2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(341d) Elongational Stress Dominated Flow Fields Impart Higher Degrees of Cellular Damage Than Shear Stress Dominated Flow

Authors

With the increasing use of blood contacting medical devices, such as mechanical circulatory support (MCS) and prosthetic heart valves, as well as the increased use of bioreactors for biopharmaceutical engineering, it is important to fully understand the effect of imposed fluid stresses on cells. Cells exposed to high, non-physiologic, fluid stresses are likely to experience some level of damage, ranging from severe where cells are completely destroyed (i.e. lethal damage), to less severe where cells survive with impaired function (i.e. sublethal damage). The effect of fluid stresses on cells has been a topic of study for quite some time but often focusing solely on the effects of shear stress which tends to be understood as the main source of cell deformation/damage. Often extensional stresses are neglected and their effect thought to be negligible due to their small magnitude and prevalence in devices compared to shear, but recent studies measuring the extent of deformation indicate that extensional stresses might be more damaging to cells (higher deformation indexes) than shear stresses of equal magnitude. This is in agreement with the fundamental work on emulsion formation by GI Taylor, where he showed that liquid droplets deform to similar shapes under both extensional and shear flows, but only the extensional flows causes the liquid droplet to burst. As such, it is essential to understand the effects of both shear and extensional stress to improve blood contacting medical devices as well as bioreactor environments, via reduction of cellular damage. We sought to probe the effects of extensional and shear stress on cellular damage using red blood cells (RBCs), which are often used as a model to understand biologic membranes. Specifically, we hypothesize that extensional stresses will inflict higher levels of mechanical trauma to RBCs than shear stress.

Methods:

To probe the effects of extensional and shear stress, isolated porcine RBCs, from abattoir blood, at 37% packed cell volume were perfused through a mock circulation loop (180 mL) using an MCS device (CentriMag Pump) at 1.5 L/min for 5 hours. Experimental loops contained either a sharp (3:1) or gradual contraction of the flow field, which inflicted extensional or shear stress dominated environments, respectively. The set-up was inspired by the FDA Critical Path Initiative nozzle which utilizes similar contractions, and was designed to emulate stresses in MCS. Each experimental day, two loops were run in an alternating order, one with a flow contraction (sharp or gradual) and one with no contraction as a control. A total of 5 experiments were performed for each contraction type (one outlier removed for the gradual runs) and 10 experiments for the control loop. Additionally, a 50 mL aliquot of RBCs was used as a stagnant control for each loop to account for production of RBC damage markers due to aging (n=20). For each loop and stagnant control, samples were collected from bulk RBCs (t=-1hr), the start of perfusion, and after every hour. RBC damage was monitored by measuring two markers, hemolysis (i.e. the release of hemoglobin due to RBC lysis), a marker of lethal cell damage, and the release of extracellular vesicles (EVs) from the RBC membrane, a marker of sublethal damage. Traditionally, hemolysis is used to measure RBC damage, specifically in the field of MCS pump testing and design. Even so, it is well understood that other markers of damage need to be evaluated and studied to obtain a more complete picture of the trauma inflicted to RBCs. As such we chose to monitor both hemolysis and EV generation as a marker of sublethal damage, to give a more complete picture of the extent of damage being inflicted.

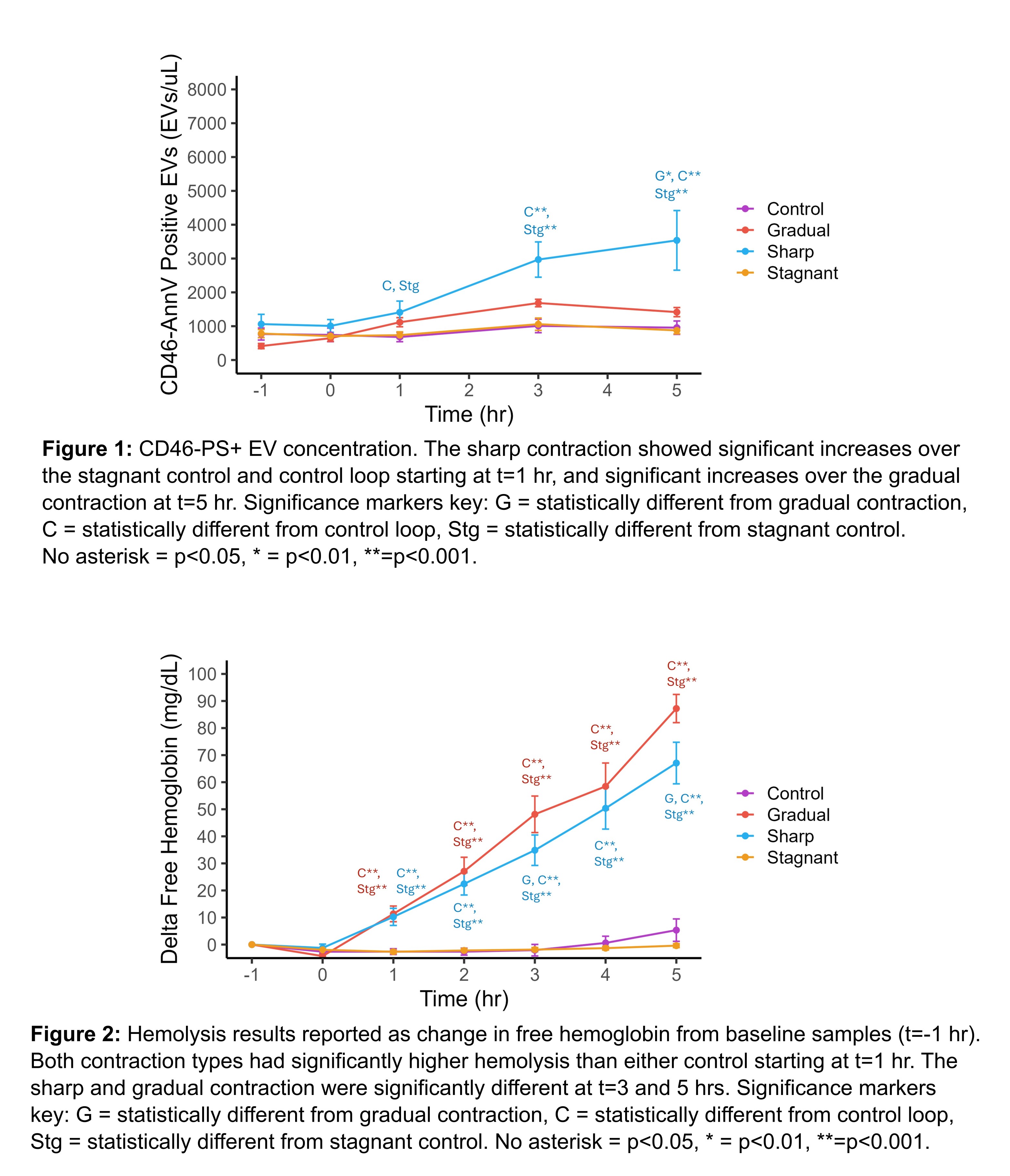

We chose EVs as an additional marker as they are clinically relevant in MCS patients. Recent studies indicate that elevated levels of EVs in MCS patients could be contributing to the development of common adverse events (bleeding and thrombosis), which are often thought to be caused by poor hemocompatibility due to elevated fluid stresses. Secondly, EVs often have externalized phosphatidylserine (PS), one of the phospholipids typically found on the inner cell membrane, which is procoagulant and can initiate and propagate the coagulation cascade. As MCS patients often experience clotting as an adverse event, these procoagulant EVs are of interest. Flow cytometry was used to monitor EV levels with perfusion time. Specifically, EVs were tagged with anti-porcine CD46-AlexaFluor 488, which labels RBCs and annexin V-AlexaFluor 647, which labels PS. EVs were analyzed for concomitant signal (CD46-PS+) over the size range 0.5-1 μm. Additionally, hemolysis was measured by the Harboe assay. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA at each time point with Tukey’s HSD post-hoc testing, with all data reported as mean ± standard error. Significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results:

The concentration of CD46-PS+ EVs increased from 1,062±288 EV/μL at baseline to 3,537±881 EV/μL at t=5 hours for the sharp contraction and from 413±77 to 1,416±136 EV/μL for the gradual contraction, while the concentration remained constant for both controls (Figure 1). The sharp contraction was greater than the controls starting at t=1 hr (p<0.05) and consistently higher than the gradual contraction, becoming significant at t=5 hr (p<0.01). Trends observed for hemolysis with the sharp and gradual contractions were similar having a change in free hemoglobin at t=5 hr from baseline of 67.1±7.7 and 87.2±5.2 mg/dL respectively, with both controls showing no to minimal hemolysis (Figure 2). Both the sharp and gradual contractions were significantly different from controls starting at t=1 hr (p<0.001) and significantly different from each other at t=3 and t=5 hr only (p<0.05). The normalized index of hemolysis was 0.017±0.002, 0.023±0.001, and 0.002±0.001 g/100L for the sharp, gradual, and control respectively, with the sharp and gradual contraction significantly different from only the control (p<0.001).

Discussion and Conclusions:

While both EV concentration and hemolysis increased for both the sharp and gradual contraction, the difference in hemolysis is minimal between contraction type. In contrast, the sharp contraction produced significantly more EVs compared to the gradual contraction. This observation shows that extensional stresses were more damaging to RBCs than shear stresses when it comes to EV production, although there was no difference for hemolysis at this particular flow condition. Treating RBCs as a model for biologic membranes, this work suggests that monitoring sublethal damage, specifically EV production, may be a more sensitive marker of cellular damage indicating issues with medical devices and/or bioreactors prior to significant levels of lethal damage. For direct application of RBC damage, for example in MCS device development, EV production from RBCs might be a better, more sensitive measure of RBC damage than the traditional marker, hemolysis, with improved capability to assess device performance. More work is needed at a variety of flow rates to access the differences in cellular damage inflicted by either extensional or shear stresses, but this preliminary study using RBCs as a model for cells in general, seems to indicate that extensional stresses are in fact more damaging especially when sublethal damage markers are monitored.