2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(234f) Multi-Agent Optimisation of Adoption Behaviours in Biofuel Supply Chains

Authors

Effective coordination across supply chain (SC) levels, from operational to strategic, is crucial for enhancing the comprehensiveness of process and energy system models. This integration is particularly relevant for models that incorporate evolving policy decisions and technological advancements, such as those in biofuel SCs [1]. Biofuels offer a vital alternative to fossil fuels by using renewable feedstocks and reducing net carbon dioxide emissions [2]. Despite their potential to help achieve climate goals, the complex interactions among stakeholders—raw material suppliers, processing plants, and consumers—and the influence of government policies, like subsidies, often lead to unclear or oversimplified outcomes in conventional biofuel SC models.

Several studies have investigated the optimisation of biofuel supply chains (SCs) to achieve sustainability goals [3-5]. While some have examined the impact of technological options on SCs, none have specifically addressed the effects of biorefinery process details on biofuel adoption. Computational methods, such as agent-based modelling, have been employed to manage the complexities and uncertainties of biofuel SCs, particularly the feedback relationships between agents [1]. The most comprehensive studies [1, 6] have proposed agent-based models to simulate biofuel adoption by stakeholders in response to government policies, including varying subsidy levels and the social and environmental impacts of products.

This investigation employs a multi-scale agent-based model to represent the organisational structure of integrated SCs. These multi-dimensional features enable simultaneous assessment and optimisation, especially in exploring optimal adoption in biofuel-driven processes and energy systems. The framework advances decision-making beyond previous studies by incorporating decisions at the firm level, through adjustments to intra-organisational planning, and at lower levels, by including biorefinery process variables.

Methodology

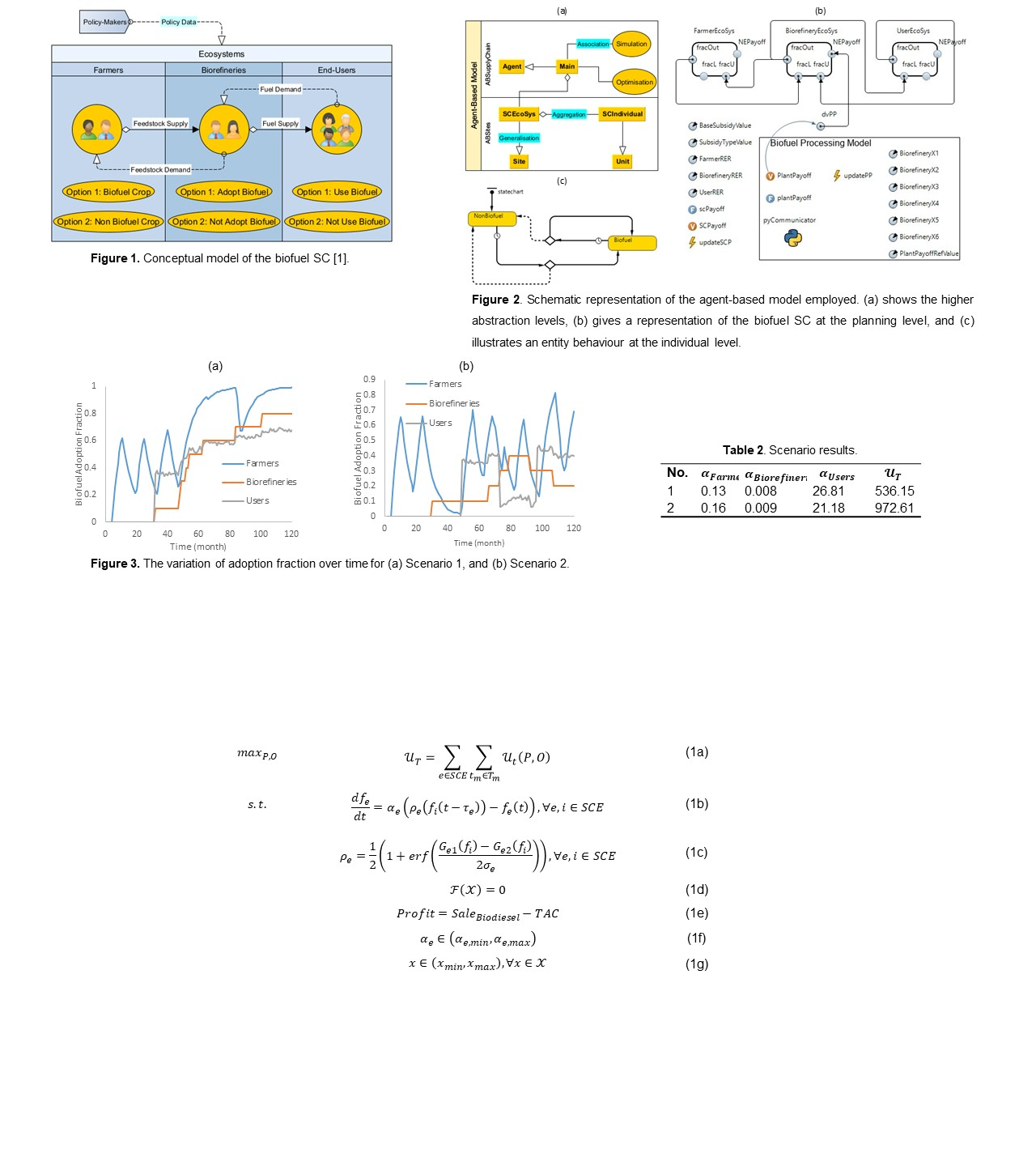

This study models a biofuel SC as a network of interconnected computational ecosystems characterised by distributed and asynchronous decision-making and incomplete information. As shown in Figure 1, the system includes various actors consisting of farmers, biorefineries, and end-users, each having binary choices concerning biofuel adoption.

The biofuel adoption problem is formulated based on Equation 1. The problem is defined with planning decision variables (P) that include re-evaluation frequencies, and operational-level decisions (O) that involve adjusting biorefinery process parameters. Both levels are subject to equality, inequality, and implicit constraints. The objective function, Equation 1(a), represents the total utility of all ecosystems (SCE) across all sample periods (Tm), determined by the individual payoff functions. Notably, the biorefinery’s overall profit is used to scale the respective ecosystem payoff.

Constraint 1(b) monitors the SC behaviour at the aggregate level, influenced by the fraction of actors adopting biofuels (fe), their re-evaluation frequencies (αe), and information delays (τe).

The preference probability of biofuel adoption (ρe), as expressed in Constraint 1(c), is influenced by the respective option’s payoff. Two utility functions, and are defined for adopting or not adopting biofuels, respectively. These functions are affected by adoption fractions within the same tier and neighbouring ecosystems as well as the utility function’s measurement uncertainties (σe) [1].

Constraint 1(d) captures the production process behaviour through a nonlinear biorefinery model [7]. This relates the final product flow rate, purity, temperature, and heat duty requirement to the input process variables and parameters, including feed and solvent flow rates and temperatures along with water mass flow and the boiler pressure. Constraint 1(e) determine the plant’s overall profit based on the final product sale (SaleBiodiesel) and the total annual costs (TAC). Finally, Constraints 1(f) and 1(g) observe the lower and upper bounds on planning and operational decision variables.

A multi-agent system involves various actors performing multiple tasks, choosing resources based on perceived benefits. Due to these features, agent-based modelling in the AnyLogic development environment (ver. 8.9.4) [8] is used. The framework materialises a two-level hierarchy, as demonstrated in Figure 2. The domain model, shown in Figure 2(a), connects two broad modules: the supply chain module, which represents the overall structure of supply networks, and the site module, which includes elements like Unit and Site to capture individual or ecosystem details. The specialised model, illustrated in Figure 2(b), supports a high-abstraction model for biofuel adoption, involving three interconnected agents representing SC partners. The framework reflects the two-option behaviour of each system component, as depicted in Figure 2(c). The process model is implemented in Python using Pyomo (ver. 6.8.0) [9] and linked to the main platform via the Pypeline interface.

Results and Implications

A biofuel SC case study is based on previous research [1], also incorporating specific models and parameters for biofuel plants [7]. The optimisation problem considers two scenarios, highlighting the impacts of decision-level integrations and non-equilibrium dynamics on SC performance. These scenarios are distinguished by different subsidy types: constant and periodic policies. Both subsidy types have a similar base value (5), but the periodic policy changes to zero every two years [1].

The dynamic adoption problem is optimised using the OptQuest solver over 10 years with monthly samples. The ecosystem includes 1000 farmers, 10 biorefineries, and 30,000 users. Optimisation uses up to 1000 generations for convergence. Raw material and biodiesel prices, and ecosystem parameter bounds, remain consistent with prior studies [1, 7]. Experiments run on an Intel Xeon E5-2620 CPU with 128GB RAM.

Figure 3 illustrates the predicted adoption fraction over time for various scenarios. Additionally, Table 1 lists the supply chain decision variables and utility function values. In what follows, a detailed analysis of the findings is provided. Concerning the first scenario, Figure 3(a) shows a late surge in adoption followed by a drop, especially among farmers. In this setting, integrating processing plants improves system’s visibility but reduces actor participation. Furthermore, the framework integrates raw material supply from farmers with biofuel demand from users. In later stages, increased feedstock supply leads to local competition among farmers, negatively impacting their adoption rates. This decline has cascading effects on downstream actors, as illustrated in Figure 3(a).

Figures 3(a) and 3(b) show that a constant subsidy leads to higher overall adoption fractions, indicating its effectiveness in promoting consistent adoption. However, the periodic subsidy leads to a higher total utility value, owing to the frequent changes in the adoption patterns. Therefore, a trade-off between subsidy types and values exists, potentially guaranteeing a less oscillating adoption and higher payoffs.

Figures 3(a) and 3(b) illustrate that a constant subsidy results in higher overall adoption fractions, demonstrating its effectiveness in promoting steady adoption rates. This consistency is beneficial for maintaining a stable supply chain. On the other hand, the periodic subsidy, which fluctuates over time, leads to a higher total utility value due to the dynamic changes in adoption patterns. These frequent shifts can optimise resource allocation and utilisation, enhancing overall system performance.

The analysis reveals a trade-off between the two subsidy types. While a constant subsidy promotes consistent adoption, a periodic subsidy can yield higher payoffs by leveraging the variability in adoption rates. This trade-off suggests that a balanced approach, potentially combining elements of both subsidy types, could achieve a more stable adoption rate while maximising utility. Such a strategy would help mitigate the oscillations in adoption and ensure higher overall payoffs, benefiting all stakeholders in the supply chain.

Overall, Figure 3 and Table 1 show that biofuel SC models should consider process details, policy types, and information delays to accurately depict system behaviour and improve policy implementation success.

Conclusion

This work introduces an agent-based framework to examine the integration of process plant constraints and dynamic interactions among multiple actors in process and energy SCs. The model uses a bilevel structure to address general and specialised cases, such as biofuel SCs. Agent technology captures interdependencies and feedback among actors, providing a comprehensive representation of SC dynamics and revealing emergent system-level behaviours not evident in simpler models.

A biofuel SC case study demonstrates the framework's capability, involving farmers, biorefineries, and end-users in a dynamic network. The study seeks an optimal collective adoption pattern using a two-option strategy at individual levels. Results indicate that integrated decision-making offers a more realistic and insightful biofuel SC model. The findings highlight the need to move beyond the traditional view of biorefineries as sole decision-makers. Future research should enhance individual payoff function representation and focus on complex subsidy types and environmental sustainability measures. A holistic and dynamic modelling approach can help researchers and decision-makers better understand biofuel SCs and develop effective strategies for this emerging industry.

References

- D. Agusdinata, S. Lee, F. Zhao, W. Thissen. Simulation modeling framework for uncovering system behaviors in the biofuels supply chain network. SIMULATION 90 (2014):1103–1116 https://doi.org/10.1177/0037549714544081

- D. Kumari, R. Singh. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic wastes for biofuel production: a critical review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 90 (2018):877-891 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.03.111

- S. Shirazaki, M. S. Pishvaee, M. A. Sobati. Integrated supply chain network design and superstructure optimization problem: a case study of microalgae biofuel supply chain. Computers & Chemical Engineering 180 (2024): 108468 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2023.108468

- M. Umar, M. Tayyab, H. R. Chaudhry, C.-W. Su, N. Navigating epistemic uncertainty in third-generation biodiesel supply chain management through robust optimization for economic and environmental performance. Annals of Operations Research (2023): 1-40 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-023-05574-1

- S. Bairamzadeh, M. Saidi-Mehrabad, M. S. Pishvaee. Modelling different types of uncertainty in biofuel supply network design and planning: A robust optimization approach. Renewable energy 116 (2018): 500-517 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2017.09.020

- P. Yang, X. Cai, X. Hu, Q. Zhao, Y. Lee, M. Khanna, Y.R. Cortés-Peña, J.S. Guest, J. Kent, T.W. Hudiburg, E. Du. An agent-based modeling tool supporting bioenergy and bio-product community communication regarding cellulosic bioeconomy development. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 167 (2022): 112745 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.112745

- L. Zhou, M. Pan, J.J. Sikorski, S. Garud, L.K. Aditya, M.J. Kleinelanghorst, I.A. Karimi, M. Kraft. Towards an ontological infrastructure for chemical process simulation and optimization in the context of eco-industrial parks. Applied Energy 204 (2017): 1284-1298 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.05.002

- A. Borshchev. Multi‐method modelling: AnyLogic. (2014): 248-279 In: Discrete‐Event Simulation and System Dynamics for Management Decision Making. Ed: S. Brailsford, L. Churilov, B. Dangerfield John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (2014) https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118762745.ch12

- William E. Hart, Jean-Paul Watson, David L. Woodruff. Pyomo: modeling and solving mathematical programs in Python. Mathematical Programming Computation 3(3) (2011): 219-260 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12532-011-0026-8