2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(348f) The Effect of Plastic Feedstock Composition on Heteroatom Formation in Pyrolysis Oil

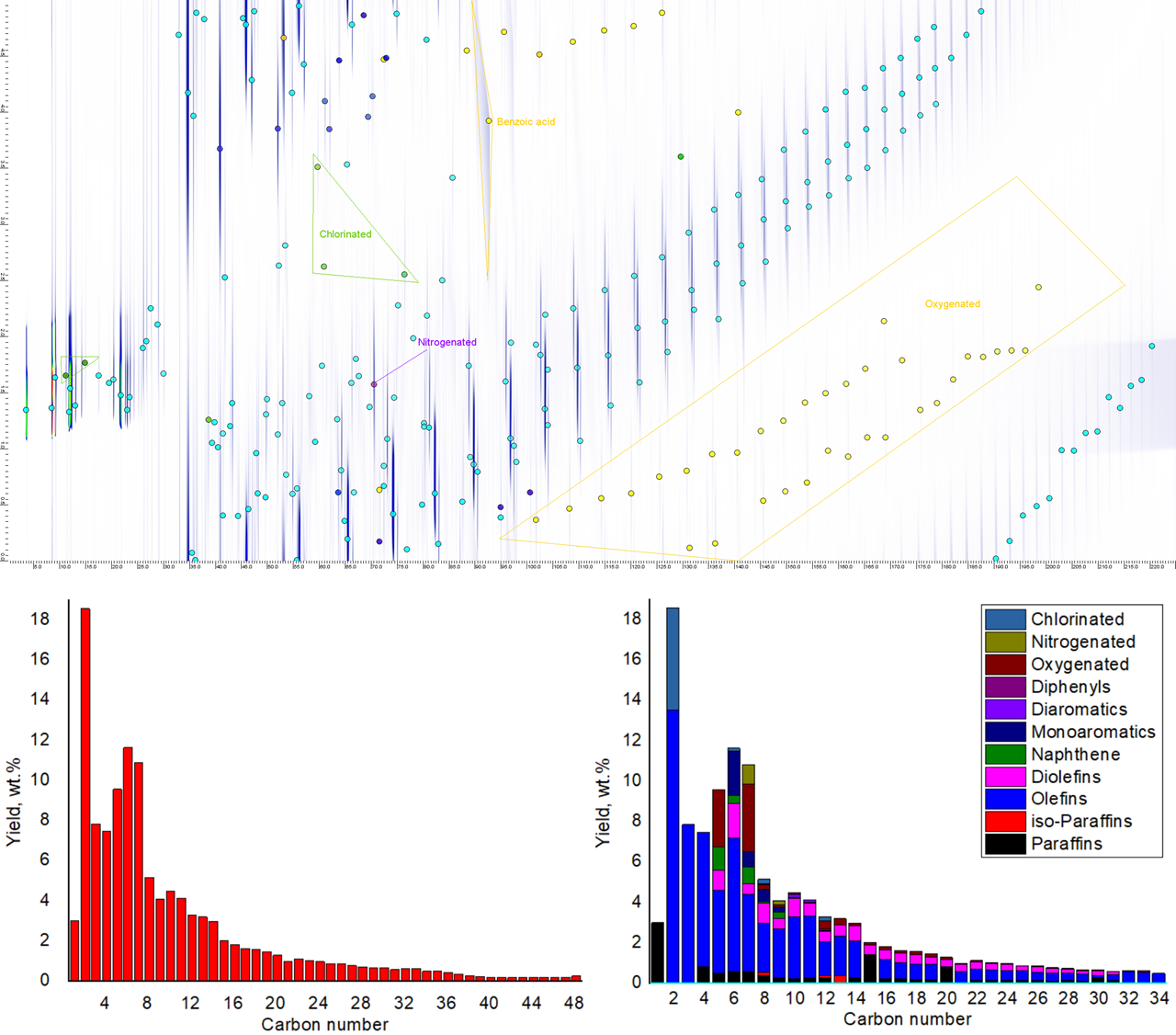

Pyrolysis experiments were conducted at 600 °C with a carrier gas flow rate of 20 mL/min using a double-shot tandem micro-pyrolysis system coupled with comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography (GC×GC-FID/ToF-MS). Polyethylene (PE) was first pyrolyzed individually, followed by systematic additions of polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and Nylon 6,6 to form a representative plastic mixture (65% PE, 10% PVC, 10% PET, 15% Nylon 6,6). The powdered plastics (0.1–0.3 mm) underwent pyrolysis for 5 minutes, with volatile products trapped at -170 °C and analyzed via GC×GC. Chromatographic separation was achieved based on boiling point (1D) and polarity (2D).

The inclusion of heteroatom-containing plastics resulted in the formation of chlorinated, oxygenated, and nitrogenated species in the pyrolysis oil, with a carbon number distribution ranging from C2 to C48. The resulting chromatograms revealed complex mixtures of aromatics, naphthenes, (iso-)olefins, (iso-)paraffins, chlorinates, oxygenates, and nitrogenates with detailed heteroatom characterization visualized via GC Image analysis. Mass spectrometry (ToF-MS) and flame ionization detection (FID) enabled compound identification and quantification using the molar response factor (MRF) method10. While chlorinated hydrocarbons were formed in the 10% PVC addition, light olefin production decreased. Subsequently, oxygenated hydrocarbons appeared in the pyrolysis oil by adding 10% PET to the feedstock, and aromatic (benzene, toluene, xylene) production changed remarkably. 15% Nylon6,6 was included in the plastic mixture to observe nitrogenated compounds. Final mixture produced 7.22 wt.% oxygenates, 1.17% wt.% nitrogenates, and 3.01 wt.% chlorinates. Understanding the extent of heteroatom contamination in pyrolysis oil derived from mixed plastic waste is crucial for optimizing recycling strategies. This study provides key insights into the transfer of contaminants during pyrolysis, informing approaches for further processing to minimize reliance on fossil feedstocks. Our findings demonstrate that plastic-derived oil presents a viable and sustainable alternative for fossil naphtha, while contributing to the circular economy and reducing carbon footprint.

References

- M. Kusenberg, A. Eschenbacher, L. Delva, S. De Meester, E. Delikonstantis, G. D. Stefanidis, K. Ragaert and K. M. Van Geem, Fuel Processing Technology, 2022, 238.

- M. M. Hasan, R. Haque, M. I. Jahirul and M. G. Rasul, Energy Conversion and Management, 2025, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2025.119511, 1-25.

- M. I. Jahirul, M. G. Rasul, D. Schaller, M. M. K. Khan, M. M. Hasan and M. A. Hazrat, Energy Conversion and Management, 2022, 258.

- Y. W. Y. Peng, L. Ke, L. Dai, Q. Wu, K. Cobb, Y. Zeng, R. Zou, Y. Liu, R. Ruan, Energy Conversion and Management, 2022, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2022.115243, 1-16.

- S. H. Chang, Science of the Total Environment, 2023, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162719, 1-24.

- S. Ügdüler, K. M. V. Geem, M. Roosen, E. I. P. Delbeke and S. D. Meester, Waste Management, 2020, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2020.01.003, 148-182.

- M. Kusenberg, A. Eschenbacher, M. R. Djokic, A. Zayoud, K. Ragaert, S. De Meester and K. M. Van Geem, Waste Manag, 2022, 138, 83-115.

- D. Munir, M. F. Irfan and M. R. Usman, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2018, 90, 490-515.

- G. Martínez-Narro, S. Hassan and A. N. Phan, Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2024, 12.

- S. L. Jean-Yves de Saint Laumer, Emeline Tissot, Lucie Baroux, David M. Kampf, Philippe Merle, Alain Boschung, Markus Seyfried, Alain Chaintreau, Journal of Separation Science, 2015, 38, 3209-3217.