2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(187ar) Measurement and Modelling of the Permeability of Polyether Ether Ketone (PEEK) to CO2 at High Pressures

An application of polymers for the energy transition is in the capture, transport and storage of CO2; this has a relatively high solubility in many polymers and is corrosive to mild steel [1], which is a preferred choice, owing to its low cost. Polyether ether ketone (PEEK) has attracted significant interest as a corrosion protection liner, because it has a relatively low permeability to fluids, resistance to a broad range of chemicals, and can operate at high temperature (up to e.g. 250 °C). This work investigates the permeation of CO2 through semicrystalline PEEK (supplied directly by its manufacturers, Victrex) at conditions relevant to the transport and storage of CO2: up to a pressure of 400 bar, and below the glass transition temperature of ~ 140 °C determined for the pure polymer i.e. the amorphous fraction of the polymer is in its glassy state, in the absence of CO2.

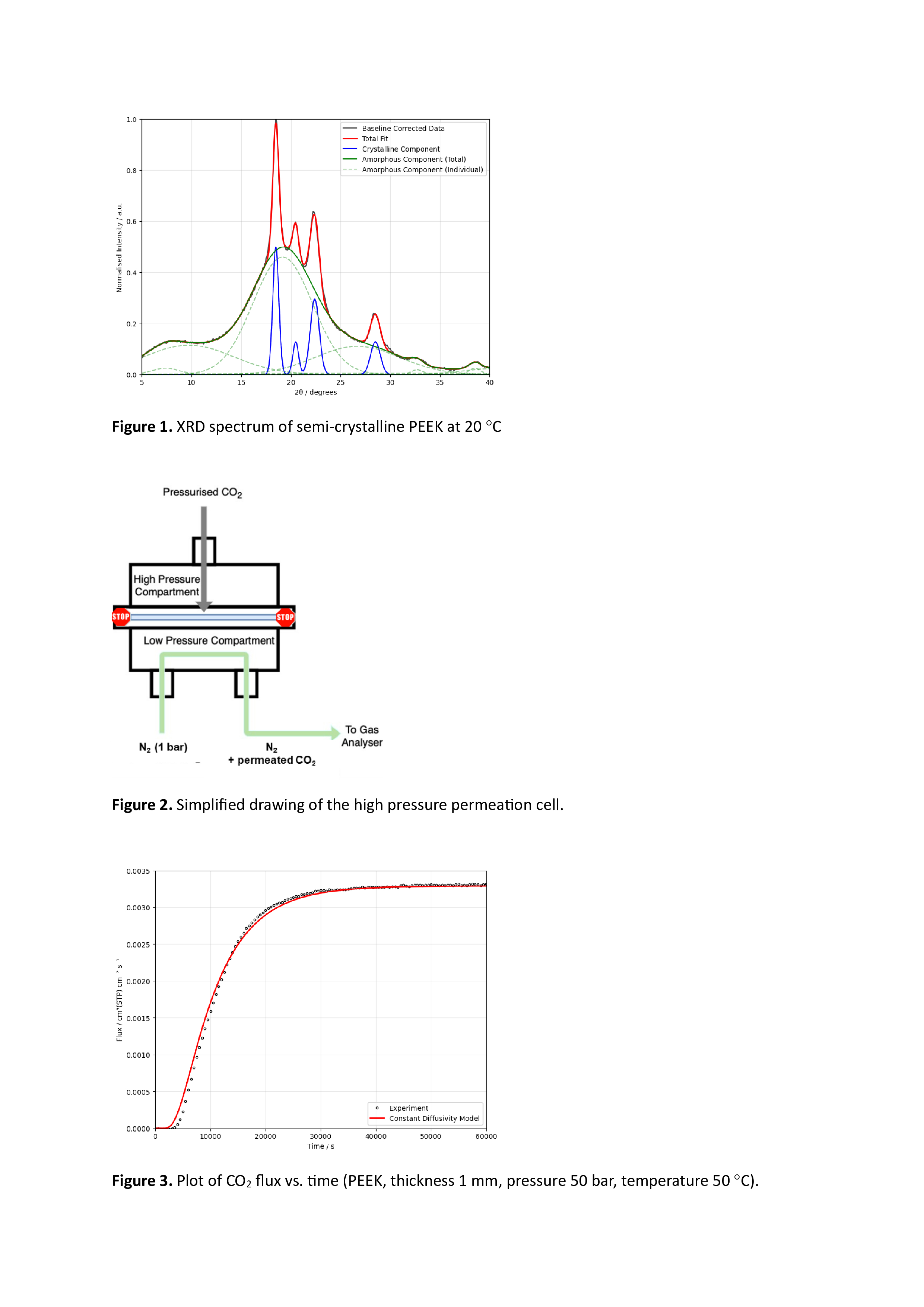

The permeability of a polymer to a fluid is a combination of two factors: (1) the solubility of the fluid in the polymer, which can (in theory) be predicted by a thermodynamic equation of state and (2) the diffusivity of the molecules in the polymer matrix, which is a kinetic property. Although the crystallites in a semicrystalline polymer are typically assumed to be impermeable, the degree of crystallinity affects both (1) and (2) in a somewhat complex way. Consequently, the fractions of crystalline and amorphous PEEK were comprehensively characterised using both differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and X-ray diffraction (XRD). Figure 1 shows an XRD spectrum of the PEEK at ambient temperature; a Gaussian peak-fitting algorithm was developed, in order to differentiate the contributions of the amorphous and crystalline polymer to the spectra, and to determine the proportions of each.

Next, the permeability of the PEEK to CO2 was measured at up to 400 bar and elevated temperature, using a high-pressure permeation cell developed at Imperial College London [2]. Figure 2 is a simplified drawing of the cell; the polymer sample, supported by a sintered metal disc, was sandwiched between two plugs. The upper compartment was pressurised with CO2, whilst the lower compartment was swept with nitrogen to a sensitive analyser, which quantified the concentration of CO2 (of the order of tens of parts per million). Several hours after pressurisation, CO2 was detected in the analyser, eventually rising to a steady state; this is exemplified by the transient breakthrough curve shown in Fig. 3. From these curves, indirect estimates of solubility and diffusivity can be elucidated by fitting parameters to an appropriate transport model. However, a simple transport model assuming constant diffusivity was found to deviate from the experimental measurement; the best-fitting breakthrough curve predicted by this model is superimposed on the experimental breakthrough curve in Fig. 3.

In fact, we noted a similar deviation from the constant diffusivity assumption in previous work [2] on the permeation of CO2 through semicrystalline polymers HDPE and PTFE, above their glass transition temperatures (i.e. with their amorphous domains in the rubbery state). A transport model, based on free volume theory, was developed to account for the increase in polymer free volume, owing to the presence of CO2. Modelling the transport of CO2 through a polymer such as PEEK, in its glassy state, is even more difficult, because it can be plasticised by the CO2; this induces a transition of the amorphous domain to the rubbery state, even below the glass transition temperature of the pure polymer. This transition can cause a sharp change in diffusivity, which was not well-represented by our earlier model, in which the free volume of the polymer smoothly and linearly increased with the volume fraction of CO2. Thus we compare the predictions of a new model, which better represents the CO2-induced transition from the glassy to the rubbery state, to measured transient breakthrough curves.

The combination of permeation measurement and transport modelling developed in this work contributes to the design and selection of polymeric materials for engineering applications, in particular those involving solute-polymer systems at high pressure.

References

[1] R. Jasinski, Corrosion of N80-Type Steel by CO2/Water Mixtures, Corrosion 43 (1987) 214–218.

[2] T. Hu, Permeation of High Pressure CO2 in Semicrystalline Polymers. PhD Thesis, Imperial College Longon (2021).