2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(222d) Energy Dissipation Mechanisms in Particle Collisions on Submicron Particle-Layers: Experimental and DEM Analysis

Authors

However, due to the randomness of internal contact network within particle layers and the strong nonlinearity between contact force with contact overlaps, there is no comprehensive theory that fully explains the influence of micro-nano particle layers on the dynamics of particle collision. Further experimental and modeling efforts are required to elucidate these mechanisms. Therefore, we propose to introduce the particle self-assembly method to prepare ordered particle layers as target surfaces. The primary objective is to investigate how layer material and thickness influence both COR and of incident particles. Additionally, based on experimental data, we developed an optimized method for estimating the collision dissipation coefficients of submicron particles.

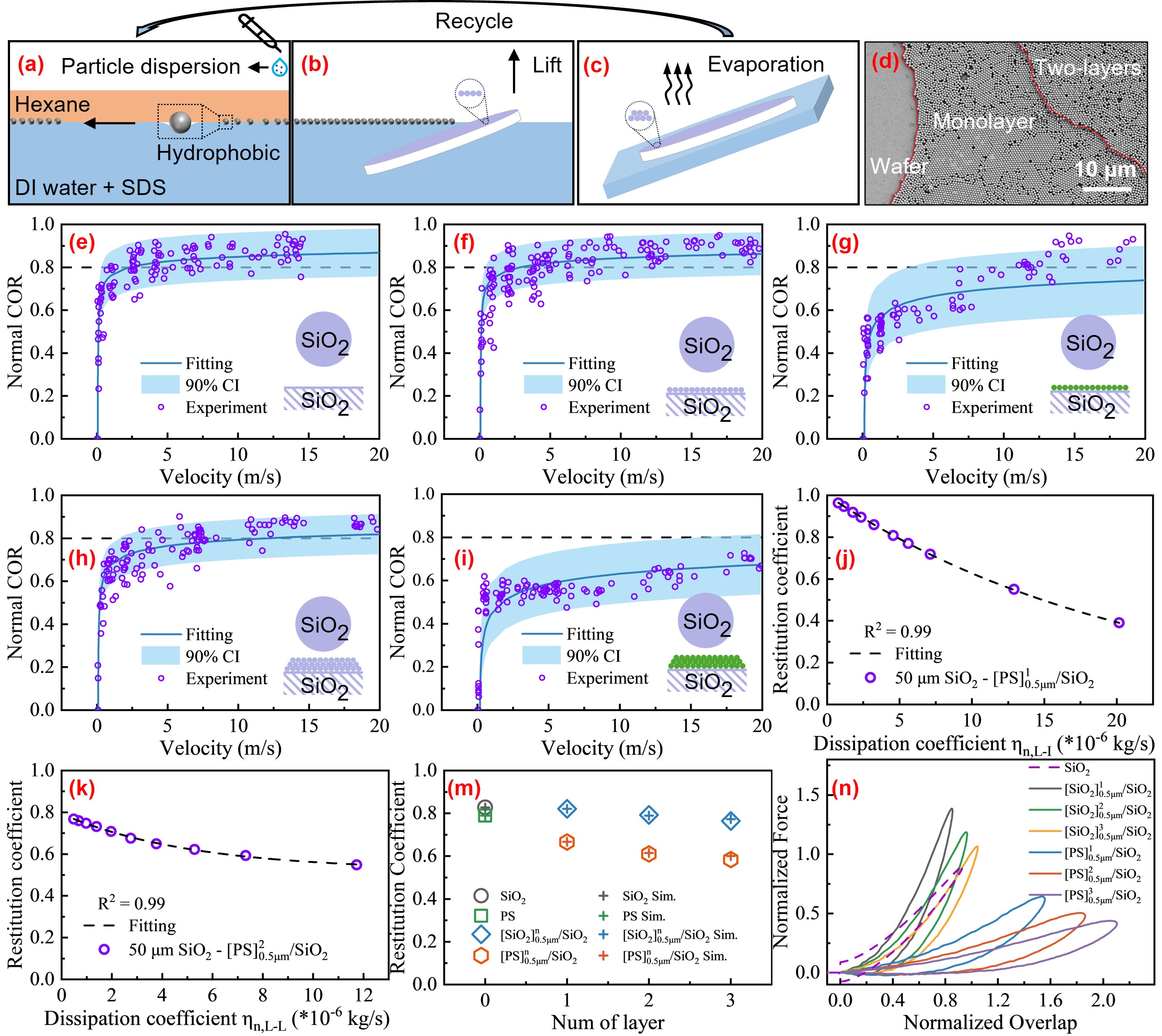

The process for fabricating submicron particle multilayer on wafer involves three primary steps: water-hexane interfacial self-assembly (Fig. 1a), Langmuir-Blodgett transfer (Fig. 1b), and layer-by-layer assembly (Fig. 1c). The morphological changes as the layer-by-layer self-assembly progresses, with the wafer gradually being covered by particles multilayer can be clearly observed in Fig. 1d. Given that the multilayer could be damaged by impact particle, we implemented two precautions. First, the particle impact location was intentionally offset from the target center and second the target rotated by 10 degrees after each capture. These practices can minimize cumulative damage to the layer structure and avoid potential effects from inhomogeneous particle layer. After preparation, the impact experiments will be conducted. Briefly, the system uses nitrogen gas to fluidize and transport the incident particles. The particle velocities are controlled by gas flow. To minimize motion blur, the camera is set to an exposure time of 1 µs. The frame rate is adjusted between 2,000 and 40,000 fps, depending on the incident velocity, allowing for precise tracking particle trajectories.

As depicted in Fig. 1e-i, the trend of COR is similar across all conditions: when the impact velocity is below the capture velocity, the incident particle adheres. As the velocity increases, the COR rises sharply and stable gradually due to viscoelastic dissipation begins to dominate energy dissipation. Besides, a comparison between Fig. 1f and Fig. 1g reveals that the layer material significantly alters the COR, even though the layer diameter is only 500 nm. Further compare with Fig. 1h shows that as the layer thickness increases, the COR requiring higher velocities to reach stabilized.

To quantify the influence, this study combines the JKR theory with dissipative model to analysis the evolution in the force and velocity during the contact process. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the normal dissipation coefficients ηn. For clarity, the incident particle, layer particle and wall surface are denoted as I, L and W, respectively. This results in six dissipation coefficients: ηn,I-I, ηn,I-L, ηn,I-W, ηn,L-I, ηn,L-L and ηn,L-W remain undetermined. In this section, we present a method for determining these coefficients using experimental data from monolayer and bilayer. These coefficients are then validated using experimental data from three layer.

Taking 50μm SiO2-[PS]10.5μm/SiO2 as an example, the subscripts I, L, and W represent 50μm SiO2, 0.5μm PS, and SiO2 wall, respectively. In this experiment, there is only one incident particle. As a result, the ηn,I-I does not influence the calculation. Considering that collisions are mutual, then ηn,I-L=ηn,L-I. Since 50μm SiO2 is 100 times larger than 0.5μm PS, and both the incident particle and wall are made of the same material SiO2, we could assume that the dissipation coefficients for the collision of 0.5μm PS with the 50μm SiO2 and 0.5μm PS with SiO2 wall are similar, which means ηn,L-I≈ηn,L-W. Additionally, from case one, we could obtain ηn,I-W through Fig. 1e. Meanwhile, for the target covered with a monolayer, collisions between the 0.5μm PS particles occur only in the direction perpendicular to the incident velocity. Experimental observations indicate that the surface morphology of the monolayer particle layer remains almost unchanged after impact, with no visible displacement of layer particle. Therefore, it is assumed that collisions between 0.5μm PS particles do not affect the calculation and set ηn,L-L=0. After this analysis above, the only remaining undetermined coefficient in the system is ηn,L-I.

To determine the coefficient ηn,L-I, a suitable range for this coefficient should be decided. The DEM method requires estimating the shortest contact duration before simulation. In this case, the minimal contact duration occurs between the 50μm SiO2 and 0.5μm PS particles contact. The contact duration is calculated through Eq. (1). To ensure a finite contact time, ηn,L-I∈[0,√(5kn,L-ImL-I)).

t=π/√(kn/m-ηn2/(5m2))---(1)

Within this range, we randomly selected ten coefficients ηn,L-I using a logarithmic sampling method. Before each impact simulation, a single pre-simulation is conducted to determine the initial positions of the layer particles. To show the effect of layer thickness on the COR, the incident velocity is set to 5 m/s. Where the particle layer is modeled with a coverage area of 25 × 25 μm for computational efficiency. The incident particle undergoes a central collision with layer particle, with an initial height of 0.1 nm above the layer particle. The effect of contact position is neglected here, and the same setup is used for all subsequent simulations. The COR upon impact with the particle layer are calculated using different ηn,L-I.

COR=e-a*ηn,L-I---(2)

The calculation results are shown in Fig. 1j. It can be observed that the COR follows an exponential relationship with the ηn,L-I, as described by Eq. (2), where a=46644. When ηn,L-I=0, the COR approaches unity. That is because when ηn,L-I≈ηn,L-W=0, the system dissipates energy solely through adhesive forces, resulting in COR close to 1. Combining Eq. (2) with the experimental COR=0.67, the ηn,L-I can be determined to 8.72X10-6kg/s.

Next, we consider the system with 50μm SiO2-[PS]20.5μm/SiO2, where the collisions between 0.5μm PS particles cannot be ignored. Based on the previously determined ηn,I-L=ηn,L-I≈ηn,L-W, the only unknown coefficient in the system is ηn,L-L. Therefore, like the previous step, we perform random sampling within ηn,L-L∈[0,√(5kn,L-LmL-L)) to select ten different ηn,L-L, and calculate the corresponding COR.

The calculation results are shown in Fig. 1k. Referring to the relationship for monolayer case, we observe that the COR also exhibits an exponential decay relationship with the ηn,L-L, as described by Eq. (3), where Cmax=0.79,Cmin=0.52,b=5.15X10-6kg/s. Cmax represents the COR when no dissipation occurs inter 0.5μm PS particle collisions. Combining Eq. (3) with the experimental COR (0.61), the ηn,L-L can be determined to 5.79X10-6kg/s. Similarly, we calculated the variation of COR with the dissipation coefficient for incident particle impact on a SiO2 particle layer.

COR=(Cmax-Cmin)e-ηn,L-L/b+Cmin---(3)

After determining the dissipation coefficients from the monolayer and bilayer, we simulated the incident particle impacts on three-layer target. The comparison between simulation and experiment in Fig. 1m demonstrate that the dissipation coefficients derived from this method can accurately predict COR for three-layer covered target, with a maximum error is less than 3%. This confirms the validity of the proposed approach.

Once the optimized dissipation coefficients were validated, the force-displacement relationship during the incident particles impact on the particle layer can be explored. The overlap and contact force were dimensionless using the Hertzian contact parameters, as shown in Fig. 1n. Notably, for particle layer interactions, the overlap is defined by the downward displacement of the incident particle, rather than the extrusion against the wall. For both layer materials, the results indicate that as the layer thickness increases, the maximum contact force decreases, while both the contact overlap and duration increase. This suggests that thicker particle layers lead to a better buffering effect.

This study combines self-assembly and adhesive DEM simulation to explore how submicron particle layer influences the impact dynamics of incident particle. The results shows that better cushioning effects with thicker layers and softer materials, which leads to higher velocities to reach a stable COR. The dissipation coefficient of submicron particles can be optimized using experimental data from monolayer and bilayer impaction. This approach allows for accurate prediction of impact behavior across different particle layer. Overall, this study presents a novel method for understanding micro and nano particle layers' influence on incident particle dynamics, with implications for fine particle transport, deposition control, and aggregation modeling in both industrial and environmental applications.