2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(679f) Exploring Disjunctive Programming Formulations for Optimal Design of Distillation Columns

Authors

Automating process synthesis presents a formidable challenge in chemical engineering. Developing frameworks that are both general and accurate – while remaining computationally tractable – is particularly demanding. To further increase the solvable problem size, an advanced optimization framework is proposed, leveraging Generalized Disjunctive Programming (GDP) for process synthesis and design problems. This framework allows for multiple improvements over existing Mixed Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) formulations, aiming to enhance feasibility and reduce solution time.

Process synthesis problems are typically posed as nonlinear optimization problems with continuous and discrete variables. Traditionally, these are formulated as MINLP problems, where discrete variables appear as integer or binary variables. These are usually relaxed to continuous variables to solve the MINLP.

In practice, the (in-)equality constraints are obtained starting from logical expressions, which are reformulated as algebraic constraints. Disjunctive expressions are typically converted into mixed integer constraints by using “big-M” constraints [1]. An alternative reformulation for treating disjunctions is the convex hull (chull) formulation, which achieves superior relaxation tightness but is rarely used due to its greater complexity and potential numerical difficulties [2].

Recent advances in GDP allow for automatic reformulation of optimization problems, e.g., by big-M or chull. Furthermore, dedicated GDP solution algorithms are now available [3]. Unlike conventional Branch and Bound or Outer Approximation algorithms, their logic-based counterparts can neglect inactive equations, reducing the size and complexity of subproblems. This is achieved by deactivating unused model equations during the solution procedure, as shown by Lee et al. [4].

This point is particularly interesting for chemical engineering, as a lot of time is spent computing NLP subproblems. Also, model formulation can have a large impact on the solution times of MINLP [1]. However, evaluating various model formulations tends to be rather tedious. Especially detailed model formulations that include rigorous thermodynamics and kinetics tend to increase the model size significantly. As a first step for further exploitation of GDP for process synthesis and process design, we developed a modeling environment and automatic code generation framework for GDP. This contribution aims at investigating different problem formulations for GDP in process design facilitated by the new framework.

Methodology

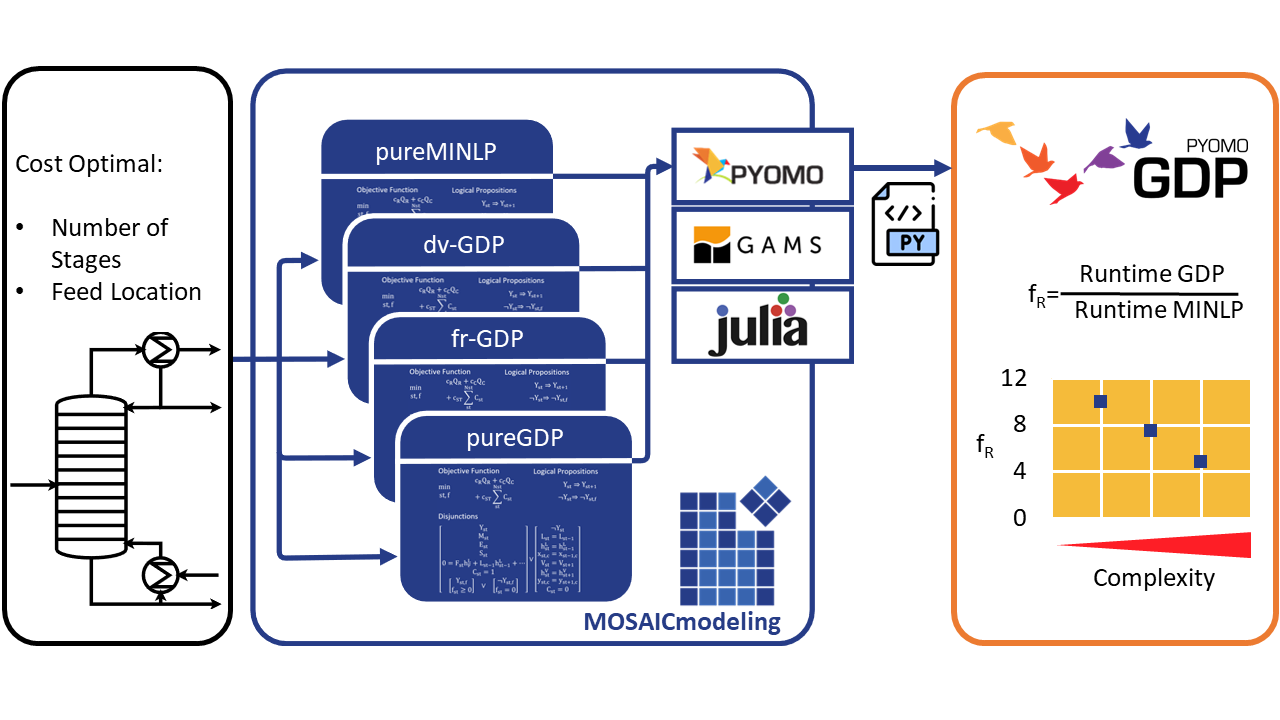

For maximum flexibility and independence from any given programming language, the modeling and problem formulation is implemented within MOSAICmodeling [5], a platform that allows for model formulation at the documentation level. Users formulate equations in LaTeX, which are then translated into MathML/XML preserving all relevant information while remaining as general as possible. The first step hereby consists in the definition of a suitable notation. This defines all possibly occurring variables and their indices and sets the basis of all MathML/XML operations. To include GDP into this workflow, already existing variable definitions were extended to also include logical / Boolean variables. Equations are created based on those extended notations: Basic logical operators – and (∧), or (∨), not (¬), implication (⇒), and equivalence (⇔) – were added to include logical expressions. Furthermore, disjunctions can be created by linking Boolean variables with single equations or sets of equations. The resulting systems defined in MathML/XML can be exported to any programming language using MOSAICmodeling’s UDLS feature [6], which has been extended tocapture connections between disjunctive, logical variables, and their associated equations, allowing for code export to GAMS, Julia, and Pyomo.

Four different MINLP/GDP formulations were implemented in MathML/XML in MOSAICmodeling, exported, and evaluated within pyomo regarding their benefits in optimizing thermal separation problems. For this case study, the MINLP formulation of Kraemer et al. [7] is evaluated (pureMINLP), which determines the optimal column height to achieve desired product specifications while minimizing costs for a multicomponent distillation column. The MINLP formulation varies locations of feed, reflux, and boilup streams. Each separation stage is modeled rigorously applying thermodynamics of varying complexity.

An alternative, GDP formulation (pureGDP) specifies disjunctions for each separation stage as in [QGrossmann2000rig]. The disjunctive variables decide which stages are active or not. For active stages, the stage formulation is the same as above. For inactive stages, a passthrough of liquid and vapor streams without thermodynamic calculations is applied. The feed location is modeled as a nested disjunction for the active stages.

Two additional formulations, in between pureMINLP and pureGDP, apply different levels of relaxation: Feed relaxed GDP (fr-GDP) employs the disjunctive formulation for the stages, while applying pureMINLP’s formulation for the feed location. Decision variable GDP (dv-GDP) on the other hand, applies a formulation that translates directly into the pureMINLP formulation if the dv-GDP is relaxed by BigM and the M is chosen accordingly.

The four different MINLP/GDP formulations are combined with two different implementations for thermodynamics calls: (1) explicit formulation using the Antoine equation for vapor pressures, linearized heats of evaporation, and constant specific heat capacities; (2) external thermodynamic function calls using a CAPE-OPEN interface with TEA as thermodynamics engine [8]. Note that the same thermodynamic models are used for explicit and external thermodynamics implementations to ensure comparability of the solutions. However, the interface supports any CAPE-OPEN compliant thermodynamics engine, allowing for even highly complex equations of state, such as, PC-SAFT. Future work will therefore also include non-idealities, which is not in scope of this contribution.

To evaluate the performance of available GDP solvers, the formulations in MathML/XML are exported to pyomo. Exports to julia and GAMS were also developed. However, they currently lack support for dedicated GDP solvers.

Results

Three cases were investigated with respect to runtime until an optimal solution was found: a column with up to 10 stages and internal thermodynamics, up to 10 stages and external thermodynamics, and up to 20 stages and external thermodynamics. For comparison, the runtime of the GDP problems (pureGDP, fr-GDP, dv-GDP) is given relative to the runtime of pureMINLP’s solution. This indicates the additional time that the GDP formulations require for each respective case. The optimal solution always shows 8 active stages with the feed located on the 5th stage from above. The results of the case study for the best performing GDP formulation are shown in the figure below.

We discovered that all GDP formulations perform worse than the pureMINLP formulation. However, some formulations outperform others. Although the runtime of the best-performing GDP formulation (fr-GDP) consistently exceeds that of the MINLP formulation, the relative runtime surplus / difference decreases as system complexity increases. This is important as future problems, especially synthesis problems, will be a lot more complex than this study. Seeing that the runtime for (fr-GDP) scales better with increasing complexity, we assume that GDP formulations may be beneficial for larger process synthesis problems.

This study also shows that simply transforming an MINLP formulation into a GDP does not necessarily yield benefits. Runtime strongly varies across the three GDP formulations. To this end, further investigations for efficient exploitation of GDP for process synthesis is required. Our modeling framework in MathML/XML now supports fast formulation of highly complex GDPs and evaluation in a variety of supporting platforms (pyomo, julia, GAMS), speeding up the process of tailoring problem formulations.

The investigated problem sizes are small, chosen as a proof of concept for formulation, code generation, and solution of GDPs. Given the runtime of the investigated problems, increasing system size is feasible. Future work will aim to increase the total system size and move towards more general process synthesis, potentially putting GDP problem runtime below that of relaxed MINLP.

References

[1] L. T. Biegler, I. E. Grossmann und A. W. Westerberg, Systematic Methods of Chemical Process Design, 1997.

[2] N. W. Sawaya and G. I. E., "Computational implementation of non-linear convex hull reformulation," Computers & Chemical Engineering, vol. 31, no. 7, pp. 856-866, 200

[3] Q. Chen, E. S. Johnson, J. D. Siirola und I. E. Grossmann, „Pyomo.GDP: Disjunctive Models in Python,“ Computer Aided Chemical Engineering, Bd. 44, pp. 889-894, 2018.

[4] S. Lee und I. E. Grossmann, „New algorithms for nonlinear generalized disjunctive programming,“ Computers & Chemical Engineering, Bd. 24, Nr. 9-10, pp. 2125-2141, 2000.

[5] E. Esche, C. Hoffmann, M. Illner, D. Müller, S. Fillinger, G. Tolksdorf, H. Bonart, G. Wozny und J. Repke, „MOSAIC – Enabling Large‐Scale Equation‐Based Flow Sheet Optimization,“ Chemie Ingenieur Technik, Bd. 89, Nr. 5, p. 620–635, 2017.

[6] G. Tolksdorf, E. Esche, G. Wozny und J.-U. Repke, „Customized code generation based on user specifications for simulation and optimization,“ Computers & Chemical Engineering, Bd. 121, pp. 670-684, 2019.

[7] K. Kraemer, S. Kossack und W. Marquardt, „Efficient Optimization-Based Design of Distillation Processes for Homogeneous Azeotropic Mixtures,“ Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, Bd. 48, Nr. 14, p. 6749–6764, 2009.

[8] J. Baten, R. Taylor und H. Kooijman, „Using Chemsep, COCO and other modeling tools for versatility in custom process modeling,“ AIChE Annual Meeting, Conference Proceedings, 2010.