2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(291c) Experimental Micro Scale Insights into Particle Collision Dynamics under Dry and Wet Conditions

Authors

1. Introduction

In the chemical, pharmaceutical and food industries, a wide variety of different processes are used that include granular materials. In the case of fluidized bed systems, spray dryers, solids mixers or pneumatic solids transport, for example, the processes are strongly characterized by collisions and interactions between the particles. The particles can either be dry or, as in the case of fluidized bed spray agglomeration, moistened. These dry or wet collision interactions influence both the process itself, e.g. through abrasion or increased caking, and the product, e.g. through agglomeration. Reliable simulation of such solids processes is extremely important in order to avoid undesired effects and to control desired effects. The most frequently used simulation method for particle interactions on the apparatus scale is the Discrete Element Method (DEM). The particles (the discrete elements) are often assumed to be ideal spheres. Their motion is determined by the forces acting on them according to Newton's equations of motion. Various contact models exist to determine the forces acting in collisions of cohesionless particles, such as the Hertz-Mindlin approach according to Tsuji et al. [1] which is frequently used in DEM. However, the ability of such models to correctly reproduce the motion of particles after a collision has so far lacked valid experimental evidence. In order to check the validity of the contact models, collision experiments between spherical, dry particles are compared with DEM model predictions in this contribution. In order to determine the influence of additional liquid on the collision outcome, comparative data from collision experiments between wetted spherical particles are shown as well.

2. Experimental setup and procedure

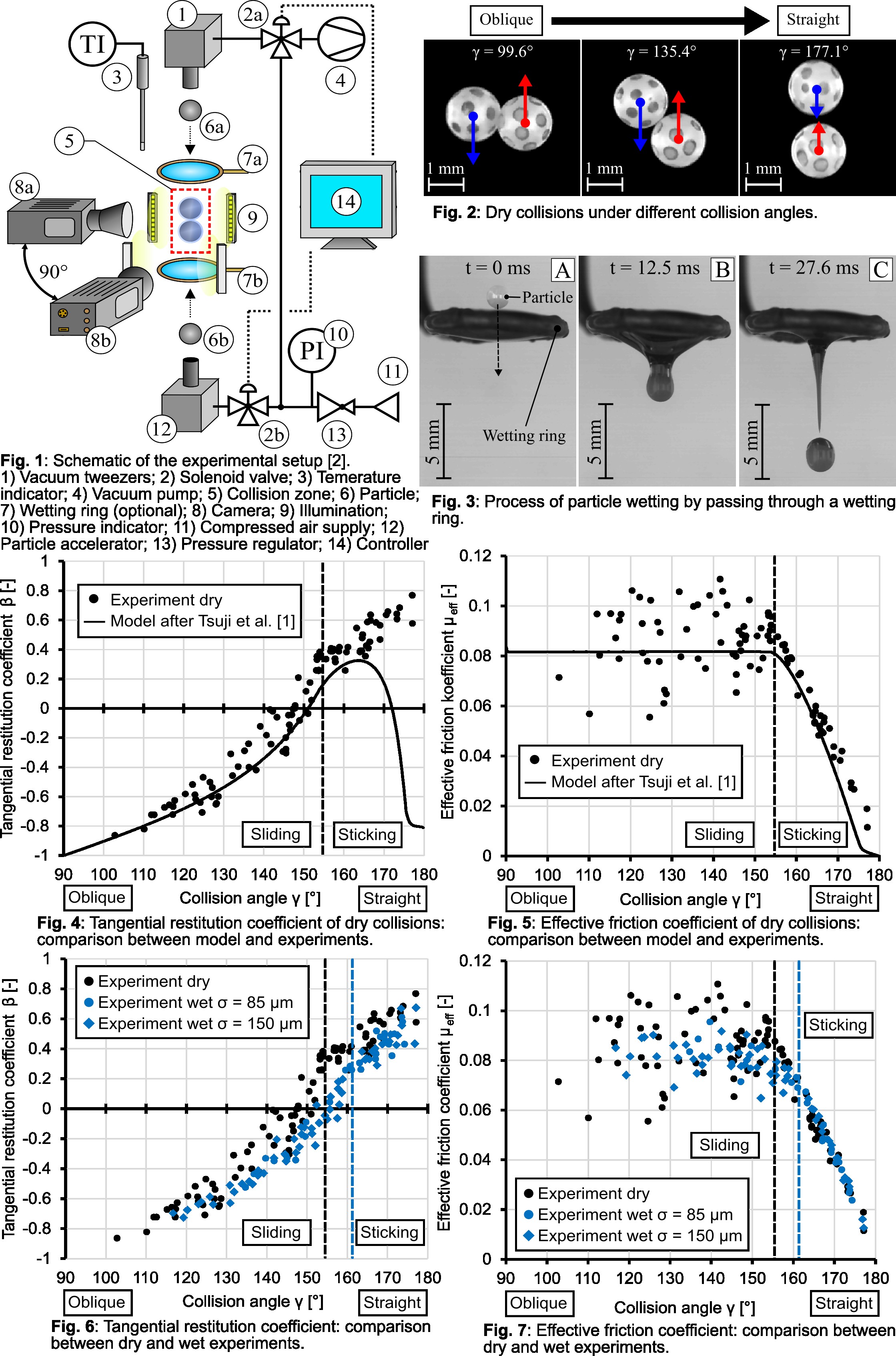

The experimental setup for performing free interparticle collisions is shown schematically in Figure 1. One particle is held in the upper position by an applied vacuum on a thin tube, the so-called vacuum tweezers. The vacuum is broken by actuating a solenoid valve, whereupon the particle falls down. The second particle is shot vertically from the bottom upwards towards the first particle by the so-called particle accelerator. The timing of the activation of the vacuum tweezers and particle accelerator is coordinated by the control system so that both particles collide in the field of view of two high-speed cameras. The high-speed cameras are horizontally offset by 90° in order to capture the movement of the particles in three dimensions. For the experiments, the particles are brought into collision at different collision angles γ, from very oblique (γ = 90°) to very straight (γ = 180°), as shown in Figure 2.

For wetted collision experiments, so-called wetting rings can be positioned in the trajectory of the particles before the particles collide. A wetting ring is a copper wire ring, which is dipped into the liquid to be applied to the particles before the experiment. When the ring is removed from the liquid, a film of liquid remains in the ring. If the particles pass through this film, they are completely wetted, as shown in Figure 3.

The movement data of the particles is extracted from the images taken of the collisions using specially developed methods of digital image analysis. This includes both the translational movement as well as the direction and speed of rotation in three-dimensional space. For rotation detection, the particles are provided with dot-shaped rotation markers. In the case of wetted collisions, the images are also used to analyze the thickness of the liquid layer on the particles. Based on the movement and liquid data, characteristic values of the collision are determined, such as the restitution coefficients in the normal and tangential directions. For further and more detailed information, the authors refer to the publications of Bunke et al. [2].

3. Materials

The particles used are high-precision ball bearing beads made of yttrium-stabilized zirconium oxide with a diameter of 1.5 mm. Zirconium oxide has a density of 6000 kg/m3, a Youngs' modulus of 210 GPa and a hardness of 89 HRa. The surface of the spheres is polished and therefore has a low roughness of Ra = 0.03 µm and Rz = 0.2 µm.

A silicone oil with a dynamic viscosity of 18.9 mPas, a density of 945 kg/m3 and a surface tension of 20.6 mN/m (at 25°C) is used for wetted collisions.

4. Results

The focus of this contribution is on the consideration of the tangential restitution coefficient β. In contrast to the frequently investigated coefficient of restitution in the normal direction, not only the translational movement of the collision partners is included, but also their rotation. This makes a precise measurement of β significantly more difficult. As a result, β is insufficiently investigated in the existing literature. Only the combination of a novel experimental setup in conjunction with improved image analysis methods provides reliable measurements.

The data points in Figure 4 show the experimentally determined curve of β for dry collisions plotted against γ. The curve of β starts with very oblique collisions (γ close to 90°) at negative values close to -1 and increases with increasing γ (increasingly straighter collisions) until it reaches the positive range. The gradient increases steadily up to the so-called collision limit angle γlim of approx. 155°. From there, the curve flattens out to a smaller, linear increase. The reason for the change in the curve is the transition from the slipping contact regime for oblique collisions to the sticking contact regime for straight collisions. In the sticking contact regime with relatively large collision angles, the tangential forces are not limited by the friction between the particle surfaces. With more oblique collisions, i.e. with decreasing γ, the tangential forces become so large that the friction between the particle surfaces is no longer sufficient and the particle surfaces start to slide. The tangential forces are limited here by Coloumb's law of friction. This transition from the sliding to the sticking contact regime is clearly visible in Figure 5, in which the measured effective coefficient of friction µeff is plotted against the collision angle. µeff is the ratio of tangential to normally transmitted momentum. It is zero for an exactly straight impact. As γ decreases, it initially increases almost linear up to γlim of 155°. From there, the value remains constant, which corresponds to the coefficient of sliding friction of the material pairing.

In direct comparison to the measurements, Figure 4 and 5 also show the theoretical curve of the parameter-adapted model according to Tsuji et al. [1]. The differences between experiment and model prediction can be seen most clearly in the plot of β. While the measurements in the sliding contact regime can be reproduced by the model to an acceptable extent, the model prediction fails in the sticking contact regime. The model predicts a re-drop of β far into the negative region, while the measurements all remain positive.

The comparison between dry and wet collisions is shown in Figure 6 and 7. In the wetted experiments, only one particle was wetted, the other remained dry. Two different liquid layer thicknesses were applied to the wetted particle, one 85±14 µm and the other 150±10 µm. The collision speed was kept constant in both series of experiments and was chosen high enough so that agglomeration could be excluded. It is noticeable that there are differences in β and µeff between dry and wet collisions, but no significant differences can be identified between the wet series of experiments. The wetted collisions show a very similar curve for β over γ, but the curve is shifted towards larger collision angles. This shift can be attributed to reduced friction due to the lubricating effect of the liquid between the particle surfaces. This friction reduction in wetted collisions can also be seen in Figure 7 on the basis of µeff. On the one hand, the mean value in the slipping contact regime is below that of the dry collisions. On the other hand, the transition from the sticking to the sliding contact regime already occurs with straighter collisions so γlim changes from 155° for dry to 162° for wetted collisions.

5. Conclusion

Despite the use of an almost ideal model system consisting of cohesionless, almost ideally elastic, highly precisely manufactured, spherical particles, the comparison between measurement and model of the tangential restitution coefficient in dry collisions shows a clear, systematic deviation in the adhesive contact regime. This indicates an incorrect tangential force calculation in the investigated contact force model according to Tsuji et al. [1]. DEM simulations using this model are therefore not able to correctly reproduce the actual particle movement after a collision.

In addition, the lubricating effect in a wet collision was demonstrated and its effects on the curves of the tangential coefficient of restitution and the effective coefficient of friction were identified.

6. Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the German Research Foundation (DFG) for funding the research via HE 4526/28-3.

- References

[1] Y. Tsuji, T. Tanaka, T. Ishida, Lagrangian numerical simulation of plug flow of cohesionless particles in a horizontal pipe, Powder Technology 71 (1992) 239–250.

[2] F. Bunke, S. Pietsch-Braune, S. Heinrich, Three-dimensional measurement method of binary particle collisions under dry and wet conditions, Chemical Engineering Journal 489 (2024) 151016.