2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(541a) Engineering a Next-Generation Vaccine: Targeting Pneumococcal Disease in an Aging Population

Authors

Due to the deadly nature of pneumococcal disease and more specifically pneumococcal pneumonia, many efforts have been taken to combat this disease with one of the most effective measures being vaccination. Typical vaccines for pneumococcal disease are based on the capsular polysaccharide that coats S. pneumoniae bacteria. Some vaccines that utilize this polysaccharide are the pneumococcal conjugate vaccines including PCV13, PCV15, PCV20, and PCV21, and the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, PPSV23. Both PPSV23 and PCV13 have moderate efficacy in non-elderly populations against pneumococcal pneumonia; however, the elderly population has a markedly lower vaccine efficacy with PPV23 having a 33% efficacy against pneumococcal pneumonia and PCV13 having a 45% efficacy against pneumococcal pneumonia [6, 7].

To improve upon this, our group has developed a new approach to pneumococcal pneumonia vaccination with a particular focus on older populations. In our approach, we use a lipid nanoparticle as the delivery vehicle for two distinct pneumococcal antigens. Foundational logic for this delivery approach is the co-localization of two types of antigens within the lipid nanoparticle framework, thus, mimicking polyconjugate vaccines, like PCV13, which have shown the best clinical responses to pneumococcal disease. The approach also delivers antigens that coincide with different stages of disease progression. This lipid nanoparticle vaccine has been termed Liposomal Encapsulation of Polysaccharide (LEPS). The current formulation of the LEPS vaccine consists of one polysaccharide antigen from the pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide (CPS) of S. pneumoniae located in the aqueous core of the lipid nanoparticle and a second surface-exposed S. pneumoniae protein antigen, recombinantly produced, attached to the surface of the lipid nanoparticle.

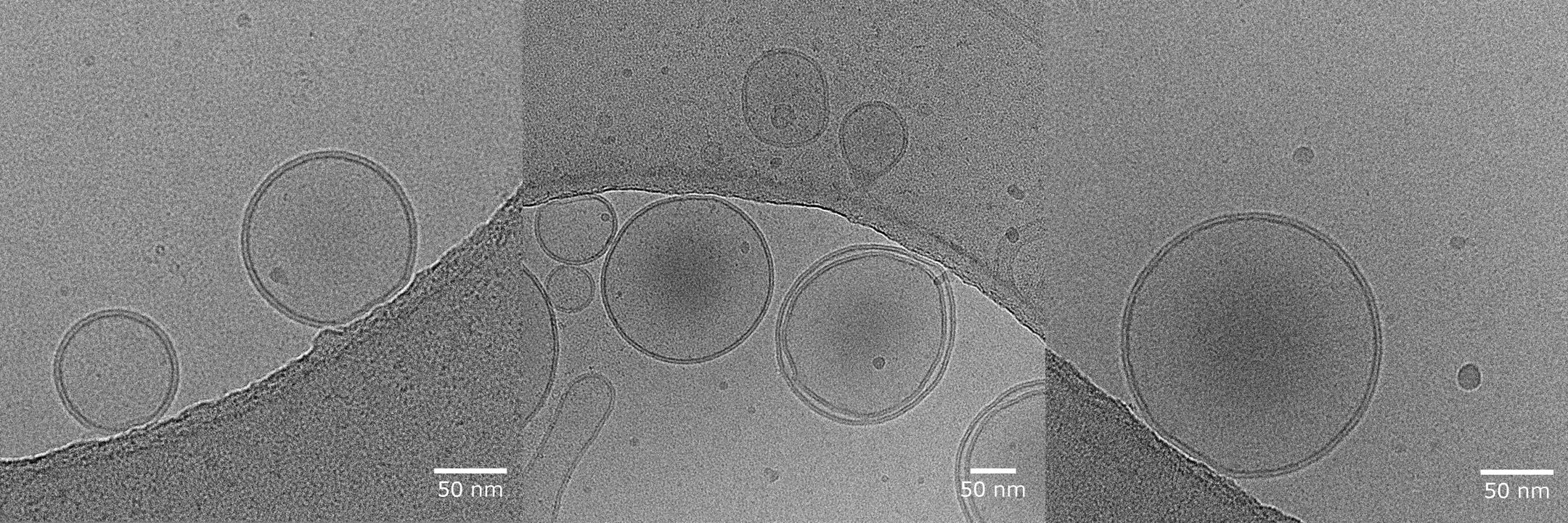

Using a range of experimental techniques that span vaccine delivery vehicle formulation and in vivo immune response characterization, our LEPS approach has demonstrated protection in aged mice subjects. Typical LEPS particles show an average diameter of 182 nm with an average polydispersity index of 0.129 and an average surface charge of -12 mV, while capable of 79% encapsulation efficiency of CPS and 75% surface attachment efficiency of protein antigen. Importantly, when tested as a vaccine carrier to both young and aged mice subjects, we see protection provided by LEPS in both subject cohorts, in contrast to limited protection provided by PCV13 in the aged mice subjects. Recent experiments have shown that our LEPS formulation confers higher protection against S. pneumoniae challenge in mice when compared to PCV13.

The LEPS vaccine formulation represents a promising advancement in pneumococcal pneumonia prevention, particularly for vulnerable elderly populations. By utilizing lipid nanoparticle delivery to co-localize two pneumococcal antigens, LEPS mimics the effectiveness of polyconjugate vaccines while enhancing protection through a dual-stage antigen approach. Our results demonstrate that LEPS provides superior protection against pneumococcal disease in aged mice compared to current vaccines like PCV13, suggesting a potential for greater clinical efficacy in elderly individuals. This novel vaccine strategy offers a compelling avenue for further development and testing, with the potential to reduce the burden of pneumococcal disease in high-risk populations globally.

[1] M. A. P. W. Ryan Gierke, MD; and Miwako Kobayashi, MD, MPH. "Pinkbook: Pneumococcal disease." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/pneumo.html#streptococcus-pneumoniae (accessed.

[2] C. Troeger et al., "Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory infections in 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016," The Lancet infectious diseases, vol. 18, no. 11, pp. 1191-1210, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www-sciencedirect-com.gate.lib.buffalo.edu/science/article/pii/S1473309918303104.

[3] J. Drijkoningen and G. Rohde, "Pneumococcal infection in adults: burden of disease," Clinical Microbiology and Infection, vol. 20, pp. 45-51, 2014. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1198743X14601750?via%3Dihub.

[4] F. Blasi, M. Mantero, P. Santus, and P. Tarsia, "Understanding the burden of pneumococcal disease in adults," Clinical Microbiology and Infection, vol. 18, pp. 7-14, 2012. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1198743X14613562?via%3Dihub.

[5] "Pneumococcal vaccines WHO position paper - 2012 - recommendations," (in eng), Vaccine, vol. 30, no. 32, pp. 4717-8, Jul 6 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.093.

[6] M. J. Bonten et al., "Polysaccharide conjugate vaccine against pneumococcal pneumonia in adults," (in eng), N Engl J Med, vol. 372, no. 12, pp. 1114-25, Mar 19 2015, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408544.

[7] C. H. van Werkhoven, S. M. Huijts, M. Bolkenbaas, D. E. Grobbee, and M. J. Bonten, "The Impact of Age on the Efficacy of 13-valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in Elderly," (in eng), Clin Infect Dis, vol. 61, no. 12, pp. 1835-8, Dec 15 2015, doi: 10.1093/cid/civ686.