2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(619b) Molecularly Imprinted Photonic Polymer for 11-Keto Testosterone Hormone Detection in Aqueous Samples

Authors

Endocrine disruptors, including hormones and hormone-mimicking compounds, have emerged as significant water contaminants in recent years. These contaminants, originating from pharmaceuticals, wastewater discharge, and livestock farming, can easily accumulate in living organisms.[1, 2] Even at trace amount, they can lead to health issues in both animals and humans including hormonal imbalances, fertility issues, metabolic disorders, developmental and reproductive abnormalities, behavioral changes, and increased cancer risks (e.g., breast, prostate, and thyroid).[2–4] Among these endocrine-active compounds, 11-keto testosterone (11-kT) is a naturally occurring androgenic hormone, primarily found in fish, where it acts as the most potent androgen, and is also widely distributed across the animal kingdom.[5] In humans, it plays a dominant role as a bioactive androgen during adrenarche and premature adrenarche in children.[6] Given its potential biological effects and widespread presence in aquatic environments, it is highly important to monitor 11-kT levels in water samples for assessing its effect on both wildlife and human health.

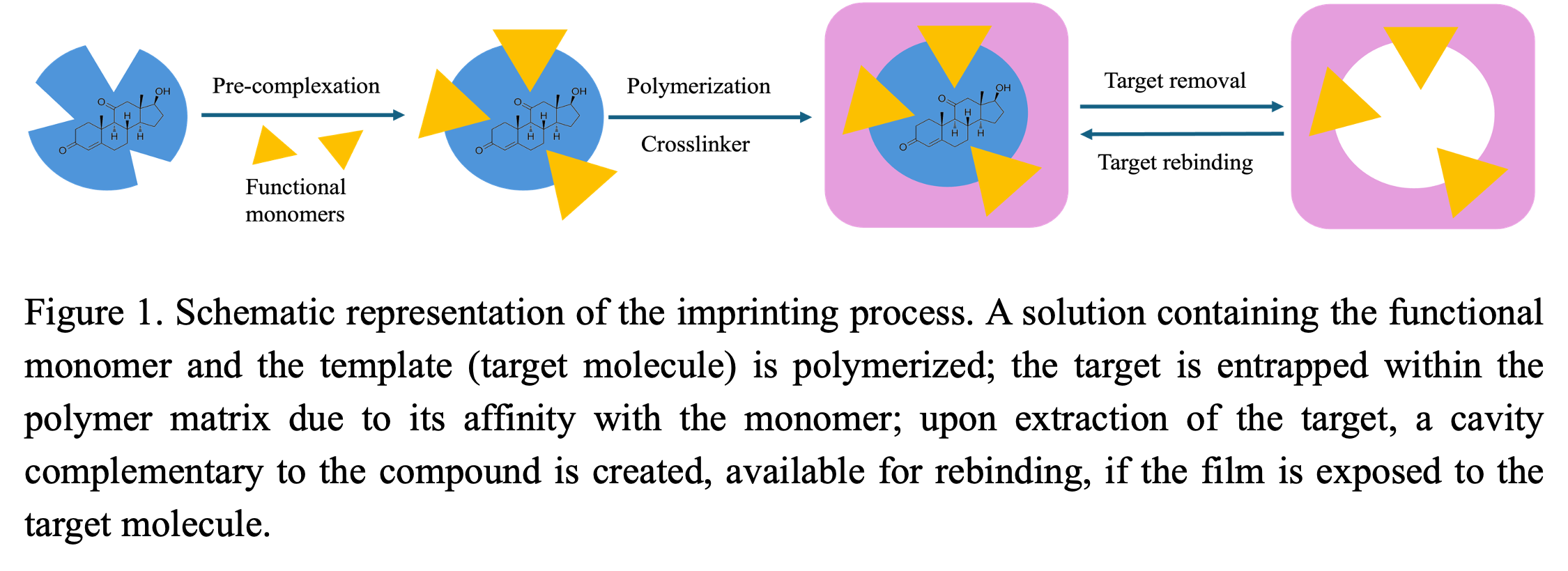

In this research, a Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) photonic sensor was synthesized for 11-kT hormone detection and its performance was tested in water samples. Among various sensing technology for environmental quality monitoring, Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) based sensing is one of the most promising approaches due to its high selectivity, durability, and cost-efficiency. The MIPs were synthesized in the void spaces of a colloidal crystal, which led to their photonic properties. The fundamental principle of molecular imprinting involves preparing a polymer in the presence of a target analyte, forming specific binding sites in the polymer as cavities that precisely complement the size and structure of the target molecule. These MIPs function as synthetic receptors creating highly specific and stable binding sites for the targeted analyte. Upon incubation in solutions containing the target molecule, the polymer shows a peak in the visible range of its reflectance spectrum, and its location depends on the degree of binding of the analyte to the imprinted sites.

Methods and Experimental Design

Colloidal crystal and MIP fabrication and characterization

Colloidal crystal depositions were achieved by self-assembly of silica nanoparticles from monodispersed SiO2-ethanol suspension of 1.5% (w/v) with the help of the vertical uplifting of a custom-made step-motor. Environmental conditions were optimized for high-quality crystallization. A pre-polymerization solution was prepared by thoroughly mixing 11-kT hormone in ethanol, followed by acrylic acid (functional monomer), EGDMA (crosslinker), and lastly AIBN (initiator). The target to monomer to crosslinker ratio of 1:33:8 was determined through multiple trial and error for acquiring the best MIPs. The solution was allowed to enter the inter particle voids of the colloidal crystal and was polymerized under UV light. The silica particles were then removed using hydrofluoric acid, leaving behind an inverse opal microporous polymer. Finally, 11-kT molecules were washed out using a solution of acetic acid and ethanol (1:9). A non-imprinted polymer (NIP) was also created as a control using the same method, excluding the target molecule. The response of the MIP sensors was evaluated by UV-Visible spectrophotometry, where the peaks shifted to higher wavelength with the binding of target molecule. Both the colloidal crystal and polymer were characterized by SEM imaging. The chemical functional groups and their interactions with the 11-kT molecule after polymerization were investigated by FTIR.

Incubation Study

The MIPs and NIPs were incubated in various analyte solutions with concentrations ranging from 0.1 ppb to 50 ppb in DI water. For investing the effect of ionic strength, the sensors were exposed to solutions in NaCl and CaCl2. To inquire strategies to minimize the non-specific binding effect, NIPs were rinsed with DI water after every incubation in salt solutions, and a final DI water wash was performed after exposing it to the highest target concentration.

Results and Discussion

The sensor showed satisfactory results for detecting 11-kT molecules in water. It can sense the analyte in sub-ppb level as low as 0.1 ppb. The average total diffraction peak shift of the MIPs was 34 nm towards the higher wavelengths, where the NIPs showed an average shift of 7 nm only. The experimental data were fitted to Langmuir and Freundlich equations, where Langmuir isotherm explained the data better for both MIPs (R2= 0.9618) and NIPs (R2= 0.9529), indicating an excellent fit and strong agreement with the model.

In the presence of NaCl, the sensors exhibited a maximum peak shift of 34 nm, comparable to that observed in DI water. This result indicates that monovalent cations have minimal influence on detection performance. However, a slight increase of approximately 3 nm in peak shifts was noted in the NIPs, suggesting a minor rise in non-specific adsorption.

Divalent cations negatively affected the sensing efficiency of the MIPs, causing an average peak shift of 30 nm and substantial non-specific adsorption of 15 nm in the NIPs. Furthermore, the adsorption curve of MIPs in CaCl₂ was lower compared to DI water, indicating an underestimation of the actual analyte concentration. Additionally, both the sensors and the controls experienced wavelength shifts due to salt alone, with greater shifts observed in CaCl₂ than NaCl. The reduced sensing capability in CaCl₂ solutions can be attributed to the bridging effect of Ca²⁺ within the polymer film, which causes the polymer to shrink and make the imprinted sites less accessible by limiting analyte diffusion.[7]

A follow-up experiment was conducted with NIPs to determine whether the shifts caused by non-specific adsorption and salt effects could be minimized. A new set of NIPs was incubated in CaCl₂ target solutions, similar to previous experiments, but with an additional step—rinsing between each incubation and measurement. These DI-rinsed NIPs, along with NIPs previously incubated in NaCl and CaCl₂ solutions without rinsing, were shaken in DI water for 20 minutes to ensure thorough washing. The results showed a partial backshift in NIP-NaCl and NIP-CaCl₂, whereas the DI-rinsed NIP-CaCl₂ exhibited a significant backshift, indicating that non-specific adsorption and the influence of divalent salts were largely reversible.

Conclusion and Future Work

Experiments testing the sensor in the presence of natural organic matter are currently underway, which simulates a natural water environment. Furthermore, the MIPs will be applied for the measurement of 11-kT in fish physiological fluid samples. To date, the developed molecularly imprinted polymeric sensor has demonstrated high efficiency in detecting 11-kT at concentrations as low as 0.1 ppb across a variety of solutions. The sensor is designed to be portable and user-friendly, allowing it to be easily transported to the field for on-site analysis of environmental water samples. This capability will greatly enhance the speed of hormone detection in scientific research. Additionally, the sensor provides a cost-effective and accessible alternative to the traditional HPLC analysis, making hormone detection more efficient. Moreover, it will encourage the monitoring of hormones in drinking and natural waters, ultimately contributing to the reduction of exposure risks for both humans and wildlife.

References:

[1] M. Grzegorzek, K. Wartalska, R. Kowalik, Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2024, 31 (26), 37907–37922. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-33713-z.

[2] M. M. S. Yazdan, R. Kumar, S. W. Leung, Ecologies. 2022, 3 (2), 206–224. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies3020016.

[3] A. Gonsioroski, V. E. Mourikes, J. A. Flaws, Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21 (6), 1929. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21061929.

[4] A. Bohra, Endocrinology & Metabolic Syndrome. 2015, 04. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-1017.1000156.

[5] D. M. Gonçalves, R. F. Oliveira, in Hormones and Reproduction of Vertebrates (Eds: D. O. Norris, K. H. Lopez), Academic Press, London 2011.

[6] J. Rege, A. F. Turcu, J. Z. Kasa-Vubu, A. M. Lerario, G. C. Auchus, R. J. Auchus, J. M. Smith, P. C. White, W. E. Rainey, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018, 103 (12), 4589–4598. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-00736.

[7] R. J. Nap, I. Szleifer, The Journal of Chemical Physics. 2018, 149 (16), 163309. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5029377.