2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(515f) Experimental and Computational Studies on Functionalized Lignin-Containing Cellulose (FLCNC) for PFAS Adsorption from Water

Authors

Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) are environmentally persistent chemicals that have raised concern worldwide in recent years because of their widespread use, related harmful effects on human health and bioaccumulation in the environment. Some of the most abundant PFAS are PFOA and PFOS, listed by the IARC as carcinogenic (PFOA) or possibly carcinogenic to humans (PFOS), and associated with multiple organ affections [1]. Hence, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has established Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCL) for some PFAS in drinking water (e.g. 4 ng L-1 for PFOA and PFOS), and research on the development of materials, technologies, and treatments to address PFAS contamination is highly sought worldwide.

PFAS are challenging targets for remediation due to their ubiquity and multiple highly stable C-F bonds that provide them with a highly stable chemical structure, which is very resistant to degradation. In water treatment, efforts have been orientated at either the removal or destruction of PFAS or a combination of both. Among the currently used methods for removal, adsorption is conspicuous for its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and straightforwardness since it consists of a superficial physical or chemical interaction between a fluid phase component and a solid surface [2].

Many adsorbents have been proposed and evaluated, but there is still a need to improve the design and development of sustainable, high-performance materials for PFAS adsorption processes. Cellulose is an appealing raw material for adsorbent fabrication. It is the most abundant natural polysaccharide, and its chemical structure, with numerous hydroxyl groups, provides versatility towards chemical modifications [2]. This work aims to assess the efficiency of functionalized lignin-containing nanocellulose (FLCNC) as an adsorbent for PFAS in water systems and achieve a safe level for drinking water (< 4 ng L-1), introducing positively charged groups in the cellulose to interact with the negatively charged PFAS. To support this effort, computational modeling based on DFT simulations is conducted to elucidate the mechanisms involved in the binding of PFAS to FLCNC and identify the positioning of the molecules.

Experimental details

Adsorbent Fabrication and characterization

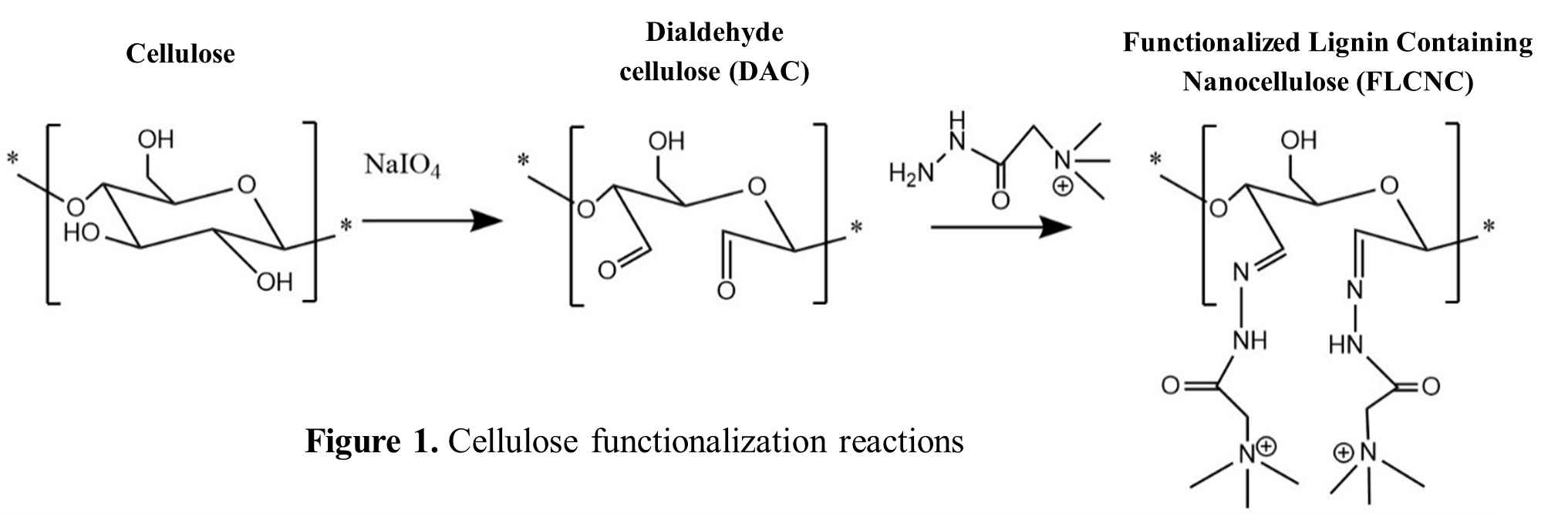

Cellulose pulp was obtained from pine by extractions with a Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES, choline chloride : ethylene glycol : p-Toluene sulfonic acid) and propylene carbonate. The pulp was then oxidized with NaIO4 to yield dialdehyde cellulose (DAC), which was subsequently reacted with an hydrazide (Girard’ T reagent, acidic conditions,70 °C,1 h) to yield FLCNC containing quaternary ammonium groups(Figure 1)[2], followed by washing and freeze-drying. The aldehyde group contents of DAC were determined by the quantitative reaction of hydroxylamine hydrochloride and aldehyde group, and the released HCl thus could be titrated by an equivalent NaOH solution according to the equation: -CHO + NH2OH.HCl à -CHNOH + HCl + H2O[3].

The cationic group content of the FLCNC was calculated from the nitrogen content determined by elemental analysis (TNTplus 880 s-TKN).

FT-IR spectra of the unmodified LCNC (control) and the FLCNC were collected in ATR mode (Nicolet 4700 ThermoFisher Scientific) to confirm the presence of the hydrazone in the FLCNC. The adsorbent's surface charge at different pH levels (4, 6, 8, 10) was measured (ZetaSizer Nano ZS—Malvern Instruments). XRD was performed in a Rigaku Ultima IV X-ray diffractometer. The specific surface and pore size of FLCNC and LCNC are determined by N2 adsorption-desorption analysis (Micrometrics ASAP 2020, BET method).

Adsorption studies – Batch assays

In the kinetics studies, 10 mg of FLCNC is added to 100 mL of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) or perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) solution (5 ug L−1) at pH 6. Then, the mixtures are shaken at 150 rpm at 20°C. Aliquots are taken at specific times (0, 10, 20, 30, 45, 60, 120, 180 min and 24 h. To investigate the adsorption equilibrium, adsorption isotherms were obtained. For these experiments, 10 mg of FLCNC in its freeze-dried form is added to 100 mL of PFOA or PFOS solutions with specific concentrations (0.6, 1.2, 3, 6, 12, and 18 ug L−1) at pH 6, and shaken at 150 rpm at 20|°C for 3 h.

For both kinetics and isotherm studies, the supernatants are filtered for PFOA or PFOS concentration determination by UHPLC-MS/MS, as detailed next. The experimental data for both kinetic and isotherm assays were modeled using well-known equations of adsorption isotherms by nonlinear fit using OriginPro 2023b software.

Adsorption studies - Analytical techniques

PFOA and PFOS solutions were prepared using isotopes: Potassium perfluoro-1-octanesulfonate (PFOS) (¹³C₈, 99%) and Perfluoro-n-octanoic acid (PFOA) (¹³C₈, 99%, respectively (Cambridge isotopes). Their concentrations were determined using a UHPLC (Waters, Milford) coupled with an XEVO TQ-XS tandem mass spectrometer (UHPLC-MS/MS, Waters - MassLynx 4.2) equipped with an ESI source and operated in negative ion mode, with a CORTECS® C18+ analytical column (1.6 µm, 100 mm x 2.1 mm) connected to CORTECS® UPLC C18 VanGuard Pre-column (1.6 µm, 5 mm x 2.1 mm). All studies were conducted in duplicate.

Computational Modeling methodology

Computational studies were conducted for PFOA and PFOS, to analyze the effect of the different PFAS heads on the adsorption mechanism using DFT- B3LYP/6-311++G(2d,2p) level of theory in Gaussian 09W software, using SMD (Solvent Model Density) for water. First, the geometries of the adsorbate, adsorbent, and cluster were optimized, and then the binding energy was calculated as: DEbinding = Ecluster – (Eadsorbate + Eadsorbent). Gibbs free energy (DG) is obtained as well.

Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) surfaces were plotted to identify the areas with lower electron density (electrophilic regions), and the positioning of the anionic PFAS on the surface to evaluate the adsorption strength, represented by DEbinding. Additionally, the DG was calculated to assess whether the positioning of the PFOA (or PFOS) on the proposed FLCNC site is in alignment with a binding interaction (when DG <0) [4]. Results of the modeling are currently being analyzed.

Results & discussion

The aldehyde content of the intermediate product is 3.3 mmol/g, and cellulose’s quaternary ammonium group content was 0.373 mmol g-1. The presence of the acyl hydrazone in the FLCNC was confirmed by the FT-IR spectrum bands at 1567 (n C=N), 1693 (n C=O), and 924 (n N-N). FLCNC exhibited a positive Z potential at the pH level lower than 6 (~ 40 mV), while at the pH above that, the Z potential decreased until reaching a value of about 0 mV at pH~10. These results suggested the positively charged adsorbent should be more efficient for PFAS removal at pH~6. XRD results showed the decreased crystallinity index (CI) of functionalized cellulose compared to the pristine one (84% in LCNC vs. 67% in FLCNC), which is in agreement with the introduction of the functional groups in the FLCNC, which partially disrupt the original H-bonds in cellulose [5].

The adsorption mechanisms were investigated through fitting the experimental data of the kinetic assays for PFOA with pseudo-first and pseudo-second-order models. According to the adjusted determination coefficient (Radj2= 0.987), the pseudo-second-order model was the best fit when plotting the adsorption uptake (qt) at time t (𝑞𝑡=𝑞max⋅𝑘2⋅𝑡/1+𝑞max⋅𝑘2⋅𝑡), with maximum adsorption capacity of qmax= 21.09 ± 0.42 μg g−1, and kinetic constant k2= 0.0222 ± 0.003 g μg−1 min−1 for PFOA. This indicated that adsorbate interactions mainly control the kinetics for the adsorption mechanism, which is in agreement with strong electrostatic interactions between the PFOA and the positively charged amino groups of the FLCNC governing the adsorption mechanism. Analogous results are expected for PFOS.

Adsorption isotherms were constructed by plotting the amount of pollutant retained on the adsorbents, qe, against the supernatant’s concentration under equilibrium (Ce), at room temperature. The parameters of the models as well as the adjusted determination coefficient (Radj2) showed that the best fit to the data is given by the Langmuir equation (qe=(qmax*kL**Ce)⁄(1+ kL*Ce)), and the values obtained are consistent with a favorable PFOA adsorption process onto the FLCNC (qmax = 26.32 ± 2.49 [μg g-1], kL= 0.32 ± 0.08 L-1μg-1], Radj2= 0.94), achieving an ~ 80% PFOA removal efficiency for FLCNC in 2 hours. Analogous studies are being conducted for PFOS, to compare the removal efficiency.

The geometry optimization of individual compounds (FLCNC, PFOA, and PFOS) was conducted, and ongoing work is focused on the clusters’ optimization to obtain the binding energy in each case and determine the positioning that will help better understand the adsorption, as mentioned before.

Conclusions

Preliminary results from this ongoing research showed the enormous potential of FLCNC as an efficient PFOA adsorbent, achieving final concentrations that meet drinking water standards, and contributing to the sustainable development of materials and technologies for water treatment. The combination of molecular modeling and experimental work provides new insights into the adsorption mechanisms of PFAS, to guide the development of advanced, sustainable materials for water treatment.

[1] K. Steenland, A. Winquist, Environ. Res. 2021, 194, 110690.

[2] H. Liimatainen, T. Suopajärvi, J. Sirviö, O. Hormi, J. Niinimäki, Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 103, 187-192.

[3] D. Yang, V. Kumar, Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 90, 1486-1493.

[4] A. K. Ilango, P. Arathala, R. A. Musah, Y. Liang, Water Res. 2024, 255, 121458.

[5] R. O. Almeida, T. C. Maloney, J. A. F. Gamelas, Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 199, 116583.