2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(95a) An Integrated Approach for Process Development and Assessment in the Framework of Bioprocesses for Sustainable Energy Transition

Bioprocesses are expected to partially replace fossil fuels-based ones to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and valorise unconventional sources such as biomass and in general wastes. This implies a radical shift in process development and process system engineering. Indeed, bioprocesses present higher complexities compared to conventional industrial ones owing to several factors:

- Feedstock complexity and variability (seasonal and regional) in composition and availability.

- The more complex structure leads to more complex processes. This results in a significant number of steps to turn the feed into final products. Final products are often a mixture of several components, and their separation may be energy-intensive, especially when diluted in aqueous solutions. Hence, the higher number of process operations and the corresponding demanding purification could be detrimental to the economics and overall profitability. Thus, it could limit the deployment and assessment of the environmental benefits.

- The significant variability of the feedstock and its intrinsic complexity also results in an exponential plethora of possible products and intricated chemistry.

- Novel technologies and process layouts are designed to improve yield and carbon efficiency. These new options are often unconventional unit operations. New tools are expected to improve the design and better qualify these new technologies.

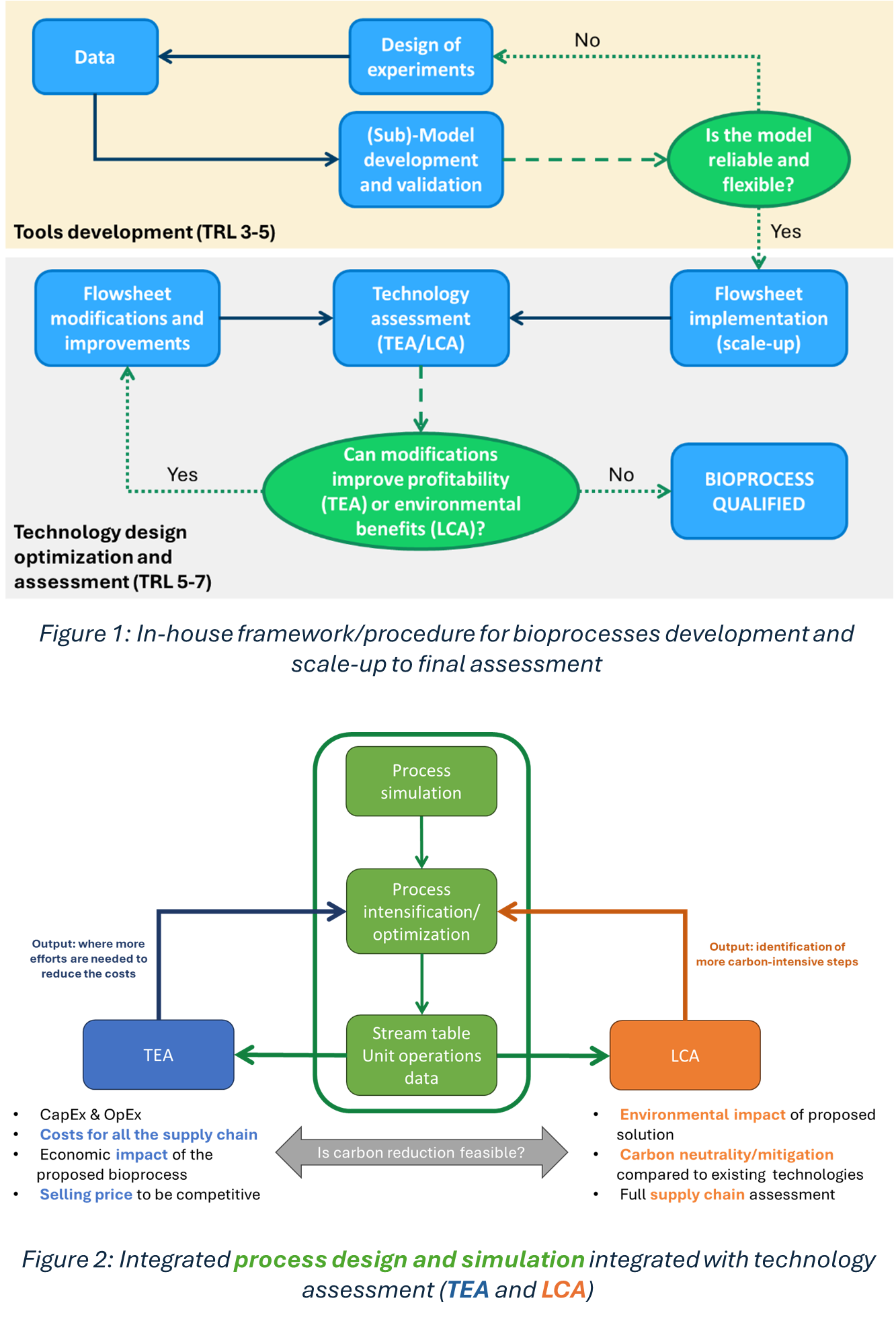

Process modelling and design are challenging for the listed reasons. In addition, process simulation requires reliable models and tools that should be developed taking advantage of experimental data. If the models are not reliable or there are uncertainties associated with their possible application beyond the validation domain, extra measurements are required, possibly through the design of experiments; DoE (Figure 1). Only robust models can be considered for scale-up, optimization, and technology assessment purposes.

Generally, the large variability of biomass and the wide range of operating conditions do not allow extensive experimental campaigns for model development and validation. Hence, selecting the right model based on the available data is crucial. We identified three different classes of modelling:

- Rigorous models follow a rigorous theoretical approach. This approach is general and considers all possible events occurring within the system through detailed kinetic schemes, whenever needed, mass and heat transfer, momentum balance as well as any transport phenomena relevant to characterize the system. The development of rigorous models is time-consuming and requires large datasets for validation.

- Data-driven models rely on observations rather than on physically rigorous relationships developed for the assigned system. These are often yield or conversion-based models, where the yield (or any relevant key performance indicator) of a process is defined as a function of key operating conditions using adjustable parameters. These are often tuned upon measurements from dedicated experimental campaigns covering the operating conditions domain of interest. Needless to mention, such models are simple, flexible, and easy to use. The extension beyond the validation domain is not granted; for this reason, the DoE should be properly planned.

- Shortcut models are at the highest level of simplification and are designed to get preliminary mass and energy balance, using basic thermodynamics and assumptions rather than for detailed engineering purposes. This simplified approach accounts for fixed parameters, e.g., generally conversion or product yield, derived from experience, existing facilities, and literature. Complex units are modelled as a black box, whenever there is neither the need to provide details on the process nor enough data available to generate comprehensive/detailed models. Short-cut models aim to address preliminary estimates of the process without any need for testing the sensitivity to the operating condition and inputs.

Beyond the hurdles and challenges in the model development, demonstrating the environmental benefits without compromising the economics is the key challenge for bioprocesses. For this reason, though process engineering should deliver robust models for process development and simulation; this should be integrated with technology assessment, mainly techno-economic (TEA) and life cycle (LCA) assessments (Figure 2). The strict control of the different steps of the technology development from the model development and linking/merging technology simulation/design with assessments within a recursive procedure are winning strategies. Indeed, the proposed iterative procedure allows for speeding up the scale-up while identifying the weaknesses of the proposed solution. For instance, the process flowsheet, i.e., stream table and unit operations data are used for the TEA and LCA. The TEA can identify the most significant item of cost and which units/sections need significant improvements through either intensification or optimization. Moreover, TEA itself provides useful insight into the current market price and can suggest what kind of support national and international legislation is supposed to implement to support and facilitate the deployment of bioprocesses. Changes in the process layout can be considered at this stage also to evaluate other options. In parallel, LCA can identify the most carbon-intensive steps and support the process design by suggesting less carbon-intensive alternatives for consumables and the supply chain of the raw materials. Remarkably, the carbon mitigation/reduction should be always subjected to process profitability in the proposed iterative process.

The presentation will show successful case studies from our recent EU and nationally-funded projects on biowastes valorisation for biofuels/chemical production.

Acknowledgement

The present work received co-funding from the Research Council of Norway program through the Bio4Fuels project (Grant Agreement N. 257622) and European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme under FUEL-UP (Grant Agreement N° 101136123), HYIELD (Grant Agreement N° 101137792), REFOLUTION (Grant Agreement N°101096780), VALUABLE (Grant Agreement N°101059786), and SEMPRE-BIO (Grant Agreement N°101084297).