2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(423b) An Innovative Integrated Biorefinery Concept with Carbon-Negative Emissions: Combined Techno-Economic (TEA) and Environmental Impact (LCA) Assessments

Authors

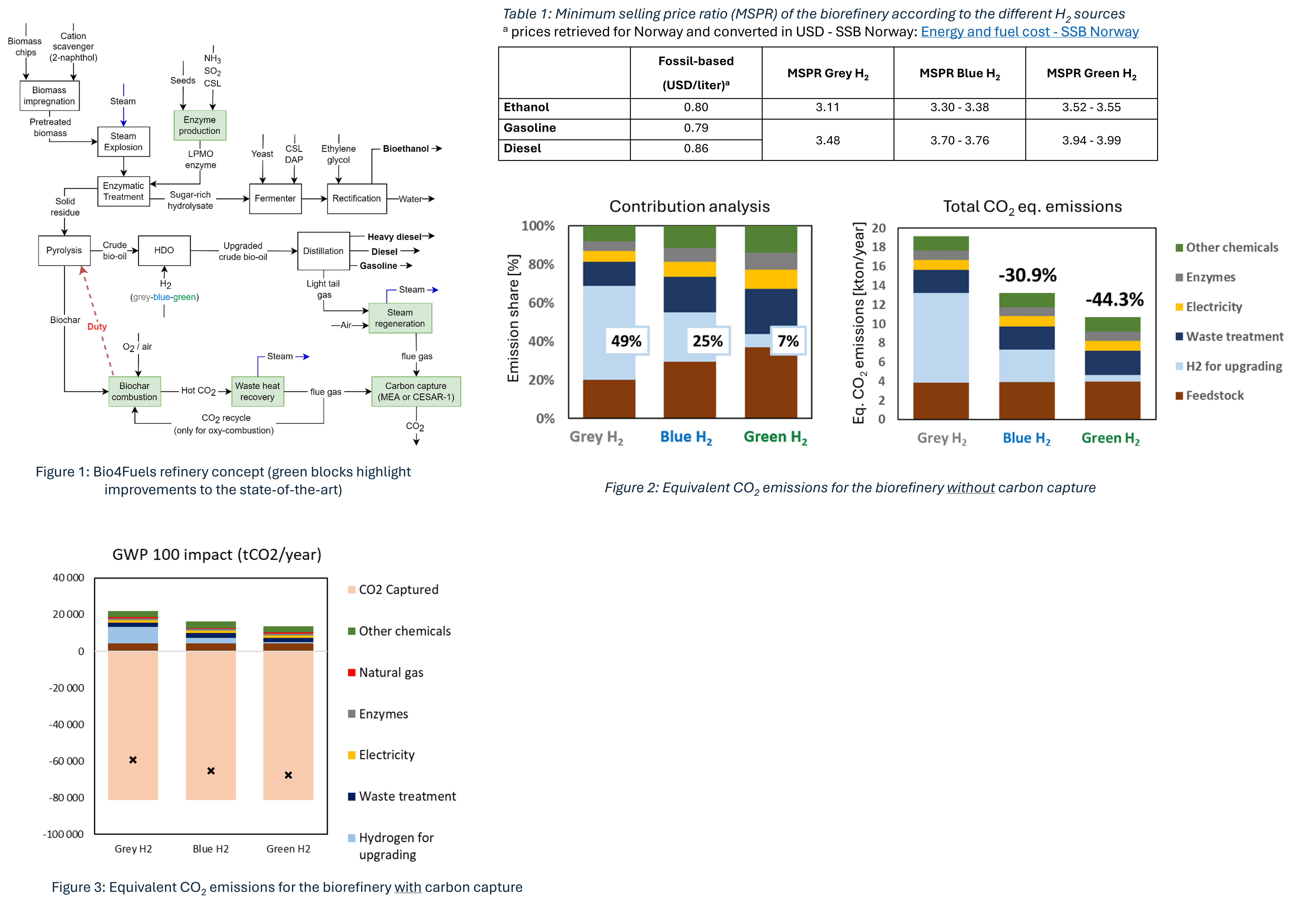

The biorefinery treats 100,000 tons/year of Norwegian spruce chips and is located in Norway. The process has been modelled, designed, and scaled up starting from lab-scale step-up and measurements collected within the Bio4Fuels project [1]. Biomass pretreatments, namely, cation scavenger and steam explosion, are the success key to increasing the biorefinery yield [2]. The biorefinery is designed to split and valorise the different biomass constituents according to different routes: cellulose and hemicellulose undergo fermentation to turn C6 and C5 sugars into bioethanol, which is purified later to fuel grade, while lignin to pyrolyzed to produce char and bio-oil [3]. The valorisation of internal waste/side products is another key step to improve profitability [4] [5]. Indeed, in the new configuration, biochar is burnt to generate the heat for pyrolysis and steam for biomass pretreatment, i.e., steam explosion, and bioethanol azeotropic distillation. Our analysis considered also the economics and environmental impacts of different hydrogen sources for the stabilization of the crude pyrolysis bio-oil via hydro-deoxygenation (HDO). Before any assessment, the process has been optimized in terms of energy integration and maximization of internal resources to minimize the demand for external consumables and raw materials such as on-site enzyme production and the possibility of recovering cation scavengers from bio-oil, e.g., phenols, for biomass pretreatment to improve the separation between cellulose and hemicellulose from lignin.

Beyond process design and optimization already proposed in other works [4] [5], the techno-economic analysis (TEA) and environmental analysis, part of the life cycle assessment (LCA), pointed out:

- The cost of biofuels (bioethanol and fractionated stabilized biofuels) is still not competitive with conventional fossil fuels. The resulting minimum selling price (MSP) for bioethanol and biofuel (with specs compatible with blending with fossil fuels) is estimated three times or even higher than fossil fuels with some distinctions according to hydrogen source. Table 1 provides the costs of biofuels as minimum selling ratio (MSPR), i.e., the ratio between the estimated price to have a profitable biorefinery with a minimum IRR = 10% and the current selling price of the same product from the conventional fossil fuel-based production process.

- Burning biochar (carbon-negative “fuel”) and light gas (i.e., mainly poor-quality syngas) from pyrolysis avoids consuming natural gas. This is a way to valorise side-products and minimize waste and dependence on external utilities/consumables.

- The economic analysis for the proposed process identified the items that should be optimized to drop capital investments (CAPEX) and operational costs (OPEX):

- Pretreatments (impregnation, steam explosion, and enzymatic saccharification) are 15% of the CAPEX. Biomass pretreatment is compulsory, and the technology should account for improvements to reduce the cost.

- Feedstock (wood chips), hydrogen, and cation scavengers are the most significant items of costs for OPEX. Hydrogen weights for 13% (grey), 26% (blue), and 42% (green) of the total annual OPEX. Hydrogen cost is related to technology development and how the research will reduce and introduce improvements to the status; whereas, cation scavengers include a wide range of compounds, for instance, phenols what could be recovered within the stabilized bio-oil fractionation. The problem in the supply chain was analysed in another work and how this could be mitigated [6].

- The H2 cost should drop regardless of the colour. The optimal price is estimated at around 1.5 USD/kgH2. Green H2 has a positive environmental impact, i.e., effective reduction of equivalent greenhouse gas emissions, but its price should go rapidly below 2.8-3.1 USD/kgH2 otherwise the economic profitability of the process is compromised without long-term incentives for bioethanol and biofuels.

- The biorefinery without carbon capture is still carbon-positive, however, the hydrogen colour has a significant role in reducing the equivalent CO2 emissions of the system (Figure 2). Green H2 from offshore wind energy in Norway can cut 44.3% of the total emissions compared to the same process fed with grey H2.

- Capturing CO2 from the fuel gas leads to a carbon-negative process regardless of the hydrogen source (Figure 3). Carbon capture optimization with MEA and CESAR-1 solvents and its corresponding economics are reported in [7]. Remarkably, carbon credits could represent an additional income for the biorefinery. The carbon negativity is achieved by coupling waste combustion with carbon capture. In other words, the biorefinery can achieve carbon-negative conditions even when wastes are burnt but the resulting CO2 is captured.

- The cost of capturing CO2 from a small-middle scale biorefinery, i.e., 100 kt/year, is around 240 USD/tCO2. Cost is rather high due to the economy of scale, but the possibility of sharing the carbon capture facility, i.e., exploiting the economy of scale in an industrial cluster will reduce both investment and operational expenditures as already shown in the literature [8] [9].

Acknowledgement

The present work received financial support from the Research Council of Norway program through the Bio4Fuels project (Grant Agreement N. 257622).

References

[1] L.D. Hansen, M. Østensen, B. Arstad, R. Tschentscher, V.G.H. Eijsink, S.J. Horn, A. Várnai, 2-Naphthol Impregnation Prior to Steam Explosion Promotes LPMO-Assisted Enzymatic Saccharification of Spruce and Yields High-Purity Lignin, ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 10 (2022) 5233–5242. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c00286.

[2] M. Gilardi, F. Bisotti, O.T. Berglihn, R. Tschentscher, V.G.H. Eijsink, A. Várnai, B. Wittgens, Soft modelling of spruce conversion into bio-oil through pyrolysis – Note I: steam explosion and LPMO-activated enzymatic saccharification, in: A.C. Kokossis, M.C. Georgiadis, E. Pistikopoulos (Eds.), Computer Aided Chemical Engineering, Elsevier, 2023: pp. 757–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-15274-0.50121-9.

[3] F. Bisotti, M. Gilardi, O.T. Berglihn, R. Tschentscher, V.G.H. Eijsink, A. Várnai, B. Wittgens, Soft modelling of spruce conversion into bio-oil through pyrolysis – Note II: pyrolysis, in: A.C. Kokossis, M.C. Georgiadis, E. Pistikopoulos (Eds.), Computer Aided Chemical Engineering, Elsevier, 2023: pp. 769–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-15274-0.50123-2.

[4] F. Bisotti, M. Gilardi, O.T. Berglihn, R. Tschentscher, L.D. Hansen, S.J. Horn, A. Várnai, B. Wittgens, From laboratory scale to innovative spruce-based biorefinery. Note I: Conceptual process design and simulation, in: F. Manenti, G.V. Reklaitis (Eds.), Computer Aided Chemical Engineering, Elsevier, 2024: pp. 2449–2454. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-28824-1.50409-9.

[5] M. Gilardi, F. Bisotti, O.T. Berglihn, R. Tschentscher, L.D. Hansen, S.J. Horn, A. Várnai, B. Wittgens, From laboratory scale to innovative spruce-based biorefinery. Note II: Preliminary techno-economic assessment, in: F. Manenti, G.V. Reklaitis (Eds.), Computer Aided Chemical Engineering, Elsevier, 2024: pp. 2653–2658. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-28824-1.50443-9.

[6] V. Ballal, M.D. Barbosa Watanabe, M. Gilardi, E.O. Jåstad, P.K. Rørstad, B. Huang, M. Werra, F. Bisotti, B. Wittgens, F. Cherubini, Influence of wood resource types, conversion technologies, and plant size on the climate benefits and costs of advanced biofuels for aviation, shipping and heavy-duty transport, Energy Conversion and Management 327 (2025) 119586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2025.119586.

[7] M. Gilardi, F. Bisotti, O.T. Berglihn, B. Wittgens, CO2 Capture from an Integrated Biorefinery: A Carbon-Negative Path, in: Proceedings of the 17th Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies Conference (GHGT-17) 20-24 October 2024, Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY, 2024. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5016407.

[8] A. Nakao, D. Morlando, H.K. Knuutila, Techno-economic assessment of the multi-absorber approach at an industrial site with multiple CO2 sources, International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 142 (2025) 104326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2025.104326.

[9] B. Lee, H. Lee, J.A. Ningtyas, M. Byun, A. Allamyradov, B. Brigljević, H. Lim, Clustered carbon capture as a technologically and economically viable concept for industrial post-combustion CO2 capture, Energy Conversion and Management 330 (2025) 119608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2025.119608.