2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(390af) Economic and Environmental Assessment of Hydrogen Refueling Stations: A Comparative Study of Energy Storage Strategies

The increasing integration of renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind, into power grids has further elevated the importance of hydrogen as an energy storage medium to balance supply and demand fluctuations (Boretti & Castelletto, 2024). Additionally, hydrogen serves as a feedstock for industrial applications, including ammonia and methanol production, further reinforcing its role in decarbonization efforts (IEA, 2024). However, despite its potential, the deployment of hydrogen infrastructure remains constrained by high costs, energy losses during conversion, and the need for efficient storage and distribution systems (Wang et al., 2025). Variability in hydrogen production costs due to fluctuating electricity prices and capital expenditures presents additional challenges for widespread adoption (Nnabuife et al., 2023).

This study conducts a comprehensive techno-economic (TEA) and life cycle assessment (LCA) of two energy storage strategies—Battery Energy Storage System (BESS, Case 1) and Hydrogen Storage System (HSS, Case 2)—designed to support a 1,000 kg/day alkaline water electrolysis (AWE)-based hydrogen refueling station. By systematically analyzing cost structures, environmental impacts, and regional variations, this work quantifies the feasibility of different energy storage approaches under real-world operational constraints.

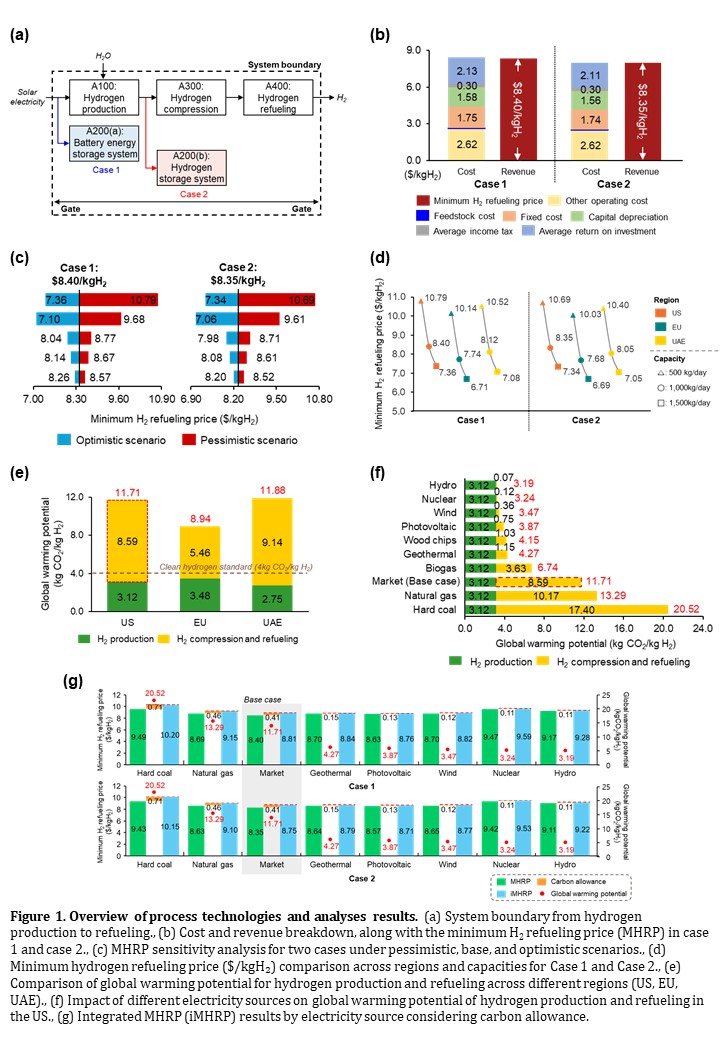

This study compares two energy storage strategies designed to support a 1,000 kg/day AWE-based hydrogen refueling station: Case 1, which employs a BESS to buffer intermittent solar electricity, and Case 2, which utilizes an HSS to store excess hydrogen produced during periods of surplus power. The integration of these storage strategies has significant implications for the economic and environmental sustainability of hydrogen refueling infrastructure, affecting not only capital and operational costs but also overall system efficiency. The system boundary spans from hydrogen production via AWE to hydrogen compression and dispensing. Figure 1(a) illustrates the detailed process flow, highlighting key subsystems such as electricity storage (A200a) in Case 1 and hydrogen storage (A200b) in Case 2.

To assess the economic and environmental feasibility of the two energy storage strategies, this study employs a combined TEA and LCA framework. The TEA was conducted using equipment cost data provided by Korea Gas Technology Corporation and literature-based operational cost estimates, incorporating equipment-specific capital and operating costs across storage, compression, and dispensing subsystems. The minimum hydrogen refueling price (MHRP) was calculated using a discounted cash flow (DCF) method, with assumptions based on a 20-year plant life, 90% capacity factor, and region-specific electricity costs. Key input parameters were varied in a sensitivity analysis to identify critical economic drivers, including discount rate, electricity price, and refueling capacity. Additionally, variations in tax rates and fixed capital investment costs were analyzed to assess their impact on financial feasibility. Sensitivity analysis also examined policy-driven factors such as carbon pricing and renewable energy subsidies to evaluate their influence on the long-term cost competitiveness of hydrogen refueling stations.

For the environmental analysis, an attributional LCA was performed using the ReCiPe 2016 midpoint method, with a system boundary covering hydrogen production, compression, storage, and dispensing. The primary environmental indicator considered is Global Warming Potential (GWP, kgCO₂-eq/kgH₂), supplemented by other impact categories such as fossil resource depletion and freshwater consumption. The LCA modeling was implemented in SimaPro 9.1, utilizing the Ecoinvent 3.6 database for background emissions data. Grid electricity mix scenarios for different regions (EU, US, UAE) were incorporated to evaluate the influence of energy sources on environmental outcomes. Carbon pricing was also integrated into the economic assessment to assess how policy mechanisms could influence hydrogen refueling costs. Additionally, variations in grid electricity carbon intensity were analyzed to explore how increasing renewable energy penetration impacts the overall environmental benefits of hydrogen refueling stations

Techno-economic analysis determined the minimum hydrogen refueling price (MHRP) as $8.40/kgH₂ for Case 1 and $8.35/kgH₂ for Case 2 (Figure 1(b)). Given that utility-scale battery prices are projected to decline significantly by 2050 (Cole & Karmakar, 2023, NREL), the economic advantage of BESS is expected to improve further. The investment cost breakdown revealed that battery storage contributes a substantial portion of the capital cost in Case 1, whereas hydrogen compression and high-pressure storage dominate the cost structure in Case 2. Sensitivity analysis (Figure 1(c)) identified refueling capacity and discount rate as the most influential economic parameters, surpassing the effects of electrolyzer cost or tax rate. Specifically, reducing the refueling capacity to 500 kg/day led to a 28% increase in MHRP, while increasing capacity to 1,500 kg/day resulted in a 12% decrease, highlighting economies of scale as a key factor. Electricity prices were also a crucial determinant, with grid-dependent hydrogen production sites experiencing higher cost volatility.

Figure 1(d) compares the MHRP across different regions (US, EU, UAE) and refueling capacities (500, 1,000, and 1,500 kg/day). The US had the highest MHRP across all capacities, reaching $10.79/kgH₂ at 500 kg/day, whereas the EU had the lowest at $6.71/kgH₂ at 1,500 kg/day. Increasing the refueling capacity significantly reduced MHRP, but with diminishing returns beyond 1,000 kg/day due to additional infrastructure and operational costs. The differences in regional MHRP values stem from varying electricity costs, financial incentives for renewable energy, and local hydrogen market maturity. Hydrogen refueling stations in Europe benefit from extensive policy support and lower electricity carbon intensity, making the overall cost structure more competitive compared to other regions. The UAE, despite having low electricity costs, exhibited a relatively high MHRP due to infrastructure development constraints and limited hydrogen demand at present.

The environmental impact assessment focused on the Global Warming Potential (GWP, kg CO₂/kg H₂) across different regions and electricity sources. Among regions, the EU recorded the lowest GWP (8.94 kg CO₂/kg H₂) due to a cleaner electricity mix, while the UAE showed the highest (11.88 kg CO₂/kg H₂) despite its low electricity cost (Figure 1(e)). Figure 1(f) further demonstrates that the compression and refueling stages significantly contribute to total emissions when fossil-based electricity is used. Coal-powered electricity increased GWP to 17.40 kg CO₂/kg H₂, whereas renewable sources such as hydro (0.07 kg CO₂/kg H₂) and wind (0.36 kg CO₂/kg H₂) reduced emissions by up to 99%. The results highlight the necessity of transitioning to low-carbon electricity sources for hydrogen production and refueling to fully realize the environmental benefits of hydrogen infrastructure. Notably, hydrogen compression and refueling contributed a significant share of emissions in grid-dependent scenarios, underscoring the importance of decarbonizing not just production, but also downstream processes.

To provide a holistic economic-environmental perspective, an integrated TEA-LCA framework incorporated carbon pricing into the cost analysis (Figure 1(g)). The integrated minimum hydrogen refueling price (iMHRP) showed that fossil-based electricity sources significantly increased overall costs. Coal-based power resulted in an iMHRP of $10.20/kg H₂ for Case 1, while renewable sources such as photovoltaic and hydro maintained iMHRP below $8.50/kg H₂. The impact of carbon pricing was particularly evident in regions with high fossil fuel dependency, suggesting that stronger policy measures could accelerate the economic viability of green hydrogen. These results underscore the importance of balancing economic and environmental factors when selecting energy storage strategies and highlight the role of policy interventions in making hydrogen refueling cost-competitive with conventional fuels.

In conclusion, this study quantitatively compared two energy storage strategies—battery-based and hydrogen-based—within a renewable-powered hydrogen refueling station through integrated TEA and LCA methodologies. While the per-unit difference in cost and emissions between Case 1 and Case 2 was modest, the analysis revealed that scaling to full-station capacity amplifies the economic and environmental impact. Furthermore, cost drivers such as electricity prices, refueling capacity, and carbon pricing play a critical role in shaping overall feasibility. These findings support the need for a regionally optimized strategy that considers not only the storage method but also local energy mixes and policy structures. Ultimately, this study demonstrates that evaluating energy storage in the context of renewable hydrogen infrastructure provides meaningful guidance for deploying economically viable and environmentally sustainable hydrogen solutions at scale.

References

[1] Gong C, Na H, Yun S, Kim YJ, Won W. Liquid hydrogen refueling stations as an alternative to gaseous hydrogen refueling stations: Process development and integrative analyses. eTransportation 2025;23:100386.

[2] Tüysüz H. Alkaline water electrolysis for green hydrogen production. Acc Chem Res 2024;57(4):558-567.

[3] Amin M, Shah HH, Bashir B, Iqbal MA, Shah UH, Ali MU. Environmental assessment of hydrogen utilization in various applications and alternative renewable sources for hydrogen production: A review. Energies 2023;16(11):4348.

[4] Boretti A, Castelletto S. Hydrogen energy storage requirements for solar and wind energy production to account for long-term variability. Renew Energy 2024;221:119797.

[5] International Energy Agency. Global Hydrogen Review 2024. Paris: IEA; 2024.

[6] Wang J, Yang J, Feng Y, Hua J, Chen Z, Liao M, et al. Comparative experimental study of alkaline and proton exchange membrane water electrolysis for green hydrogen production. Appl Energy 2025;379:124936.

[7] Nnabuife SG, Darko CK, Obiako PC, Kuang B, Sun X, Jenkins K. A comparative analysis of different hydrogen production methods and their environmental impact. Clean Technol 2023;5(4):1344-1380.

[8] Cole W, Karmakar A. Cost projections for utility-scale battery storage: 2023 update. National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL); 2023. NREL/TP-6A20-87784.