2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(551f) Exploring Microbial Collective Dynamics Using Bioprinting and Biomaterials Approaches

Author

For decades, biomaterials and tissue engineers have focused on creating hydrogel biomaterials with tunable physical and chemical properties, enabling the study of mammalian cell behavior within biomedically relevant models. The emergence of bioprinting has further revolutionized this field, enabling the fabrication of sophisticated in vitro 3D models that mimic the complexity of living tissues. This leap raises an exciting opportunity: Can these advancements in emerging biomaterials approaches be applied to investigate the collective dynamics of microbial communities? Such advancements would have implications across biomedical and environmental engineering, such as studying microbial infection dynamics and bioremediation in polluted soils, both of which heavily rely on microbial collective growth and migration in complex three-dimensional environments.

In this work, we aim to bridge the fields of biomaterials engineering, bioprinting, and microbial research to address this question. We have designed microporous, chemically modified biopolymer hydrogels with precisely tunable porosity and stiffness at biologically relevant scales. These granular hydrogels consist of hydrogel microparticle building blocks, or “microgels”, that are assembled into a jammed state to form a soft granular medium. The granular structure allows for flowability, injectability, and printability, while the void space between microgels creates microscale porosity for investigating cell movement. Microgel building blocks can also be mixed and patterned to further enhance material functionality. These materials are transparent, which allows us to “spy” on cells in microporous habitats, much like the environments they live in like tissues and soil.

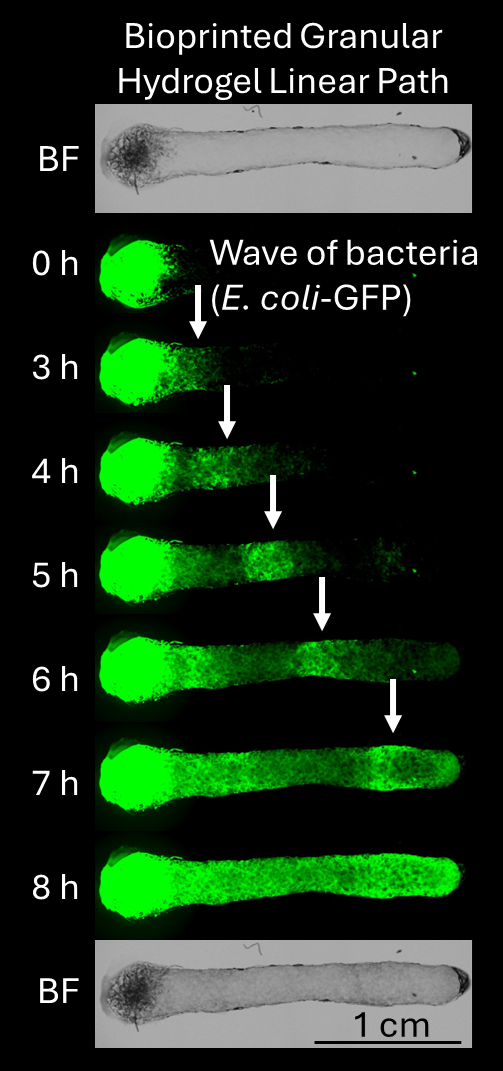

Leveraging bioprinting techniques, we create complex pathways to study Escherichia coli (E. coli) collective migration and growth in real time through time-lapse imaging as a model system. We create granular hydrogels from photocrosslinkable biopolymer (e.g., hyaluronic acid, gelatin, and alginate) microgels assembled into a jammed state, with pore sizes ranging from 1-100 microns and storage moduli (G’) on the order of ~100-1000 Pa. Using an extrusion bioprinter, we create complex pathways with twists, turns, bends, and obstacles. We inoculate a dense colony of microbes on one end and use time lapse imaging to investigate the impact of local microenvironmental properties (e.g., porosity, stiffness, pore interconnectivity) and path geometry (e.g., constrictions, expansions, bends) on the speed and behavior of migrating microbes.

An example of this approach is shown in Figure 1. We create a bioprinted linear path of granular hydrogel made from hyaluronic acid microgels that are fragmented polygons in shape, with a pore size on the order of 10-10 microns and a total void space of ~10-20%, which mimics biophysical confinement in many tissues and soil systems. Initial and end paths are shown in bright field (“BF”). E. coli that express GFP are inoculated on one end. Over 8 hours, the microbes collectively migrate in “waves” across the microporous environment in response to oxygen, nutrient, and chemoattractant gradients. Experiments are held at 30°C. We observe collective microbial behavior using fluorescence imaging (green signal).

In future work, we plan to integrate these experiments with theoretical modelling to further understand underlying biophysics. In addition, we seek to explore the impact of mammalian host cells and pathogenic bacteriophages (i.e., viruses that infect bacteria) on microbial dynamics in microporous, bioprinted environments. These are exciting directions that our new and growing lab seeks to pursue over the next year.

By advancing the methodologies for engineering microbial microenvironments and applying emerging biomaterials technology, this research not only provides new tools for microbial dynamics research but also opens pathways to broader applications, such as antimicrobial drug development, synthetic microbial ecosystems, and ecological studies.