanofiltration (NF) and reverse osmosis (RO), have received growing attention for their effectiveness in removing PFAS [5]. NF and RO membranes reject PFAS primarily through steric exclusion (based on size) and solution-diffusion, resulting in challenges such as fouling, flux decline and high cost. Incorporating nanoparticles in the polymeric membranes can enhance the membrane’s performance by improving the selectivity of pollutants, enhancing water permeance and flux, increasing its durability and stability, and increasing its antifouling properties [6].

In this research, we synthesize a novel Polydopamine coated MXene and MOF(Fe) based nanocomposite material by using in-situ growth method. The synthesized material is incorporated in the cellulose acetate membrane using the NIPS methods for the effective removal of PFAS from the water. The properties of nanocomposite material and membranes are accessed by using different characterization techniques and performance is measured in synthetic and real wastewater systems.

Methods and Methodology

i). Synthesis of nanocomposite material and membrane

MXene was synthesized by adding 0.8 g of LiF into 10ml of 9M HCl. After 5 min of stirring, 0.5g of Ti3AlC2 was added slowly and the solution was left for stirring at 35ºC for 28 hours. Then, it was centrifuged at 9000 rpm and washed with DI water several times until the pH reached 5, followed by 1-hour sonication to obtain delaminated nanosheets of Ti3C2Tx. In the second step, dry Ti3C2Tx powder was added into a mixture of tris-buffer solution (20 mM; pH=8.5) and absolute C2H5OH (4:1 v/v)), and bath-sonicated for well-dispersion. After that, Dopa-HCl was added and stirred for 24 h at room temperature. Finally, PD@Ti3C2Tx was obtained by filtering and washing several times with DI water.

PD@Ti3C2Tx was used to prepare the nanocomposite material with the in-situ growth of MOF(Fe) into the PD@Ti3C2Tx sheets. PD@Ti3C2Tx was dispersed in the DI water and 10mmol of Iron nitrate solution in the round bottom flask by using the reflux setup. 9 mmol of trimeric acid was added slowly in the flask. The mixture was stirred at 95 ºC for 12 hrs and filtered by using the vacuum filtration setup. Later it was dried and stored. Four different compositions of nanocomposite were prepared. (i) 10%DMMIL (10%PD@Ti3C2Tx/90%MOF); (ii) 20%DMMIL (20%PD@Ti3C2Tx/80%MOF); (iii) 50% DMMIL (50%PD@Ti3C2Tx/50%MOF); (iv) 80%DMMIL (80%PD@Ti3C2Tx/20%MOF).

The nanocomposite membranes were prepared by NIPS method using 4% of nanocomposite and 20% of CA. The nanomaterial was first dissolved in the solvent using bath sonicator then the polymer is dissolved by stirring overnight for uniform mixture followed by degassing in vacuum oven.

ii). Characterizations and performance

The functional groups and crystal structure of all nanomaterials were accessed by using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and (X-ray diffraction) XRD. To study the morphology and elemental composition of synthesized material, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) were used. Zeta potential was performed to test the electronegativity of the material.

FTIR, and SEM were used to examine the functional group and microscopic cross-sectional morphology of membranes. The zeta potential of membranes will be used to test their electronegativity at acid, basic, and neutral conditions. Static and dynamic water contact are used to check the hydrophilicity of membranes. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) was also conducted. The porosity, mechanical strength, and leaching of the membranes were also checked.

iii). Filtration experimentation

Filtration experiments were performed using deionized (DI) water to check the permeability. Polluted water is filtered through the produced membranes by using (i) synthetic Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) solution, (ii) synthetic mixed solution of PFOA, perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA )and perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA), and (iii) real wastewater samples. All membrane filtration tests were conducted in a dead-end ultrafiltration setup at room temperature under a constant pressure of 3.5 bar. The concentrations of PFAS in the permeate were quantified using a liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system. Fouling resistance of the membranes was evaluated over five filtration cycles

Results

i). Characterizations

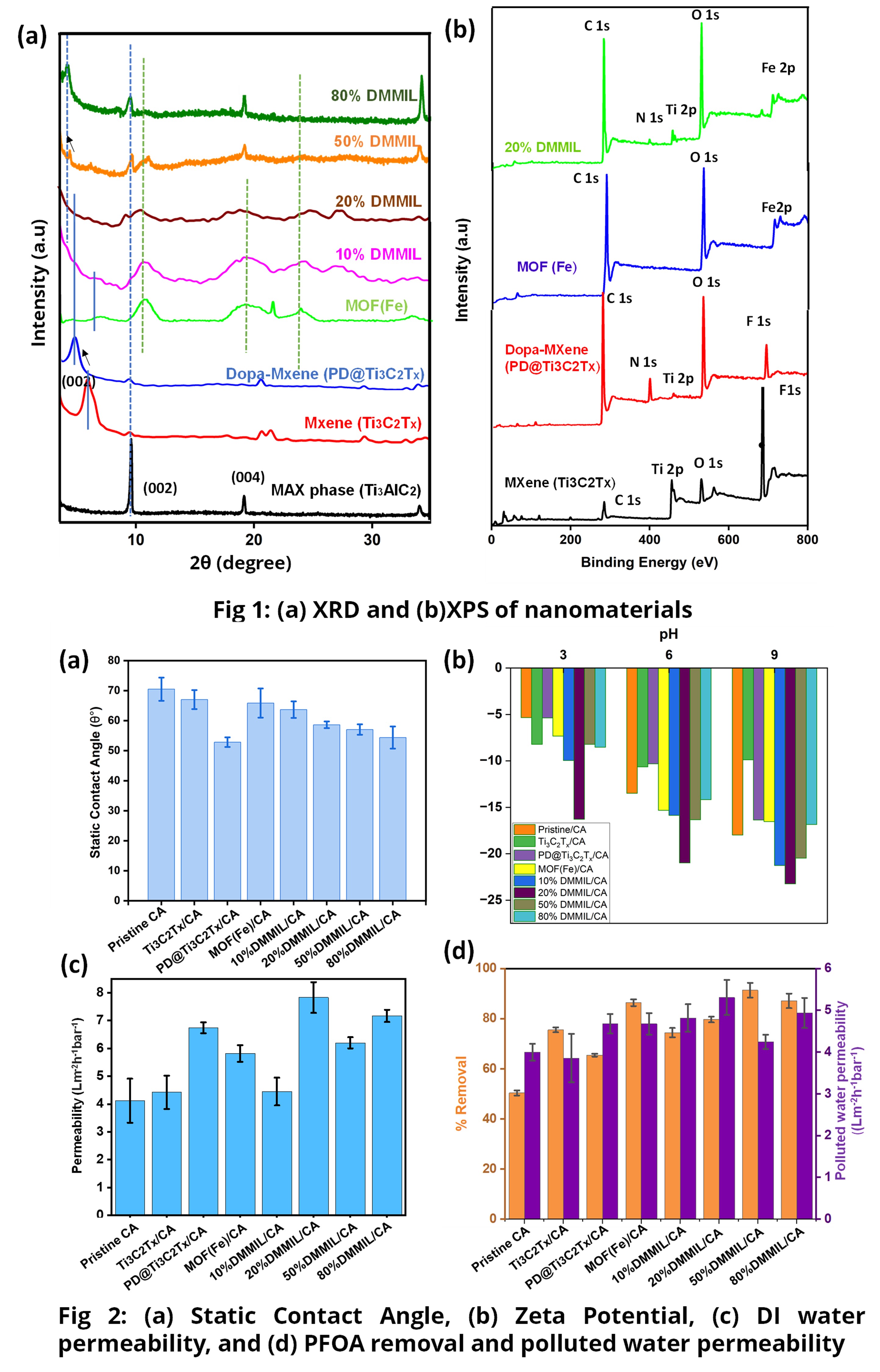

The XRD and XPS are shown in Fig 1 (a and b). The shift of (002) peak in PD@Ti3C2Tx indicates an increase in interlayer spacing. The FTIR is used to confirm the functional groups. MOF (Fe) shows a peak around 1700 cm-1 due to C=O stretching and a peak at 1440 cm-1, demonstrating the presence of C-C stretching vibration in the aromatic ring. While the peak at 1370 cm-1 and 750 cm-1 demonstrates the C-H functionality [7], [8]. The Ti3C2Tx modification with polydopamine can be confirmed by the peak aroused at ~1500 cm-1 due to the C-C stretching, at 1580 cm-1, 1650 cm-1 and 1990 cm-1 because of N-H bending of aromatic secondary amine and the peak at 1270 cm-1 due to the C-N stretching of the benzenoid ring [9], [10]. All compositions of synthesized nanocomposite material show the functional groups from both MOF and PD@Ti3C2Tx.

Cross-sectional SEM images of the membranes showed a finger and sponge-like structure. Membranes are asymmetric showing a very dense structure towards the top and comparatively wider channels towards the bottom.

ii). Filtration experiments

All the MMMs exhibited enhanced water permeation compared to the pristine CA membrane. Among the four DMMIL/CA MMMs, the 20%DMMIL/CA membrane demonstrates the highest permeation of 7.8 Lm-2h-1bar-1, 1.8 times (80.3%) higher than the pristine, followed by the 80% DMMIL/CA and 50% DMMIL/CA as shown in Fig 2(c). Both hydrophilicity and porosity of membranes contributed towards this enhanced permeance.

50%DMMIL/CA membrane achieved the highest removal rate of 91.4% among all the membranes, followed by the 80%DMMIL/CA membrane with a removal rate of 89% as shown in Fig 2(d). This performance is mainly attributed to the high negative zeta potential of these membranes. The mechanism followed here for the removal of PFOA is mainly charge exclusion and hydrophobic interactions.

When PFOA was filtered with other short-chained PFAS (PFHpA and PFHxA), the membrane exhibited a similar flux of 4.3 Lm-2s-1bar-1 with a standard deviation of 0.2, for polluted water (with three PFAS) as it did for water containing only PFOA. The membrane also showed good removal of short-chained PFAS. In the real wastewater system, the 50%DMMIL/CA membrane showed good removal of PFAS along with other organic and inorganic pollutants.

Conclusion

In this study, a PD@Ti₃C₂Tₓ-MOF(Fe) (DMMIL) nanocomposite was synthesized. Four nanocomposite compositions were incorporated into mixed-matrix membranes (MMM), demonstrating a typical asymmetric structure with a dense skin layer and sponge-like cross-section. Among the fabricated membranes, 20% DMMIL/CA exhibited the highest negative charge across all tested pH conditions (3, 6, and 9), while 80% DMMIL/CA showed the greatest hydrophilicity (WCA = 54°). The 20% DMMIL/CA membrane also achieved the highest DI water permeability (7.8 Lm-2h-1bar-1) due to its high porosity (ε = 62%) and good hydrophilicity (WCA = 58.6°). Regarding PFOA removal efficiency, the 50% DMMIL/CA membrane performed best, achieving around 92%. Simultaneous removal of long and short-chained PFAS and the real wastewater studies demonstrate the reduction in removal potential due to the combined effect of all pollutants. Additionally, the membranes demonstrated good antifouling performance over five filtration cycles, with minimal material leaching, confirming their stability.

These findings highlight the promising potential of DMMIL-based nanocomposite membranes for water and wastewater treatment applications, particularly in PFAS removal. However, real wastewater studies suggest that pre-removal of organic matter and competing ions could further enhance PFAS removal efficiency. Future research should focus on optimizing pre-treatment processes to improve selectivity and performance in complex water matrices and post-treatments to destroy and permanently remove PFAS from the environment.

Reference

[1] S. Ding, L. Zhang, Y. Li, and L. Hou, “Engineering a High-Selectivity PVDF Hollow-Fiber Membrane for Cesium Removal,” Engineering, vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 865–871, Oct. 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.eng.2019.07.021.

[2] Xiahilim, “Researchers are struggling to assess the dangers of nondegradable compounds used in clothes, foams and food wrappings.,” Nature, vol. 566, p. 4, 2019.

[3] L. Jane L Espartero, M. Yamada, J. Ford, G. Owens, T. Prow, and A. Juhasz, “Health-related toxicity of emerging per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances: Comparison to legacy PFOS and PFOA,” Sep. 01, 2022, Academic Press Inc. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113431.

[4] D. Banks, B. M. Jun, J. Heo, N. Her, C. M. Park, and Y. Yoon, “Selected advanced water treatment technologies for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances: A review,” Jan. 16, 2020, Elsevier B.V. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2019.115929.

[5] T. Lee, T. F. Speth, and M. N. Nadagouda, “High-pressure membrane filtration processes for separation of Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS),” Mar. 01, 2022, Elsevier B.V. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.134023.

[6] M. Khraisheh, S. Elhenawy, F. Almomani, M. Al-Ghouti, M. K. Hassan, and B. H. Hameed, “Recent progress on nanomaterial-based membranes for water treatment,” Dec. 01, 2021, MDPI. doi: 10.3390/membranes11120995.

[7] F. Zhang, J. Shi, Y. Jin, Y. Fu, Y. Zhong, and W. Zhu, “Facile synthesis of MIL-100(Fe) under HF-free conditions and its application in the acetalization of aldehydes with diols,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 259, pp. 183–190, Jan. 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2014.07.119.

[8] R. Nivetha et al., “Highly Porous MIL-100(Fe) for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) in Acidic and Basic Media,” ACS Omega, vol. 5, no. 30, pp. 18941–18949, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c02171.

[9] S. Chen and H. Liu, “Self-reductive palladium nanoparticles loaded on polydopamine-modified MXene for highly efficient and quickly catalytic reduction of nitroaromatics and dyes,” Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp, vol. 635, Feb. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.128038.

[10] B. Wan et al., “Water-dispersible and stable polydopamine coated cellulose nanocrystal-MXene composites for high transparent, adhesive and conductive hydrogels,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 314, Aug. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.120929.