2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(75e) Identifying the Ideal Biomass Feedstock for Maximizing Monomer Yield and Resource Efficiency in Reductive Catalytic Fractionation

Authors

Reductive catalytic fractionation (RCF) has been widely researched to convert lignocellulosic biomass into valuable monomers. Currently, highest monomer yield per-gram-lignin can be obtained from RCF of seed coats due to the discovery of catechyl-lignin and its acid-resistant benzodioxane structure. However, other resources in the seed coats are generally unused, leading to low resource efficiency. This study aims to find the optimum biomass feedstock to maximize both monomer yield and resource efficiency in the RCF process. Specifically, the biomass is classified into 5 types based on unique lignin units and chemical compositions: hardwood, softwood, grass, barks, and seed coats. A total of 30 RCF studies were analyzed to compare the monomer yield, carbohydrate retention, and remaining by-products. Highest average resource efficiency was observed in hardwood, softwood, and grass (0.51-0.54 g/g-biomass), compared to barks and seed coats with 0.19-0.29 g/g-biomass, with hardwood producing highest monomer per-gram-biomass (0.09 g/g-biomass).

Keywords: Reductive catalytic fractionation, Lignin, Aromatic monomer, Resource efficiency, Biomass classification

Introduction

Lignocellulosic biomass is a plant material primarily composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, commonly used as a renewable resource for biofuels and bioproducts. Every year, 181.5 billion tons of biomass are generated, out of which only 8.2 billion tons are utilized.1 Various methods have been found to convert biomass into bioenergy and value-added products. Pyrolysis of biomass is a mature technique to produce bio-oil as an energy source and biochar.2 Cellulose and hemicellulose in the biomass can be hydrolyzed into residual sugars, which can subsequently be fermented into bioethanol or other bioproducts. Recently, lignin utilization has also gained popularity, thereby promoting the term “lignin-first biorefinery”. Depolymerization of lignin generates valuable aromatic monomers, which can be used for various applications such as energy source, dyes, and precursor for pharmaceutical applications.3

Reductive Catalytic Fractionation (RCF) is a one-pot thermochemical process to convert biomass into aromatic monomers and oligomers.4 During the process, biomass is fractionated, and lignin is catalytically depolymerized with supplied hydrogen gas or hydrogen donor from organic solvents in a highly pressurized autoclave chamber. RCF generally yields lignin oil, which contains the aromatic monomers dissolved in the organic phase, solid residues, and remaining by-products from decomposition of the cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Being the valuable chemicals, the aromatic monomers are then separated through organic/aqueous extraction and distillations. Meanwhile, the solid residues are tested to determine the carbohydrate retention, which can be enzymatically hydrolyzed into residual sugars for subsequent fermentation into bioethanol or biofuel.

Recent studies on catechyl-lignin (C-lignin) have unveiled that seed coats from vanilla and Melocactus genus are suitable feedstock for RCF due to its high benzodioxane content, e.g., 2D NMR analysis shows that 98% of dimeric units in vanilla is composed of benzodioxane.5 However, seed coats which contains C-lignin is not an abundant feedstock, and only constitutes a small fraction of all available biomass. It is important to optimize not only the monomer yield, but also the resource efficiency to fully utilize the feedstock and minimize waste generation. This study aims to find the optimum biomass which maximizes monomer yield and resource efficiency in the RCF.

Methodology

In this study, we classified the biomass into 5 types based on its unique lignin units and chemical composition, i.e., hardwood, softwood, grass, barks, and seed coats. From a total of 30 RCF studies with the 5 types of biomass, we collected the chemical compositions, monomer yield, carbohydrate retention, and remaining by-product of each RCF reaction in optimized conditions. Then, extensive comparison analysis and mass balance are performed to find the optimum biomass feedstock for RCF in terms of monomer yield and resource efficiency. Resource efficiency in this study is defined as the total mass of usable products, i.e., monomers, oligomers, and carbohydrate retention per gram of biomass feedstock.

Results and Discussion

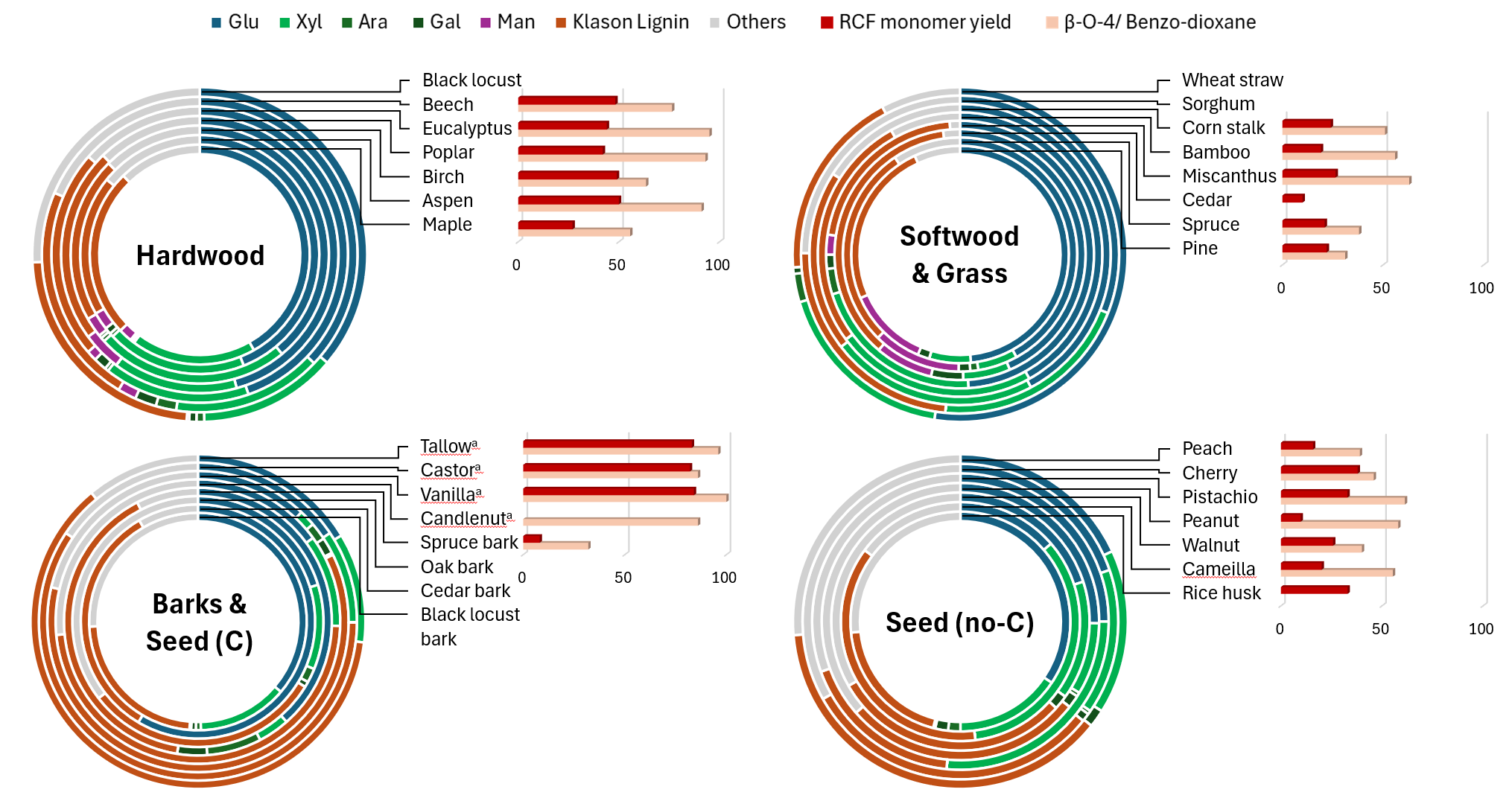

The chemical compositions and β-O-4 / benzodioxane content of the 5 biomass types are compiled in Fig. 1. Typically, hardwood biomass exhibits a simpler and lower hemicellulose content, thereby reducing biological resistance during pretreatment. Despite having relatively low lignin content (18.2-25%), hardwood lignin is characterized by a notably high proportion of β-O-4 linkages (55.6-99.1% of total lignin) and mixture of guaiacyl (G) and syringyl (S) units, indicating considerable potential for depolymerization. As a result, hardwood lignin are promising candidates for RCF process, which depolymerizes lignin to produce aromatic monomers. Meanwhile, softwood typically has higher lignin content, ranging from 24.7% to 36.6%.6-8 The dominant polysaccharide in softwoods is mannose (about 12.1%), with xylan constituting only 6.2%. Softwood lignin tends to have more side-chain structures and a lower proportion of β-O-4 linkages (31.2-38.1%) and high G-units (over 90%). Consequently, direct RCF of softwoods typically results in a higher production of oligomers and lower monomer yields (10-22%), but higher monomer selectivity.9

Grassy biomass differs from woody biomass due to its higher hemicellulose content, which is predominantly in the form of xylan. Their application potential is somewhat limited by the presence of ash (5-10%), which can become incorporated into the lignin structure. Compared to other biomass types, grassy biomass does not exhibit significant advantages in terms of lignin content or β-O-4 linkage composition, but grassy biomass lignin often contains unique aromatic end units, such as p-hydroxybenzoate-lignin, p-coumarate-lignin, ferulate-lignin and tricin-lignin, along with relatively high proportions of H-units.

Barks and seed coats typically have rapid growth cycles and contain relatively low cellulose content, but higher lignin content. However, the lignin content of these materials may be overestimated due to the presence of suberin or other lipid-like compounds, which can be misidentified as Klason lignin using the NREL method.10 Other analysis technique has been performed to prevent this overestimation from the contribution non-lignin compound in Klason lignin determination, e.g., 13C NMR method was established for quantification of lignin in these plant materials. Using this method, the lignin content in vanilla seed coats, which contains almost 100% C-lignin units, decreases from 65.4% to 13% g/g-biomass.11 Through RCF, suberin in barks can be converted into aliphatic monomers with the addition of base catalysts, while C-lignin in seed coats is converted into catechyl monomers.12

Fig. 1. Chemical composition (% g/g-dry-biomass), RCF monomer yield (% g/g-lignin) and β-O-4 / benzodioxanea content (% g/g-lignin) of hardwood, softwood, grass, barks, and seed coats with/without C-lignin. Seed (C) = seed coats with C-lignin; Seed (no-C) = seed coats without C-lignin.

This study aims to determine the optimum feedstock for utilization in large-scale RCF biorefinery. Preliminary mass balance analysis of 13 RCF studies revealed that while seed coats containing C-lignin achieve the highest monomer yield per unit of C-lignin (0.71-0.84 g/g-lignin, as shown in Fig. 1), they exhibit low resource efficiency, producing only 0.29 g of monomer per gram of biomass. The highest average resource efficiency and monomer per-gram-biomass was observed in hardwood, i.e., 0.54 g/g-biomass and 0.09 g/g-biomass, respectively. To improve resource efficiency in seed coats and barks, additional processes may be necessary prior to the RCF to extract the high content of lipid-like compounds.

Further comparison and analysis of each RCF process will be conducted in this study. Aside from monomer yield and resource efficiency, other paramount factors also should be considered when designing a large-scale RCF process. These factors include selectivity and composition of monomers produced, profitability, and energy usage.

References

- N. Singh, R. R. Singhania, P. S. Nigam, C.-D. Dong, A. K. Patel and M. Puri, Bioresour. Technol., 2022, 344, 126415.

- S. Wang, G. Dai, H. Yang and Z. Luo, Prog. Energy Combust. Sci., 2017, 62, 33-86.

- H. Li, A. Bunrit, N. Li and F. Wang, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2020, 49, 3748-3763.

- T. Renders, G. Van den Bossche, T. Vangeel, K. Van Aelst and B. Sels, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., 2019, 56, 193-201.

- F. Chen, Y. Tobimatsu, D. Havkin-Frenkel, R. A. Dixon and J. Ralph, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012, 109, 1772-1777.

- J.-X. Wang, S. Asano, S. Kudo and J.-i. Hayashi, ACS Omega, 2020, 5, 29168-29176.

- Z. Wang, S. Winestrand, T. Gillgren and L. J. Jönsson, Biomass & Bioenergy, 2018, 109, 125-134.

- Y. Yamashita, C. Sasaki and Y. Nakamura, J. Biosci. Bioeng., 2010, 110, 79-86.

- J. Lupoi, S. Singh, R. Parthasarathi, B. Simmons and R. Henry, Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev., 2015, 49.

- M. M. Abu-Omar, K. Barta, G. T. Beckham, J. S. Luterbacher, J. Ralph, R. Rinaldi, Y. Román-Leshkov, J. S. M. Samec, B. F. Sels and F. Wang, Energy & Environmental Science, 2021, 14, 262-292.

- Y. Li, L. Shuai, H. Kim, A. H. Motagamwala, J. K. Mobley, F. Yue, Y. Tobimatsu, D. Havkin-Frenkel, F. Chen, R. A. Dixon, J. S. Luterbacher, J. A. Dumesic and J. Ralph, Science Advances, 2018, 4, eaau2968.

- D. M. Neiva, M. Ek, B. F. Sels and J. S. M. Samec, Chem Catalysis, 2024, 4.