2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(329h) Digital Twin Model Development for Catalytic CO? Methanation

Authors

In such systems, a plug flow reactor facilitates the dynamic conversion of CO₂ and H₂ to CH₄ and H₂O, governed by coupled transport phenomena and reaction kinetics. Efforts to directly integrate this process with offshore wind turbines, operating in remote, disturbance-prone environments, highlight both the need and the challenges of deploying DTs. The system's sensitivity to fluctuating inputs (e.g., intermittent renewable power) and complex multiphase dynamics make it an ideal test case for DT frameworks.

These challenges require models that not only replicate system behavior but also conform to specific operational constraints. To meet these requirements, four criteria define effective DT models: (i) predictive capability, (ii) computational efficiency coupled with numerical stability to enable real-time execution, (iii) adaptability to evolving data, and (iv) generalizability. These models prioritize "fit-for-purpose" accuracy [2] over maximum precision, aligning with industrial needs where rapid decision-making outweighs exhaustive simulation.

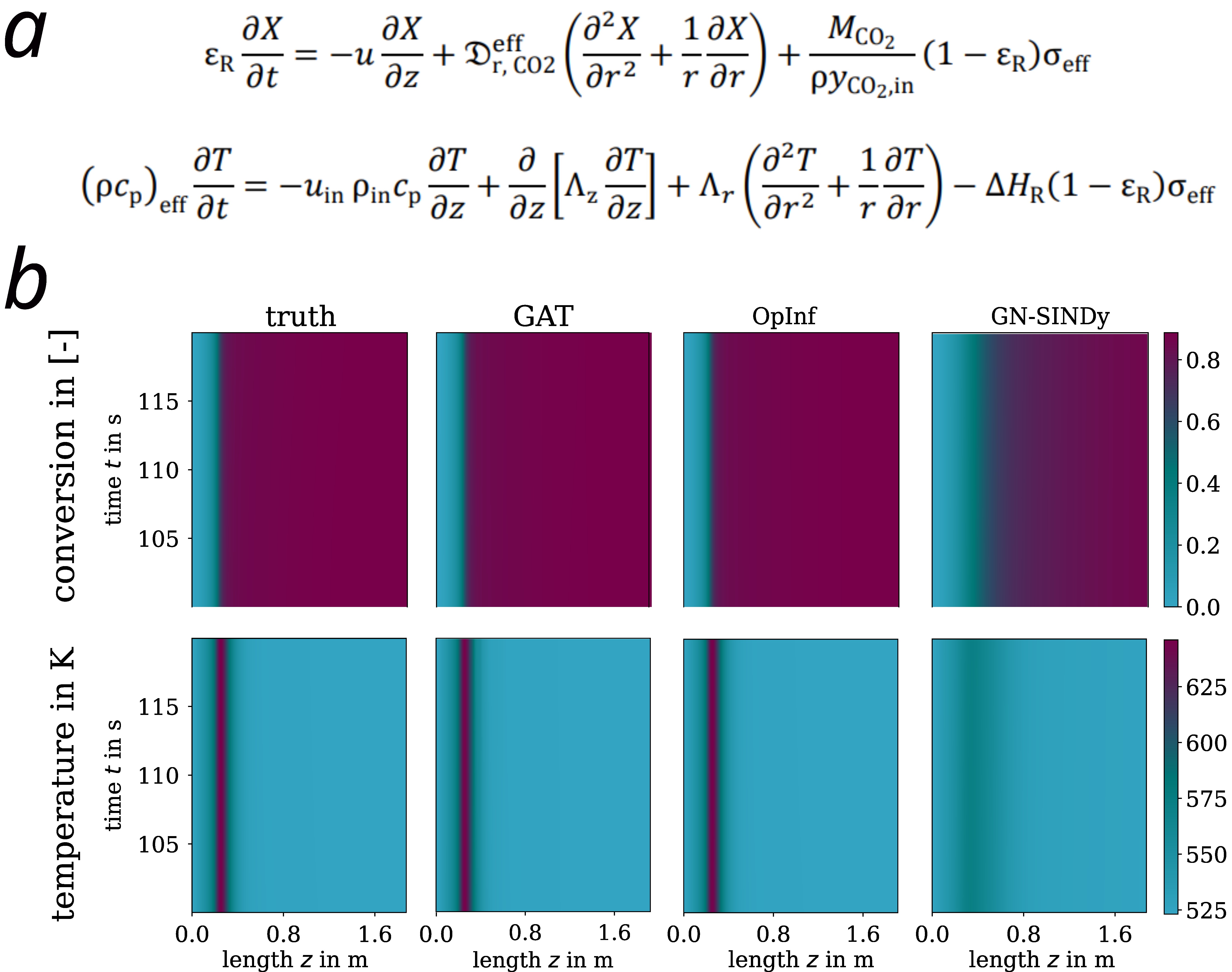

Traditional mechanistic models have long been used to capture the detailed physics of such processes. For example, the spatially resolved mass and energy balances for a catalytic CO₂ methanation reactor - expressed in terms of time (t) and spatial coordinates (z, r) - are shown in Fig. 1a, following the framework established in [3]. Here, X denotes the degree of CO₂ conversion and T the temperature. These equations provide predictive insight into reactor dynamics and allow parameter estimation through calibration. However, their computational complexity remains a fundamental barrier to real-time use.

To mitigate this, advanced numerical strategies can be employed: stiff ODE solvers use structured Jacobians to linearize and accelerate convergence, while higher-order discretization methods such as orthogonal collocation reduce spatial approximation errors through polynomial interpolation at strategically chosen nodes. In addition, adaptive time stepping optimizes computational complexity by adjusting step sizes based on local error estimates. But even with these refinements, persistent challenges remain. Frequent parameter updates - essential for adaptability - introduce prohibitive computational costs, and the inherent complexity of mechanistic models requires expert intervention to maintain stability and portability across operational scenarios.

To address these limitations, surrogate modeling has emerged to balance computational efficiency. By approximating the input-output behavior of high-dimensional systems, surrogate models retain essential dynamics while dramatically reducing complexity. Three broad categories dominate the field: statistical data-fit models, model order reduction (MOR), and simplified models. Guided by our fourth criterion-generalizability-we focus on non-intrusive, data-driven approaches that avoid system-specific assumptions and ensure adaptability to diverse operational regimes.

We evaluate three surrogate techniques applied to the catalytic CO₂ methanation reactor, each representing a different methodological paradigm. To assess generalizability, the models were trained on four different operational scenarios (e.g., changing flow rates and cooling temperature) and tested on unseen future data [4]. The predictions of all surrogate models, along with the ground truth, are shown in Fig. 1b for both CO₂ conversion and temperature.

- Spatio-temporal Graph Neural Networks (ST-GNNs) [5]: ST-GNNs are purely data-driven architectures that learn spatio-temporal relationships through two core mechanisms: graph structures encode spatial dependencies (nodes represent reactor locations, edges model adjacency relationships), while temporal attention mechanisms dynamically weight critical time steps in sequential data. In benchmarks, they achieved an average relative Frobenius error —used to measure matrix discrepancies— of <0.3 % when trained on the full dataset (>10,000 samples). While our current implementation prioritizes accuracy over speed, further optimization could improve computational efficiency for real-time use.

- Operator Inference (OpInf) [6]: This non-intrusive MOR technique projects high-dimensional dynamics onto a low-dimensional subspace via PCA and infers quadratic polynomial operators via regression. With a mean relative Frobenius error of <0.3 %, OpInf reduced the computational cost by an order of magnitude compared to full-order models. Notably, it was the only method that met all four criteria of predictive accuracy, efficiency, adaptability, and robustness, although its performance depends on careful subspace selection.

- Greedy Nonlinear System Identification (GN-SINDy) [7]: GN-SINDy identifies sparse governing equations via sequential thresholded regression, recovering dominant terms with only 0.02 % of the data points. While interpretable and data efficient, its average relative Frobenius error reached up to 6.5 %, capturing basic dynamics but struggling with finer transients.

Critically, these surrogate models are entirely data-driven and require no prior mechanistic knowledge. Given sufficient sensor coverage to resolve key variables (e.g., temperature, and conversion), they can be calibrated and validated directly from measurements - an advantage in systems where empirical data are more accessible than first-principles understanding.

While our results highlight the potential of numerical tools and surrogate models, further work is needed to integrate them into full-scale DTs. Key steps include parameterizing surrogates over broader operating windows and embedding mechanisms for quantifying uncertainty. With such refinements, these models could enable more efficient and flexible monitoring of complex processes, supporting the transition to resilient, data-centric industrial systems.

Figure 1. (a) Spatially resolved governing equations (mass and energy balances) for the catalytic CO₂ methanation reactor. (b) Surrogate model predictions (GAT, OpInf, GN-SINDy) compared to ground truth for CO₂ conversion and temperature profiles. Models were trained on transient dynamics (including flow rate variations and cooling temperature changes) and evaluated through multi-step prediction of future system states. The test trajectories show progression toward steady-state conditions, while training data captures more complex transient dynamics.

[1] Peterson L, Gosea IV, Benner P, Sundmacher K. Digital twins in process engineering: An overview on computational and numerical methods. Comput Chem Eng 108917 (2025) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2024.108917

[2] Ferrari A, Willcox KE. Digital twins in mechanical and aerospace engineering. Nat Comp Sci 4.3 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-024-00613-8

[3] Zimmermann RT, Bremer J, Sundmacher K. Load-flexible fixed-bed reactors by multi period design optimization. Chem Eng J 428:130771 (2022) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.130771

[4] Peterson L, Forootani A, Sanchez Medina EI, Gosea IV, Benner P, Sundmacher K. Towards Digital Twins for Power-to-X: Comparing Surrogate Models for a Catalytic CO2 Methanation Reactor. TechRxiv (2024) https://doi.org/10.36227/techrxiv.172263007.76668955/v1

[5] Veličković P, Cucurull G, Casanova A, Romero A, Lio P, Bengio Y. Graph attention networks. arXiv 1710.10903 (2017) https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1710.10903

[6] Kramer B, Peherstorfer B, Willcox KE. Learning nonlinear reduced models from data with operator inference. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 56:521-548 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-121021-025220

[7] Forootani A, Benner P. GN-SINDy: Greedy sampling neural network in sparse identification of nonlinear partial differential equations. arXiv 2405.08613 (2024) https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.08613