2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(450g) Kinetic Investigation of CaCl2 Assisted Carbothermic Fe Reduction in Vanadium Bearing Titano-Magnetite Ore.

Titano-magnetite ores are globally distributed and gaining interest in the clean energy transition as they contain valuable metals including iron (Fe), titanium (Ti), and often vanadium (V). Ti, valued for its strength to weight ratio and corrosion resistance, is widely used in aerospace and wind turbines (Wang et al., 2023). V, a vital steel additive, also serves as a key component in REDOX flow batteries due to its multiple oxidation states and high energy capacity (Moskalyk & Alfantazi, 2003). Despite their potential as a single ore source for Ti and V, titano-magnetite ores are often overlooked due to their lower grades of Ti and V compared to ilmenite and blast furnace steel slag. Moreover, blast furnaces used for iron making, as well as extraction of Ti and V from ilmenite and blast furnace steel slag requires smelting minerals at temperatures exceeding 1500 °C and are energy-intensive processes (Zietsman & Pistorius, 2006; Cheng et al., 2025).

Alternatively, the CaCl2 assisted reduction process preferentially metallizes Fe below 1200 °C enabling low-intensity magnetic separation of an alloy phase for steelmaking from a Ti and V-enriched residual fraction. CaCl₂ acts as a flux, promoting the diffusion of iron species to solid carbon reductants, where carbothermic reduction produces iron and iron carbides. During this reduction process, oxygen from iron oxides reacts with carbon to generate CO and CO2. CaCl₂, as a flux material, offers advantages such as reusability and potentially improved reaction kinetics for Fe reduction in titano-magnetite based on previous research by Paktunc et al., (2024). Li et al., (2020) also found that CaCl2 promoted Fe metallization during carbothermic reduction of titano-magnetite ore, however Li et al embedded ore and CaCl2 pellets inside bituminous coal and used a lesser proportion of CaCl2 relative to ore, and a higher dwell temperature (1300 °C) than the present study. The overall reduction reactions (Equations 1 – 3) and transformation of Fe to Fe3C (Equation 4) are presented. CO also facilitates the reduction of magnetite (Equation 5) (Shi et al., 2018).

Fe3O4 + 4C = 3Fe + 4CO Eq. 1

Fe(Fe,Ti)O4 + 2C = 2Fe + TiO2 + 2CO Eq. 2

FeTiO3 + C = Fe + TiO2 + CO Eq. 3

3Fe + C = Fe3C Eq. 4

Fe3O4 + 4CO = 3Fe + 4CO2 Eq. 5

This study therefore examines the effects of temperature and CaCl₂ proportion on Fe metallization, kinetics, and the reduction mechanism to enhance our understanding of CaCl₂-assisted carbothermic reduction of Fe from titano-magnetite ores and evaluate its feasibility.

Methodology

Titano-magnetite ore from the Magpie mines deposit (QC, Canada) was milled and sieved to a particle size of -180 + 38 µm. Its composition determined using ICP-OES is shown in Table 1. XRD analysis identified titano-magnetite Fe(Fe,Ti,V)2O4 as the primary phase, with gangue minerals including ilmenite FeTiO3 and plagioclase Na1−xCaxAl1+xSi3−xO8 (where x = 0 – 1).

The ore was then mixed and pelletized with calcined petcoke as a reductant (95.8 wt% C by ultimate analysis, particle size -106 + 75 µm. Asbury, NJ, USA) and anhydrous CaCl2 as flux. The ore to petcoke mass ratio was set at 100 : 18, ensuring C in excess relative to O bound to Fe-oxides in the ore. The flux proportion was varied as indicated, and 6 wt% water was added as a binder to facilitate pelletization.

Pellets were then reduced in a simultaneous thermal analyzer (Netzch Jupiter 449A, Germany) using Gr 5.0 Argon to maintain an inert atmosphere.

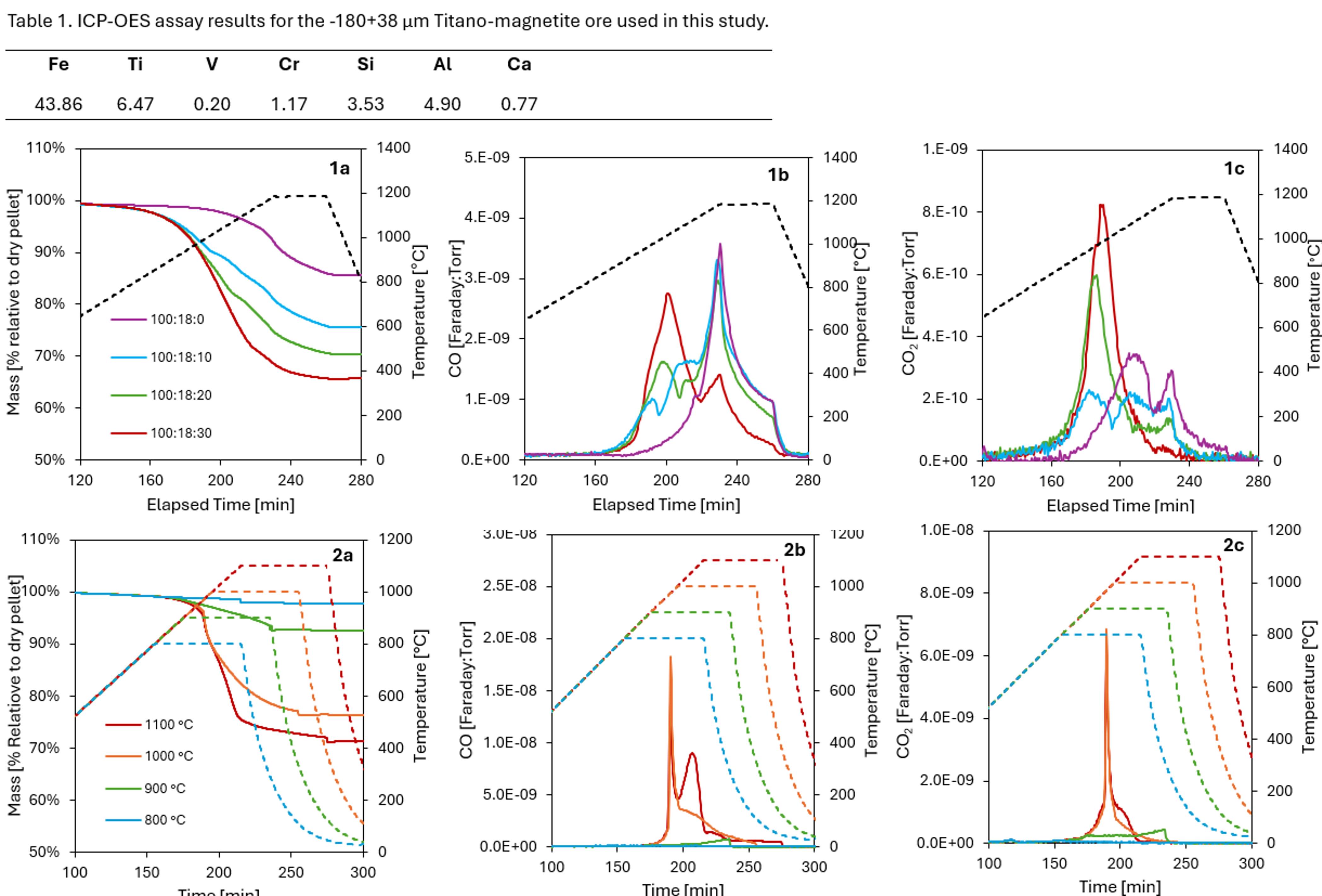

Table 1. ICP-OES assay results for the -180+38 µm Titano-magnetite ore used in this study.

Results

Thermally ramped experiments were conducted to examine the effects of CaCl2 proportion on CO and CO2 off-gas profiles and mass loss. Ore : reductant : flux mass ratios of 100: 18 : {0 , 10, 20, 30} were tested. Samples were heated at a rate of 5 °C·min-1 to a dwell temperature of 1200 °C, which was maintained for 1 hour. Initial pellet masses ranged from 42 to 46 mg, with mass loss and off-gas profiles shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mass loss and off-gas profiles for thermally ramped experiments with specified ore : CaCl2 proportions. Ar was used at a flow rate of 100 ml·min-1 during heating and then the 1200 °C dwell period, increasing to 480 ml·min-1 during cooling. (1a) Mass loss curves; (1b) CO off-gas profiles; (1c) CO2 off-gas profiles.

Figure 1a demonstrates that relative mass loss increases with the proportion of CaCl₂ flux, with a maximum at 34% of the dry pellet mass for a 100:30 ore-to-CaCl₂ ratio. Figure 1b reveals that CaCl₂ addition induces CO evolution shortly after its melting at 772 °C, which is absent in the control experiment without CaCl₂. Figure 1b also shows up to three CO-generating events occur during magnetite reduction below 1200 °C, with the magnitude of the first event correlated to the flux proportion. Figure 1c shows corresponding CO₂ evolution with three distinct events, where the rate of the first event exceeds that of CO evolution. The magnitude of CO₂ events is smaller compared to CO.

Isothermal experiments were performed to investigate the effect of reduction temperature on CO and CO2 off-gas profiles and mass loss. Samples with an ore : reductant : flux ratio of 100: 18 : 30 were heated at 5 °C·min-1 to dwell temperatures of 800 °C - 1100 °C, maintained for 1 hour. Initial pellet masses ranged from 225 to 240 mg. Mass loss and off-gas profiles are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Mass loss and off-gas profiles for isothermal experiments with a 100 : 30 ore : CaCl2 proportion. Ar was used at a flow rate of 100 ml·min-1 during heating and the maximum temperature dwell period, increasing to 480 ml·min-1 during cooling. (2a) Mass loss curves; (2b) CO off-gas profiles; (2c) CO2 off-gas profiles.

Figure 2a indicates less than 7% mass loss at dwell temperatures ≤900 °C, while mass loss accelerates significantly during the early stages of reduction up to dwell temperatures of 1000 °C and 1100 °C. Figure 2b demonstrates minimal CO evolution below 900 °C but identifies two CO-generating events at dwell temperatures of 1000 °C and 1100 °C. Notably, the second event is more pronounced at 1100 °C. Figure 2c shows lower CO₂ evolution than CO in Figure 2b, with comparable CO₂ evolution at 1000 °C and 1100 °C, returning to baseline levels before the end of both dwell periods.

Discussion and conclusions

Mass loss results (Figures 1a and 2a) alone cannot fully characterize titano-magnetite ore reduction, as they fail to distinguish between oxygen removal (as CO or CO₂) and chloride volatilization (e.g., FeCl₃, FeCl₂, and CaCl₂). This underscores the need to analyze off-gas profiles and characterized products to comprehensively understand reduction mechanisms and Fe metallization in this process. This preliminary work prioritizes off-gas profile evaluation, with product characterization to be addressed in future studies by the authors.

CO and CO₂ profiles (Figures 1b-c) confirm that using up to 30 parts CaCl₂ flux relative to ore achieves enhanced reduction kinetics and reduces processing time. Additional tests are required to confirm whether greater flux proportions could further accelerate reduction. Figures 2b-c indicate that a minimum dwell temperature of 1000 °C and a duration of 1 hour are necessary for effective Fe reduction, which is supported by the observation of CO₂ profiles reaching baseline and CO profiles stabilized at a sufficiently low level in this time. For comparison, the pellets reduced by Li et al., (2020) were held at 1300 °C for 150 minutes. Additionally, the retention time for iron ore in blast furnaces can be more than 5 hours, and the metal and slag temperatures 1350 – 1450 °C and 1500 – 1550 °C respectively (Bailera et al., 2021). Longer dwell times in the CaCl2 assisted reduction process may increase Fe-alloy recovery, with diminishing energy efficiency due to slwer kinetics as metallization nears completion.

By inspection, the integrated areas of CO and CO₂ off-gas profiles correlate with oxygen removal via carbothermic reduction by solid carbon and secondary reduction by CO as described by equations 1 - 5. CO evolution arising from solid C acting as the reductant is dominant, while CO₂ evolution confirms complementary reduction by CO. Analysis of post-reduction products is needed to assign specific reduction events to Fe phases (e.g., ilmenite vs. magnetite) and track Fe transitions from its 3+ and 2+ to zerovalent state, which will be discussed during the presentation.

In conclusion, CaCl₂-assisted carbothermic reduction is a promising alternative technology for reducing Fe in titano-magnetite ore at lower temperatures compared to blast furnaces, and shows potential for further optimization. Future research should prioritize detailed phase characterization and flux interactions to further enhance process efficiency, recovery yields, and investigate the potential for V-Ti enrichment in the residual fraction.

References

Bailera, M., Nakagaki, T., & Kataoka, R. (2021). Revisiting the Rist diagram for predicting operating conditions in blast furnaces with multiple injections. Open Research Europe, 1(141). https://doi.org/10.12688/openreseurope.14275.1

Cheng, S., Li, W., Vaughan, J., Ma, X., Chan, J., Wu, X., Han, Y., & Peng, H. (2025). Advances in the integrated recovery of valuable components from titanium-bearing blast furnace slag: A review. Sustainable Materials and Technologies, 35, e01384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2025.e01384

Li, X.H., Kou, J., Sun, T.C., Wu, S.C., & Zhao, Y.Q. (2020). Effects of calcium compounds on the carbothermic reduction of vanadium titanomagnetite concentrate. International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy and Materials, 27(3), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12613-019-1864-z

Moskalyk, R. R., & Alfantazi, A. M. (2003). Processing of vanadium: A review. Minerals Engineering, 16(9), 793-805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0892-6875(03)00213-9

Paktunc, D., Coumans, J. P., Carter, D., Zagrtdenov, N., & Duguay, D. (2024). Mechanism of the direct reduction of chromite process as a clean ferrochrome technology. ACS Engineering Au, 4(1), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsengineeringau.3c00057

Shi, L.Y., Zhen, Y.L., Chen, D.S., Wang, L.N., & Qi, T. (2018). Carbothermic reduction of vanadium-titanium magnetite in molten NaOH. ISIJ International, 58(4), 627–632. https://doi.org/10.2355/isijinternational.ISIJINT-2017-515

Wang, Z., Tan, Y., & Li, N. (2023). Powder metallurgy of titanium alloys: A brief review. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 953, 171030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.171030

Zietsman, J. H., & Pistorius, P. C. (2006). Modelling of an ilmenite-smelting DC arc furnace process. Minerals Engineering, 19(3), 262–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2005.06.016