2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(673e) Modelling the Procurement of Vaccines Under Competition:Improved Contracting Approaches to Enhance Supply Chain Resilience Subject to Uncertainty

1 Background

A number of nations have sought to achieve greater vaccine supply chain resilience through increased domestic manufacturing [1], shifting the way in which they procure vaccines. Issues with procurement are noted by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of the most prevalent causes for vaccine stock-outs globally [2]. The interactions between procurement agencies and manufacturers can have a significant impact on public health outcomes [ 3], and so an understanding of the trade-offs made by stakeholders can provide insights into how to achieve mutually beneficial contracting agreements. For many vaccines, differently sized and located manufacturers compete to sell to buyers [4], whilst procurement agencies compete to source sufficient doses from a limited supply [3]. Each of these players holds their own private information, and uncertainty exists surrounding factors including the value of a given vaccine on the international market.

The objective for a procurement agency is how to offer attractive contracts to purchase vaccines from competing manufacturersinawaythatminimizescostandensureslong-termresilience. International manufacturers are generally able to leverage economies of scale to offer lower prices [2], but domestic manufacturing is more resilient in the case of international shortages or disruptions [1]. The procurement agency must balance competing interests in order to maintain the long-term financial health of the domestic manufacturer, while not themselves overspending.

The behaviour of each player can help gauge the merit of different contracting strategies and improve future decision making. We therefore developed a model that can simulate the actions of each relevant player as they aim to meet their own objectives. The model incorporates the uncertainty inherent in decentralised supply chains and defines each player’s perception of the situation, to account for real-world information asymmetry. The novelty of the model is in the simultaneous consideration of competitive procurement (with the option for contract rejection), uncertain market conditions, and continuously changing information asymmetry.

2 Methods

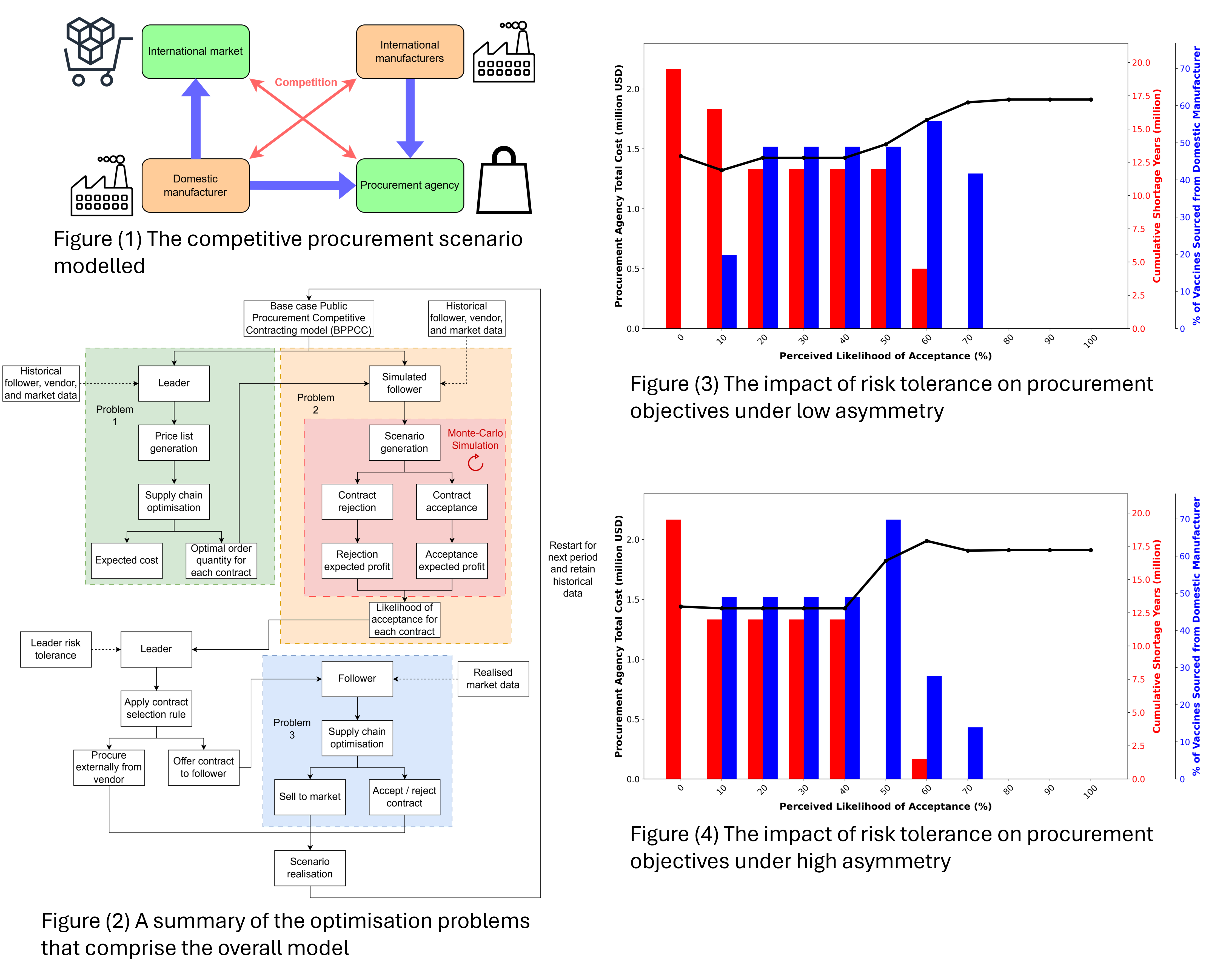

The proposed problem considers the procurement of a privately manufactured vaccine by a public procurement agency. The agency can procure from two competing manufacturers, one of which is domestic and the other international. The agency itself competes with the international market to secure sufficient supply. A summary of the interactions can be seen in Figure 1. The model created is inspired by the works of Hijaila et al. [5].

In the problem explored, the procurement agency considers a number of wholesale contracts, which they hope will be accepted by a domestic manufacturer. The agency selects a single contract to offer based on their perception of the situation, additionally purchasing from an international manufacturer to aim to meet the total demand for the time period. The domestic manufacturer then considers the contract, should they receive one, with knowledge of the now realised (formerly uncertain) situation. They determine if they should accept or reject the contract and decide the number of doses to sell to the international market. The process then restarts for the next time period.

The differing size of each player determines the nature of their relationships, with the larger international manufacturer dictating their pricing structure with the procurement agency (in this case a quantity discounting relationship), whilst the smaller domestic manufacturer can only accept or reject contracts it receives from the agency.

To model the problem, three interlinked optimisation sub-problems are derived to simulate the successive actions of each player. In Problem 1, the procurement agency optimises their supply chain for each possible contract price considered, generating a contract menu. An optimised domestic manufacturer order quantity is produced for a range of wholesale prices considered, along with a corresponding quantity to be purchased from the international manufacturer (which is not disclosed to the domestic manufacturer).

In Problem 2, the procurement agency performs a Monte-Carlo simulation of the domestic manufacturer’s supply chain to account for uncertain parameters. This is repeated for each contract considered. Historical data from the prior period is used for the simulation when up-to-date data is not known by the agency. Simulation scenarios are produced based on a set of values for uncertain parameters, randomly generated from historical distributions. For each of the scenarios, the domestic manufacturer’s expected profit is separately optimized for the cases of contract acceptance and rejection. The proportion of these scenarios that result in an improved profit upon acceptance is perceived as the likelihood of acceptance (LOA) of the domestic manufacturer for that contract, which assists the agency in contract selection.

Following the calculation of the LOA, the agency selects a single contract to offer to the domestic manufacturer based on a pre-defined rule. In this case, the rule is to pick a tolerable LOA (dependent on the agency’s tolerance for risk) and select the contract with the lowest expected cost that surpasses this threshold.

In Problem 3, the domestic manufacturer optimizes their supply chain based on the contract presented to them, a single realised value for previously uncertain parameters, and the information available to them. Contract rejection can result in a supply shortage for the agency. A visual summary of the model described can be seen in Figure 2.

3 Results

The model is applied to a case study surrounding the procurement of the BCG vaccine in Vietnam from 2014 to 2023. The case study is based on contracting data provided by the WHO [6]. BCG is selected as it has experienced severe stockouts in the past, in part as a result of poor procurement [2]. Vietnam has historically procured BCG from domestic and international sources and has relevant data available [6]. The uncertain parameter used is the spot market price that the domestic manufacturer is able to sell for internationally, generated using a multi-modal normal distribution based on relevant contracting data.

The results shown in Figure 3 demonstrate the impact that the risk tolerance of the procurement agency has on their total cost, the degree of collaboration with the domestic manufacturer, and the total supply shortage that occurs as a result of any procurement shortcomings. To ensure results are comparable, a fixed set (but still randomly generated and unknown to the agency) of market price values is used for each LOA explored. It can be seen that greater shortages occur as a result of riskier contracting approaches, but lower costs and greater domestic collaboration can also transpire. At very low LOA levels, the over-opportunistic nature of the contracts offered results in high shortages and no collaboration. No single contracting approach is able to achieve a high degree of collaboration with the domestic manufacturer without suffering a shortage. This creates an outcome where the procurement agency must consider which objective to prioritize. Should small shortages be acceptable, the contracting strategy for a LOA of 60% can offer cost reduction and a comparatively high degree of domestic collaboration. Should shortages not be acceptable, the contracting strategy for a LOA of 70% does allow for a degree of domestic collaboration but at a higher cost. Figure 4 showcases the same scenario but with a higher degree of information asymmetry, with each player making independent predictions about the market price. It can be seen that this asymmetry impacts the actions of the players, with higher total costs for the procurement agency in most cases. Smaller shortages are experienced on some occasions as a result of the additional spending.

4 Implications

The results indicate that, for the scenario presented, there is no contracting approach for which a vaccine procurement agency can achieve a high degree of domestic procurement, minimize costs, and suffer no shortage. This suggests that the agency must be willing to compromise on at least one of their objectives, potentially resulting in long-term detriments to supply chain resilience and therefore public health. From the domestic manufacturer’s perspective, poor coordination can result in erratic domestic contracts that create difficulty with production scheduling and increase the likelihood of wastage. Future work in this area should investigate the tools available to governments to achieve the desired coordination, as wholesale contracting alone cannot accomplish it. These approaches could include manufacturing subsidies, import/export tariffs, and more complex contracting options [7].

References

[1] Rey-Jurado, F. Tapia, N. Muñoz-Durango, M. K. Lay, L. J. Carreño, C. A. Riedel, S. M. Bueno, Y. Genzel, A. M. Kalergis, Assessing the importance of domestic vaccine manufacturing centers: An overview of immunization programs, vaccine manufacture, and distribution, Frontiers in Immunology 9 (1 2018). doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00026.

[2] WHO, Global vaccine market report 2024, Tech. rep., World Health Organisation (WHO) (2024).

[3] Arango-Luque, D. Yucumá, C. E. Castañeda, J. Espin, F. Becerra-Posada, Tiered pricing and alternative mechanisms for equitative access to vaccines in latin america: A narrative review of the literature, Value in Health Regional Issues 42 (2024) 100981. doi:10.1016/j.vhri.2024.01.003.

[4] Behzad, S. H. Jacobson, Asymmetric bertrand-edgeworth-chamberlin competition with linear demand: A pediatric vaccine pricing model, Service Science 8 (2016) 71–84. doi:10.1287/serv.2016.0129.

[5] Hjaila, J. M. Laínez-Aguirre, M. Zamarripa, L. Puigjaner, A. Espuña, Optimal integration of third-parties in a coordinated supply chain management environment, Computers Chemical Engineering 86 (2016) 48–61. doi:10.1016/j.compchemeng.2015.12.002.

[6] WHO, 2024 mi4a public vaccine purchase dataset, World Health Organisation (WHO) (2024).

[7] Chandra, B. Vipin, On the vaccine supply chain coordination under subsidy contract, Vaccine 39 (2021) 4039– 4045. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.081.