2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(269b) Efficient Regeneration of CO2 Capture Solution Using Bipolar Membrane Electrodialysis

Attempts to cut down current greenhouse gas emissions often fail to address hard-to-abate and decentralized CO2 emissions. To offset these emissions, society needs to improve the energy efficiency of CO2-negative technologies such as direct air capture (DAC). We utilize bipolar membrane electrodialysis (BPMED) to generate an alkaline solution to perform CO2 absorption from air and regenerate the alkaline capture solution to release concentrated CO2. BPMED can be fully electrified and integrated with renewable electricity which offers a main advantage over more traditional DAC approaches reliant on temperature swings.

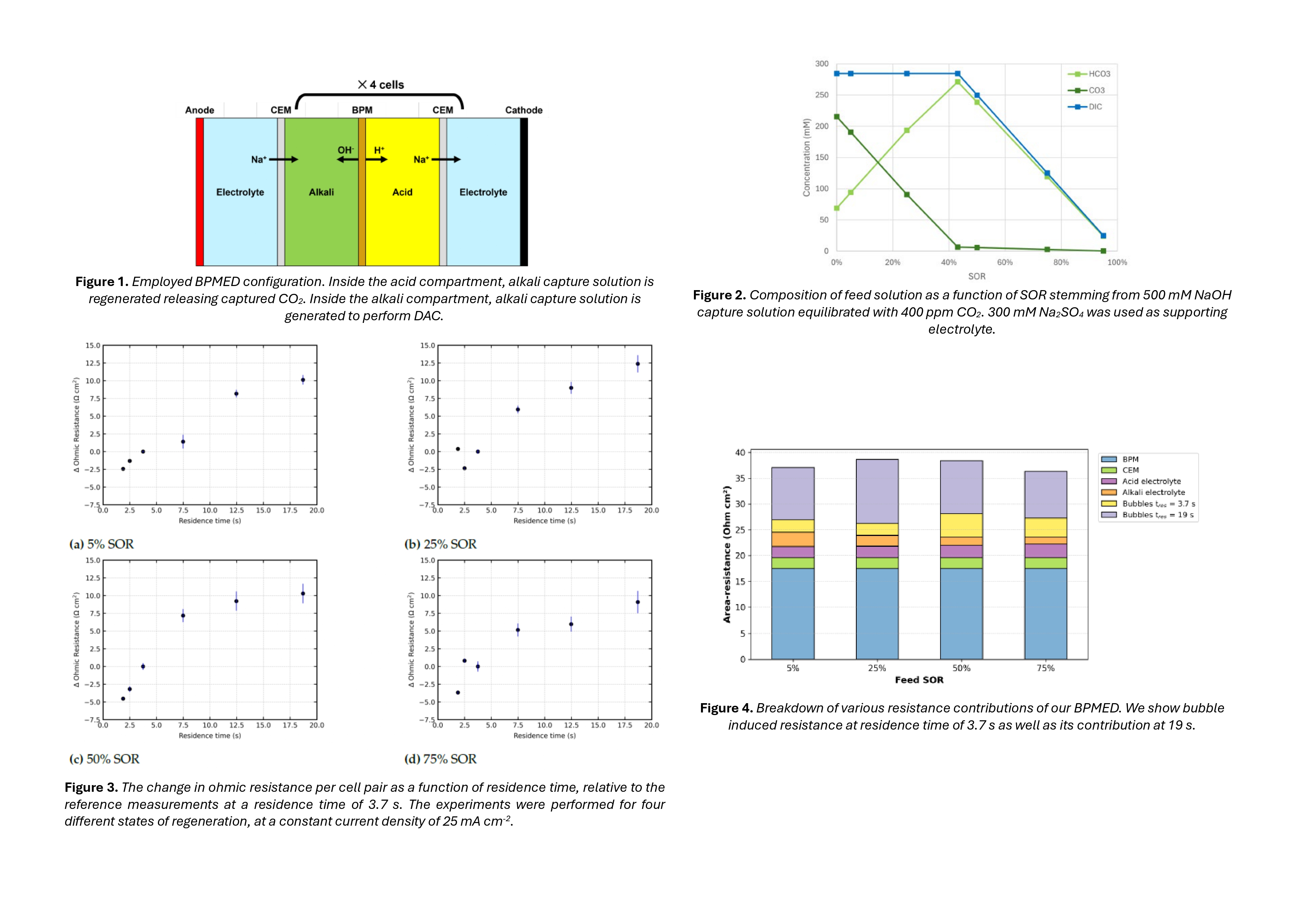

Regeneration of capture solution by BPMED is based on pH swing. When applying voltage over the membrane stack, bipolar membranes (BPMs) facilitate water dissociation at their catalyst interface. To close the ion circuit additional membranes must be used. Figure 1 shows the specific configuration used in this work.

Notably, CO2 gas evolution inside the BPMED stack prevents this technology from reaching lower energy consumption. CO2 gas bubbles block part of the active area inside the BPMED stack, leading to locally intensified current densities and a higher voltage loss. To reduce the impact of gas bubbles, research mostly considers high-pressure operation that postpones CO2 oversaturation and reduces gas bubble size leading to increased available active area. However, this approach calls for high-pressure durable equipment, and even at around 26 bar the bubble-induced resistance can comprise around 50% of total cell resistance.

Additionally, modeling work often strictly couples CO2 absorption with CO2 regeneration. This binds the BPMED to a single-pass operation and couples liquid residence time to the applied current density. This approach does not leave enough freedom for BPMED optimization.

Here, we offer a new approach by decoupling the CO2 absorption from CO2 regeneration by shifting to a semi-batch process. This allows us to independently optimize liquid residence time and current density and define a state-of-regeneration (SOR, analog to state-of-charge). 0% SOR solution thus indicates a 400 ppm CO2 saturated solution while 100% SOR solution indicates a fully regenerated solution free of absorbed CO2. At low SOR, the acidification converts CO32- to HCO3- and we could hypothetically avoid CO2 gas evolution. At high SOR, the acidification converts HCO3- to CO2 where we could reduce the impact of gas bubbles by tuning the liquid residence time.

Methods

The effect of CO2 bubbles is investigated in a lab-scale BPMED stack (4 BPMs each with 100 cm2 operated at 25 mA cm-2 and liquid compartment thickness 425 µm) at 5, 25, 50, and 75% SOR solutions (Figure 2) and various liquid residence times (1.9 to 19 s). Separate measurements and computational estimates are employed to quantify the ohmic resistance of cation-exchange and bipolar membranes, liquid solutions, and cathode/anode. The current-interrupt method is applied over the BPMED stack to measure the overall stack resistance. The ohmic resistance contribution of CO2 gas bubbles is found by measuring standard deviation in ohmic resistance, relative changes in ohmic resistance, and by combining all individual contributions to the overall ohmic resistance.

Results

Standard deviation in ohmic resistance can be qualitatively linked to the intensity of CO2 gas evolution and can highlight a transition point for which bubble formation is largely prevented. 5% SOR solutions can prevent bubble formation below 5 s residence time while 25% SOR can prevent bubble formation below 2.5 s residence time. At higher SORs bubble formation was never prevented. Maximum deviations in ohmic resistance also always increase with increasing SOR which is in line with expectations.

However, with increasing residence time, the ohmic resistance always linearly increases. The trend and magnitude of this change are the same for all SOR solutions tested (Figure 3). While expected for high SOR solutions where gas evolution is always present, this is contrary to our initial expectation that the low SOR solutions will induce fewer gas bubbles and will thus see less of an improvement in ohmic resistance. It is also contrary to visual observations and deviations in ohmic resistance where 5 and 25% SOR solutions show no, or little gas evolution compared to 50 and 75% SOR solutions.

Based on the above contradiction we propose two different mechanisms. First, the supersaturation of CO2 leads to the formation of dynamic bubbles which move through the liquid compartment and exit through the outlet manifold. These dynamic bubbles temporarily block part of the electrolyte and membrane and give rise to strong deviation in ohmic resistance. Second, we suspect that the acidified part of the bipolar membrane gives rise to a baseline of static bubbles adhering to the surrounding membranes and spacer. The static layer of bubbles does not give rise to strong deviations in ohmic resistance but still results in decreasing ohmic resistance with decreasing residence time as the adhesive forces are overcome by the drag force exerted by the liquid flow.

Further, we show that CO2 gas bubbles contribute to an increase in resistance in two ways. First, as commonly described in the literature, these bubbles reduce the overall liquid conductivity. Second, the static bubbles mask part of the membrane surface, which decreases the available membrane area. We deduce, from our resistance measurements and estimated gas fractions, that the latter effect is dominant.

Finally, we can also quantify the absolute value of CO2 bubble ohmic resistance. Figure 4 shows that at high residence times (19 s) CO2 gas bubbles may take up to 40% of total cell ohmic resistance. This can be significantly improved when moving to residence time of 3.7 s where CO2 gas bubbles still take up around 10% of the total ohmic resistance.

Implications

Our work shows that bubble-induced resistance can take up to 40% of the total cell resistance and that this can be effectively decreased to 10% by moving to lower residence times. However, upon moving to industrial scales, the upscaling in both current density (from 25 mA cm-2 to ~ 100 mA cm-2) and the size of the active area (100 cm2 to ~2500 cm2) is expected to further enhance the negative effect of bubble induced resistance. Future work should further explore the two proposed bubble mechanisms and strategies that can effectively address this bubble-induced resistance.