2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(601d) Enabling Workflow Development for Bristling Shark Denticle with Fluid-Structure Interaction

To accurately model the denticle movement and deformation, the researchers implemented strong two-way Fluid-Structure Interaction (FSI), in which the fluid and structural solvers are coupled so that the flow pressure can bend the denticle and the bristling action can affect the flow field. Because the denticle structure is moving and deforming at scales that are much larger than computational cell sizes, the conformal method involves updating the CFD mesh to accommodate the motion of the interface. Accomplishing this in 3D is tedious and often involves computationally expensive remeshing, invalid mesh elements, poor-quality mesh elements, irregular cut-cell transitions near the interface, or complex overset methods. It is for this reason that many researchers utilize non-conformal methods that do not require dynamic meshes. However, these methods cannot provide a well-structured grid in the boundary layer of the moving interface. Therefore, it was necessary to develop a novel “dual-scale” conformal mesh update method.

A proof-of-concept model that utilized a custom combination of two dynamic mesh methods to update the grid surrounding a simplified denticle geometry was created. Dynamic Layering and several sliding mesh interfaces absorbed the large-scale oscillations of the denticle, while Smoothing captured the small-scale deformation of the fluid-solid interface. Dynamic Layering can be used in conjunction with sliding mesh interfaces to absorb large boundary displacements in prismatic cell regions (ex. Piston). However, it is unable to accommodate deforming boundaries. Smoothing, on the other hand, can adeptly absorb the motion from deforming boundaries, but it is unable to handle large boundary displacement. Combining these two mesh update methods enabled the creation of a mesh that only contained hexahedral elements and could absorb large boundary displacement while maintaining mesh quality and resolution near the denticle surface.

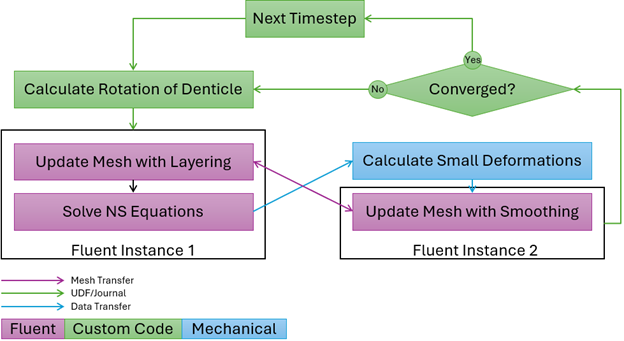

To avoid writing new code, the dynamic mesh update methods and FSI capabilities built into ANSYS Fluent were used for this simulation. However, the ANSYS Fluent/Mechanical coupling does not work with Dynamic Layering. Because of the dual-scale nature of the mesh update coupling, it cannot be done natively within Fluent. Therefore, it was necessary to use User Defined Functions and journal files to couple two instances of Fluent together. The first instance solved the governing equations and utilized Dynamic Layering to absorb the large-scale rotational mode of denticle motion, while the second instance leveraged the Workbench one-way coupling with ANSYS Mechanical to solve for the small-scale bending and twisting of the denticle.

The dual-scale mesh update mesh method accommodated the deformations and rotation of the denticle while maintaining excellent quality hexahedral cells near its surface. The denticle successfully mimicked the behavior of real shark scales by flapping up into the flow in response to adverse pressure gradients. However, further validation is needed to confirm the accuracy of the drag and deformation calculations.