2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(185r) Dry-Processed Lithium-Ion Battery Cathodes Using Aramid Nanofibers as Non-Fluorinated Binders

Authors

Traditional lithium-ion battery electrode manufacturing relies on slurry-based processing, wherein active materials (such as NMC), conductive additives (typically carbon black), and polymeric binders (commonly polytetrafluoroethylene) are dispersed in organic solvents like N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP). This mixture is cast onto current collectors and then dried to evaporate the solvent. While this process is mature and industrially scalable, it presents major environmental, safety, and economic drawbacks. NMP is a toxic, high-boiling-point solvent that is both carcinogenic and hazardous to handle, requiring complex solvent recovery systems and stringent occupational controls[1]. Moreover, PVDF, a fluorinated polymer, is chemically inert and non-degradable, raising concerns over end-of-life recyclability and environmental persistence[2].

In response to these issues, the battery community has increasingly sought greener binder systems and dry processing strategies that can reduce or eliminate toxic solvents, lower energy consumption, and simplify production workflows. However, PVDF remains dominant due to its strong adhesion, chemical stability, and compatibility with various cathode materials. Substituting PVDF with non-fluorinated binders that maintain or improve performance in a scalable manner remains a key challenge[3].

In this context, aramid nanofibers (ANFs) present an exciting opportunity as a next-generation binder material. Aramids, such as Kevlar, are a class of high-performance polymers known for their exceptional mechanical strength, high thermal stability (degradation above 500 °C), chemical resistance, and intrinsic rigidity due to their aromatic backbone and hydrogen-bonded amide linkages[4]. When processed into nanofibers, aramids retain their structural advantages while gaining processability and high surface area, enabling strong interfacial interactions with both active particles and conductive additives. This results in excellent particle binding and mechanical robustness, even at low binder loadings[5]. Unlike PVDF, aramid nanofibers are free of fluorine and do not require a solvent like NMP for processing. More importantly, their intrinsic rigidity and fibrous morphology open the door to binder architectures compatible with dry or semi-dry processing, eliminating the need for full solvent evaporation steps. Despite these advantages, their use as LIB binders is still in its early stages, and research on their integration into dry cathode architectures remains sparse.

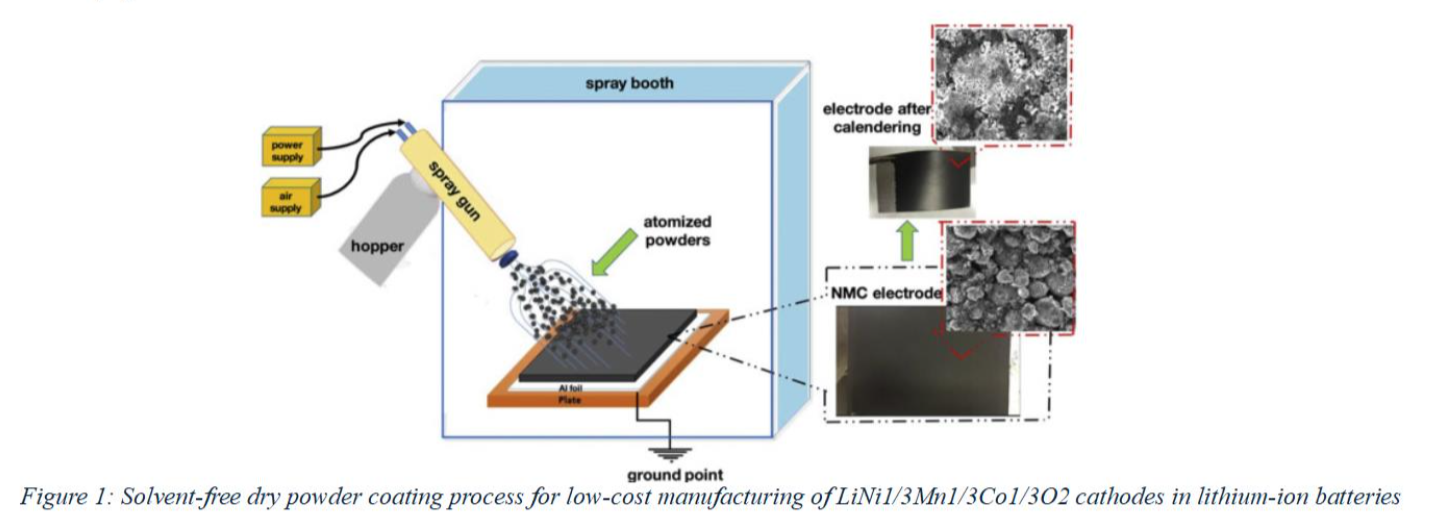

To fully harness the potential of ANFs in sustainable battery manufacturing, we explore their use in combination with Electrostatic Spray Deposition (ESD) - a dry or near-dry coating method that offers precise control over thickness, morphology, and composition. In ESD, a high-voltage electric field atomizes a precursor solution into charged droplets, which are directed onto a substrate to quickly form an electrode film (shown in Fig 1). This method enables solvent reduction, layer-by-layer control, and conformal coatings without lengthy drying times or vacuum systems[6]. It is also naturally scalable to roll-to-roll processes, making it appealing for industrial battery production.

Recent studies have demonstrated the promise of ESD for creating high-performance LIB electrodes. For instance, Uzun et al. showed that dry-sprayed NMC cathodes retained electrochemical performance while exhibiting improved porosity and uniformity[7]. Similarly, Tao et al. reported enhanced rate capability and mechanical integrity in ESD-fabricated electrodes[8]. However, most of these efforts still rely on conventional PVDF binders, limiting the environmental gains of the process.

In our work, we combine aramid nanofibers with dry electrostatic spray deposition to fabricate cathodes that are both fluorine-free and solvent-free. We start by preparing a dilute ANF dispersion in DMSO and blend it with NMC811 and conductive carbon black at desired ratios. This mixture is then electrostatically sprayed onto aluminum foil current collectors under optimized conditions. Following deposition, the electrode is briefly heated to remove residual solvent and enhance binder activation. The resulting cathodes are mechanically robust, show strong adhesion to the current collector, and maintain a uniform microstructure. Preliminary electrochemical testing indicates comparable capacity retention and cycling performance to PVDF-based controls, while completely avoiding the use of NMP or any fluorinated component. Morphological analysis via SEM and AFM confirms a well-interconnected network of ANF strands binding the NMC and carbon particles effectively. Furthermore, our approach enables fine-tuning of cathode porosity and thickness, crucial for balancing energy and power density.

This work highlights the feasibility and advantages of using aramid nanofibers as a sustainable binder platform for lithium-ion battery cathodes. Coupled with dry spray deposition techniques like ESD, ANFs offer a path forward for scalable, fluorine-free, and environmentally benign electrode manufacturing. Our method eliminates the hazards associated with NMP, simplifies solvent recovery requirements, and opens possibilities for recyclable or degradable binder formulations in the future. Ultimately, this strategy contributes toward more sustainable and industrially relevant battery technologies, aligning with global goals for clean energy, safety, and responsible manufacturing.

References:

[1]. Wang et al., Journal of Power Resources, 2012(29), 263-271.

[2]. Gao et al., Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 2024(54), 1285–1305.

[3]. Sheng Shui Zhang, Journal of Power Resources, 2007(164), 351-364.

[4]. Flouda et al., ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2021(13), 34807-34817.