2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(390i) Integrating Hydrothermal Liquefaction and Anaerobic Digestion for Enhanced Carbon Recovery from Municipal Solid Waste

Authors

Thermochemical conversion technologies, including gasification, pyrolysis, and hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL), are attractive as they can handle a variety of mixed feedstocks, and they are preferable to incineration as they convert the waste into secondary energy carriers (liquid or gaseous fuels) or chemicals. Gasification involves high-temperature conversion of organic material into syngas, which can be used for power generation or further upgraded into chemicals or fuels. Pyrolysis, which is conducted at more moderate temperatures in the absence of oxygen, produces bio-oil, char, and syngas but often requires extensive upgrading of the bio-oil due to its high oxygen content. HTL converts wet biomass into biocrude oil in subcritical water (250–374 °C, 4–22 MPa) and it is advantageous over pyrolysis and gasification because it can directly utilise wet biomass (food waste, sewage sludge, etc.). In addition, HTL oils have higher calorific values and lower oxygen content compared to pyrolysis oils, and therefore reduced upgrading costs [4,5].

However, a major bottleneck of the HTL process, limiting its economic and technical scalability, is the production of an aqueous phase by-product (HTL-AP) that can contain up to 50% of initial carbon in the feedstock. The HTL-AP has too high an organic load to be disposed without treatment, while its valorisation is important to increase the carbon efficiency and economic performance of the process. Moreover, HTL-AP treatment could improve the net energy recovery from HTL by offsetting the energy needed to heat up the reactor and upgrade the oil [6].

Watson et al (2020) [5] compared different methods for the valorisation of HTL-AP, including recycle to the HTL reactor, separation of chemicals using membranes, utilisation as feedstock for microalgae cultivation or anaerobic digestion, bioelectrochemical conversion to H2, and hydrothermal gasification. Recycling of the HTL- AP to the HTL reactor has two key advantages: it reduces the need for fresh water as reaction solvent and increase the overall HTL-oil yield. However, as the recycle ratio increases, the organic content of the HTL-AP also increases, and the final effluent still requires treatment. Thermochemical and bioelectrochemical conversion can produce H2 to be used for HTL-oil upgrading but are hindered by high costs. Anaerobic digestion (AD) is preferred to algae cultivation for conversion of HTL-AP due to its higher tolerance to contaminants present in the HTL-AP and its lower cost [7]. Moreover, AD is already a widely implemented biological process for the treatment of biodegradable waste in MSW and wastewater treatment plants.

In this work, the integration of an HTL unit in the Biffa Wanlip site in Leicestershire (UK) is investigated. Currently at the Biffa site, household waste collected from the Leicester area is sorted to recover its organic fraction. This organic fraction is made into a slurry by combining it with water and passed through a screw press to remove fibrous material that cannot be degraded by the anaerobic micro-organisms. The aqueous stream recovered from the screw press is sterilised by heating it up to 71 °C, after which it is fed to the on-site anaerobic digesters. The digester feed only contains about 30% of the original carbon content while the rest remains in the non-digestible fraction and is currently disposed to landfill.

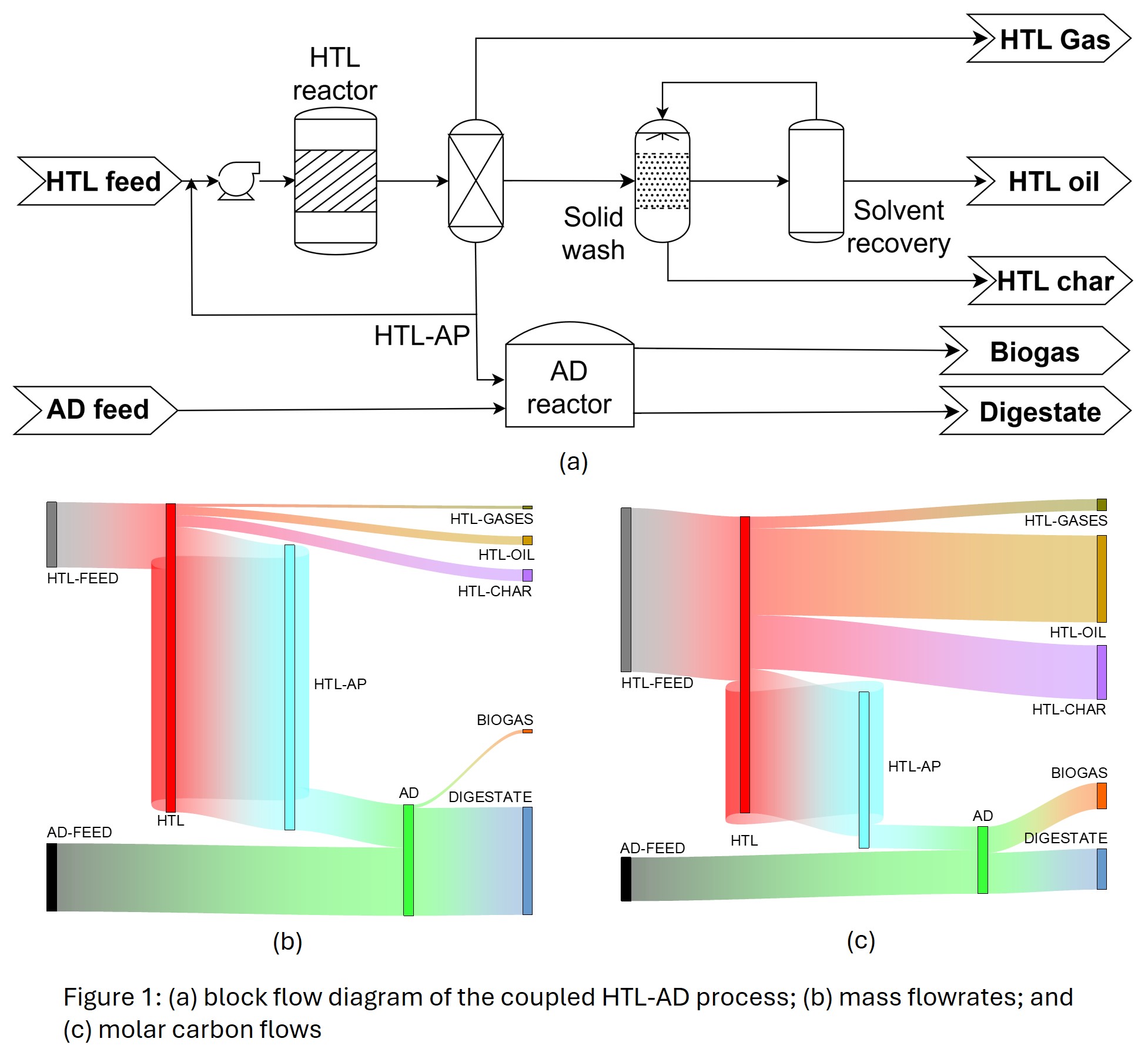

The integration of HTL with AD (Figure 1(a)) presents several key advantages. Firstly, it enables the utilization of both easily degradable organic matter (via AD) and more recalcitrant fractions (via HTL), ensuring a better valorisation of MSW. Secondly, the aqueous phase generated from HTL, rich in soluble organics and nutrients, can be recycled into the AD process, potentially enhancing microbial activity and biogas production and reducing freshwater demand.

The coupled HTL-AD process (Figure 1(a)) was simulated in Aspen Plus v12.1. The HTL-feed is co-fed with some recycled HTL-AP to the HTL reactor. The recycling rate of HTL-AP is set to keep a 1 in the stream entering the HTL reactor. A 3-phase separator separates the gases from the oily char and the aqueous phase. The HTL-oil product is obtained by washing the oily char with an organic solvent. Part of the HTL-AP is mixed with the AD-feed and sent to the digester where biogas is obtained as main product.

Both the mass and carbon flows in the coupled HTL-AD process are represented as Sankey diagrams in Figure 1(b) and 1(c), respectively. It can be seen that the HTL-AP and digestate streams are the largest as they contain most of the water. However, the carbon flows highlight how the HTL process successfully recovers about 40% of the carbon contained in the HTL-feed that would otherwise be lost to landfill. Although the HTL-char may contain heavy metals and other contaminants that it is a more stable form of carbon, less prone to decomposition and greenhouse gas emissions than the original HTL-feed. Finally, the use of heat integration can reduce the external utilities consumption by approximately 80%. The overall energy efficiency of the system on a LHV basis is around 50% when considering only the oil and biogas as valuable products, increasing to 80% if HTL-char were also used for energy recovery.

Future work will look into opportunities for recirculating some of the digestate to the HTL reactor to further increase oil-yield and carbon recovery.

References

[1] Bachmann, M., et al. (2023) “Towards circular plastics within planetary boundaries.” Nature Sustainability5: 599-610.

[2] Kaza, S., et al. (2018) “What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050”. Urban Development. World Bank.

[3] Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-waste-data/uk-statistics-on-waste Last accessed: 04/04/2025

[4] Hongthong, S., et al. (2018) “Co-processing of common plastics with pistachio hulls via hydrothermal liquefaction”. Waste Management .102, 351–361.

[5] Watson, Jamison, et al. (2020) “Valorization of hydrothermal liquefaction aqueous phase: pathways towards commercial viability.” Progress in Energy and Combustion Science77:100819.

[6] Liu, Tianqi, et al. (2022) "Recent advances, current issues and future prospects of bioenergy production: a review." Science of the Total Environment810: 152181.

[7] Si, B., et al., (2019) “Anaerobic conversion of the hydrothermal liquefaction aqueous phase: Fate of organics and intensification with granule activated carbon/ozone pretreatment.” Green Chem. 21, 1305–1318.