2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(237f) Economic and Environmental Assessment of the US Organic Waste from Hydrothermal Waste Valorization Pathways

Introduction

The United States consistently generates nearly 200 million tons of organic waste annually from municipal, agricultural, and industrial sources1,2. Organic wastes rich in carbohydrates, proteins, and lignin have historically been managed through landfilling, composting, or incineration, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions and resource inefficiency3. Emerging waste valorization technologies, particularly HTL, offer a promising alternative by converting wet, heterogeneous organic waste into biocrude oil and other co-products that can be upgraded into fuels, fertilizers, and materials4. However, the viability of HTL depends heavily on feedstock characteristics, conversion efficiency, downstream upgrading options, and policy context.

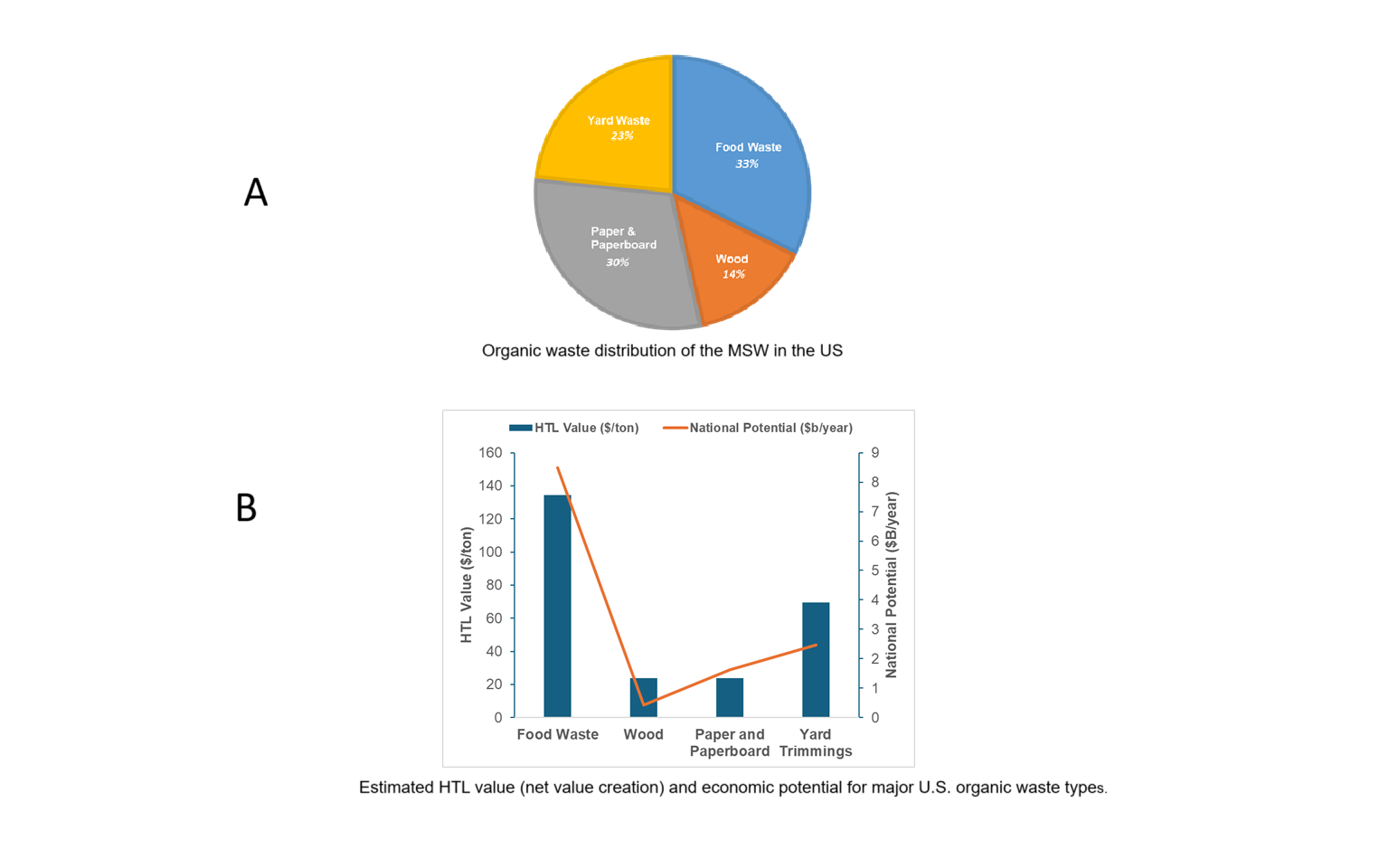

This study assesses the economic and environmental potential of HTL applied to the organic fraction of MSW as defined by the US EPA2, that broadly includes food waste, yard trimmings, wood, and paper as depicted in Figure 1. The analysis is structured around three decision cases designed to guide technology deployment and policy design:

Case 1: Evaluate the internal rate of return (IRR) for different HTL upgrading pathways—including baseline crude, refined fuels, and construction products like biobinder for asphalt production—to identify the most economically viable end-use configurations. This consists of a sensitivity check for when upgrading adds cost without sufficient revenue uplift.

Case 2: Estimate the economic value of various MSW feedstocks in terms of $/ton based on their biochemical composition and conversion efficiency through HTL, providing a feedstock-centric view of waste valuation potential.

Case 3: Benchmark HTL against conventional waste management alternatives including landfilling, anaerobic digestion (AD), composting, and combustion/waste-to-energy (WTE) regarding IRR and carbon intensity. This comparison is used to identify where HTL has comparative advantages and where targeted policy support (e.g., carbon credits, infrastructure investment, technology-specific subsidies) could enable wider adoption.

Together, these cases offer a comprehensive framework to inform HTL deployment strategies and support integrating this technology into a circular, decarbonized U.S. waste management system.

Processes & Products

This study centers on HTL as a primary waste-to-value pathway for the organic fraction of U.S. MSW, with comparative benchmarking against existing waste management technologies such as AD, composting, combustion/WTE, and landfilling. HTL is particularly suited for wet, heterogeneous feedstocks, converting them into biocrude oil and co-products like biochar, nutrient-rich aqueous streams, and gases. These outputs can be further upgraded into renewable diesel, jet fuel, asphalt binders, or fertilizers depending on market demand and infrastructure. However, HTL facilities are capital-intensive and require a steady, sizable volume of compatible feedstock. This makes them more feasible near wastewater treatment plants or in urban hubs with centralized waste collection.

In Case 1, we evaluate the economic viability of different HTL end-use configurations by estimating the IRR under multiple upgrading scenarios using open-source python-based module developed using BioSTEAM5 and QSDsan6. Base-case biocrude yields IRRs of 15% and competes well with Crude Tall Oil (CTO)7, while downstream upgrading to renewable fuels or specialty products can push IRRs above 22%, provided the value of the upgraded product outweighs added processing and capital costs. However, in cases where upgrading does not enhance economic value—either due to market saturation or high cost of upgrading infrastructure—the base biocrude pathway remains the most viable option.

For benchmarking, , as an alternative technology, is used for tentatively 15-20% of the food waste8 and a small amount of biosolids from WRRFs9, converting organics to biogas and digestate. Typical IRRs for AD systems range from 9–13%, influenced by tipping fees, energy credits, and digestate utilization10. Composting remains a preferred option for yard waste and woody biomass with IRRs of 3–7%, though its main value lies in environmental benefits such as methane avoidance and soil health improvement11. Combustion or WTE facilities process mixed or low-moisture waste streams to produce electricity and heat. However, their IRRs are often <5% without significant subsidies or high energy prices. Landfilling, while common, generates minimal economic return and contributes heavily to methane emissions, positioning it as the least desirable economic and environmental option. Composting and combustion represent low-tech and often low-return options, typically reserved for yard trimmings or heterogeneous low-moisture wastes. Composting yields IRRs of around 3–7%, making it a marginally profitable pathway that is more often justified by its environmental co-benefits, such as soil health improvement and methane avoidance. Combustion of organic waste for electricity or heat, while technically feasible, shows IRRs below 5% under current energy pricing. This pathway is generally only viable in regions with high landfill tipping fees or strong energy incentives. These IRRs and comparisons of carbon intensities underscore the importance of matching specific waste types to suitable technologies to maximize financial returns while considering environmental outcomes.

Baseline Scenario

To establish a baseline valuation for HTL applied to the organic fraction of U.S. MSW, this study modeled the biochemical composition of four major waste categories—food waste, yard trimmings, wood, and paper—and estimated their potential economic value when processed via HTL. We calculated the economic value in $/ton of waste based solely on HTL outputs using feedstock-specific conversion efficiencies, product yields, and market prices. This feedstock-centric valuation reflects how the biochemical makeup—especially lipid, protein, cellulose, and ash content—influences both biocrude yield and co-product potential.

Results show that food waste holds the highest net economic value creation through HTL, estimated at $20–140/ton, due to its high moisture content and favorable biochemical profile (rich in lipids and proteins). Wood and paper, while abundant, yield lower HTL returns ($30–60/ton) due to their high lignocellulosic content and lower conversion efficiency to biocrude. Yard trimmings fall in a similar range ($25–50/ton), with variability depending on leaf-to-wood ratio and moisture. On a national scale, if HTL were deployed at sufficient capacity to valorize these streams, the total potential economic value of organic MSW via HTL is estimated at $10–15 billion annually. This figure reflects product-equivalent market prices for HTL-derived fuels, fertilizers, and biochar.

However, current infrastructure limitations, high capital costs, and the lack of integrated feedstock collection systems leads to high costs and emissions. Food waste currently is largely landfilled, while yard and wood waste are frequently mulched, , or composted with or without energy recovery. Bridging this gap will require regional aggregation of feedstocks, modular HTL deployment at scale, and the development of supportive policies to make HTL cost-competitive for a broader range of waste types.

Policy Implications

Baseline technologies such as and composting benefit from well-established incentive structures, including renewable energy credits, tipping fees, and compost procurement mandates12. These subsidies allow them to remain financially viable despite relatively low product revenue. In contrast, HTL—despite offering high returns and strong environmental performance for select feedstocks—is often hindered by high upfront capital costs, limited infrastructure, and lengthy permitting timelines. As a result, HTL adoption remains limited, especially for waste types like food, paper, or yard trimmings, where other technologies already enjoy policy support.

Targeted policies are essential to unlock HTL’s broader potential, particularly for producing low-carbon fuels and co-products such as sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) or biobinders. Investment tax credits, modeled after the Clean Hydrogen Production Tax Credit (Section 45V) established by the Inflation Reduction Act, could improve HTL project IRRs by 3–5 percentage points. Including HTL-derived fuels under the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) or Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) would further monetize its carbon reduction benefits by 50%. Streamlined permitting, low-interest green loans, and feedstock-specific tipping fee incentives could help overcome economic barriers and scale deployment. These actions would help states and municipal authorities reduce waste going to landfills, better use organic waste, and earn more revenue from waste processing.

References

(1) Langholtz, M. H. 2023 Billion‐Ton Report: An Assessment of U.S. Renewable Carbon Resources; ORNL/SPR-2024/3103; Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN. doi: 10.23720/BT2023/2316165.

(2) Advancing Sustainable Materials Management: 2018 Fact Sheet; US EPA.

(3) Downstream Management of Organic Waste in the United States: Strategies for Methane Mitigation; United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2022.

(4) Feng, J.; Li, Y.; Strathmann, T. J.; Guest, J. S. Characterizing the Opportunity Space for Sustainable Hydrothermal Valorization of Wet Organic Wastes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58 (5), 2528–2541. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c07394.

(5) Cortes-Peña, Y.; Kumar, D.; Singh, V.; Guest, J. S. BioSTEAM: A Fast and Flexible Platform for the Design, Simulation, and Techno-Economic Analysis of Biorefineries under Uncertainty. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8 (8), 3302–3310. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b07040.

(6) Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Morgan, V. L.; Lohman, H. A. C.; Rowles, L. S.; Mittal, S.; Kogler, A.; Cusick, R. D.; Tarpeh, W. A.; Guest, J. S. QSDsan: An Integrated Platform for Quantitative Sustainable Design of Sanitation and Resource Recovery Systems. Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol. 2022, 8 (10), 2289–2303. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2EW00455K.

(7) Churchill, J. G. B.; Borugadda, V. B.; Dalai, A. K. A Review on the Production and Application of Tall Oil with a Focus on Sustainable Fuels. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 191, 114098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.114098.

(8) Schroeder, J. Anaerobic Digestion Facilities Processing Food Waste in the United States; Survey Results EPA 530-R-23-003; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): Washington, DC, 2023.

(9) Vutai, V.; Ma, X. C.; Lu, M. The Role of Anaerobic Digestion in Wastewater Management. EM (Pittsburgh Pa) 2016, 0 (September 2016), 12–16.

(10) Smith, S. J.; Satchwell, A. J.; Kirchstetter, T. W.; Scown, C. D. The Implications of Facility Design and Enabling Policies on the Economics of Dry Anaerobic Digestion. Waste Management 2021, 128, 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2021.04.048.

(11) Unleashing the Economic and Environmental Potential for Food Waste Composting in the U.S.; Closed Loop Partners. https://www.closedlooppartners.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/FINAL-CLP… (accessed 2025-04-04).

(12) Commission, C. E. Enabling Anaerobic Digestion Deployment to Convert Municipal Solid Waste to Energy. https://www.energy.ca.gov/publications/2020/enabling-anaerobic-digestio… (accessed 2025-04-04).