2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(668e) Dual-Stimuli Responsive Polymers for Lower-Energy CO? Capture: Investigating Humidity- and Temperature-Effects

Authors

Understanding the aspects of DAC technology is crucial for cost reduction and scalability. A key component in this process is the type of sorbent used. Estimates suggest that sorbents contribute between 3% and 32% of the total DAC costs. Furthermore, a 2018 report from the National Academy of Sciences indicates that the capital cost of sorbents can account for 20% to 90% of the overall expenses related to air capture [9-11]. Therefore, designing optimal sorbents is a critical step toward making DAC technology more affordable.

Solid sorbents are often preferred in carbon capture technologies due to their improved kinetics and reduced tendency to lose volatiles [12]. Companies like Climeworks and Global Thermostat utilize amine-functionalized polymer sorbents that can absorb CO2 in both dry and wet environments. To release the captured CO2 and return to equilibrium, thermal energy is applied in a process known as the thermal swing mechanism. Typically, these sorbents require temperatures between 80 and 120 °C to desorb CO2, with heats of sorption ranging from 60 to 80 kJ/mol making it both energy- and cost-intensive [5,13].

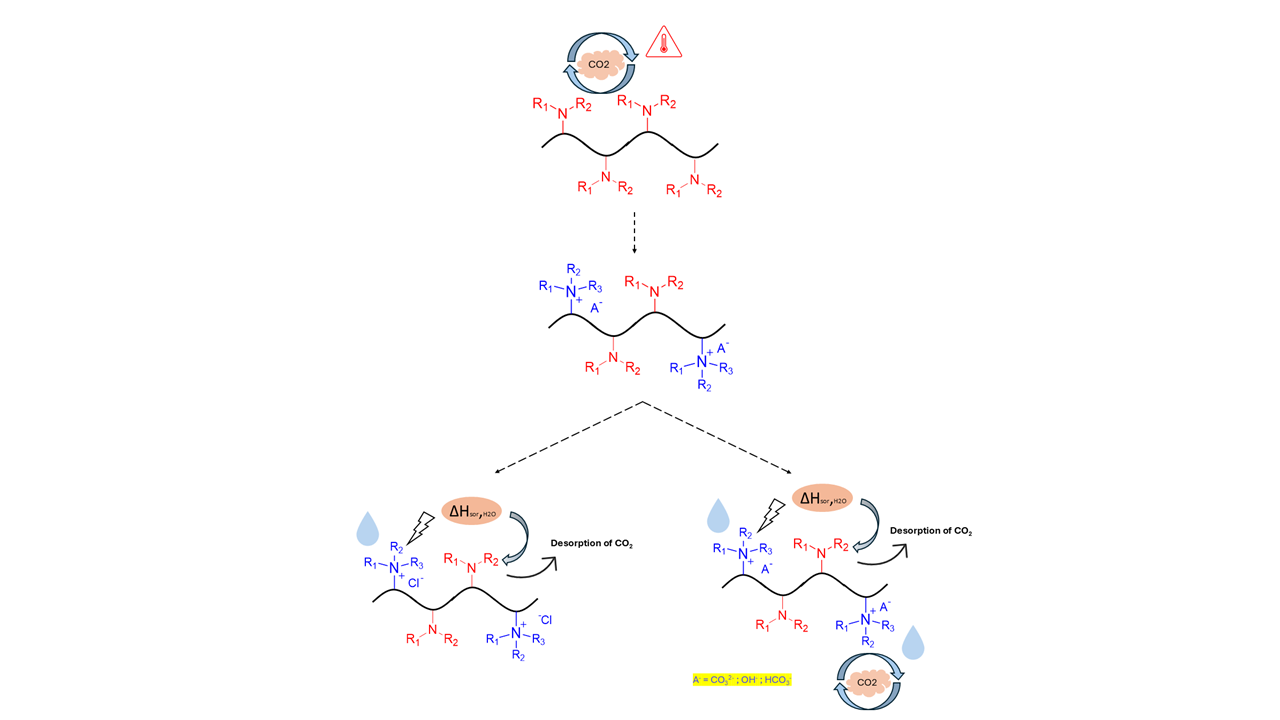

To address the high energy costs associated with regeneration, Prof Dr. Lackner proposed a novel technique called moisture swing [14]. This method involves controlling the sorption process through moisture levels. Many moisture-swing sorbents are strong basic ion-exchange resins containing quaternary ammonium ions (NR4+) paired with carbonate, bicarbonate, or hydroxide counter-ions. These sorbents can adsorb CO2 in dry conditions and release it in wet conditions. The interaction between the sorbents and water molecules alters their affinity for CO2, providing the energy needed for the sorption process. As a result, moisture-swing techniques require less energy compared to thermal swing methods [9]. Previous studies have reported sorption capacities for most moisture-swing sorbents ranging from 0.3 to 3.14 mmol CO2/g. But most sorbents have significantly lower than typical thermal-swing sorbents [15].

Driven by the demand for novel and adaptable sorbents with enhanced capacities and lower regeneration energies, this work focuses on developing hybrid polymers with amine and quaternary ammonium functionalities. These functionalities respond to CO₂ under different humidity and temperature conditions. Along with that, previous research has indicated that the electrostatic fields within charged quaternary ammonium polymers lead to high heats of water sorption, ranging from approximately 63 to 69 kJ/mol, which exceeds the latent energy of condensation, estimated to be around 42 kJ/mol. We hypothesize that the combination of adjacent quaternary ammonium and amine sites will generate excess heats of water adsorption, and this heat could potentially drive the desorption of CO2 from amine-tethered sites without or reducing the need for external energy input for regeneration. This current research focuses on designing copolymers using methacrylate-based tertiary amines (which serve as a CO2/thermal responsive site) and styrene-based quaternary ammonium (which functions as a CO2/humidity responsive site) with various counter-ions and investigate the effects of temperature and humidity on the CO2 sorption capacities of these polymers.

References:

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S. L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y. IPCC 2021.

- Chauvy, R.; Dubois, L. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 10320–10344.

- US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2021; 2023.

- Li, G.; Yao, J. Eng 2024, 5, 1298–1336.

- McQueen, N.; Gomes, K. V.; McCormick, C.; Blumanthal, K.; Pisciotta, M.; Wilcox, J. Energy 2021, 3 (3), 032001.

- Sodiq, A.; Abdullatif, Y.; Aissa, B.; et al. Technol. Innov. 2023, 29, 102991.

- Sinha, A.; Realff, M. J. AIChE J. 2019, 65, e16607.

- Duan, X.; Song, G.; Lu, G.; et al. Today Sustain. 2023, 23, 100453.

- Shi, X.; Xiao, H.; Azarabadi, H.; Song, J.; Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Lackner, K. S. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 6984–7006.

- Sinha, A.; Darunte, L. A.; Jones, C. W.; Realff, M. J.; Kawajiri, Y. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 750–764.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2019.

- Oyenekan, B. A.; Rochelle, G. T. AIChE J. 2007, 53, 3144–3154.

- Sabatino, F. Joule 2021, 5, 2047–2076.

- Lackner, K. S. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2009, 176, 93–106.

- Wang, T.; et al. Purif. Technol. 2023, 324, 124489.