2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(101c) A Design for Circularity Strategy Is Not Always Environmentally Beneficial: Shifting from Aluminum to Steel Frames for U.S. Photovoltaics Modules

Authors

To this end, we present the first comprehensive lifecycle assessment (LCA) to evaluate the environmental tradeoffs between four material choices for PV frames – primary aluminum, secondary aluminum, primary steel, and secondary steel. For the primary supply chain, we account for 98 smelting plants, 15 frame manufacturing facilities, 36 module manufacturing facilities, and 4500 utility-scale PV installation sites. For the secondary supply chain, we account for 4500 PV decommissioning sites, 30 PV recycling plants, 2300 scrap collection facilities, 250 secondary smelting and refining facilities, and 15 frame manufacturing facilities. We also account for the inventory requirements, transportation distances, and electricity mixes used in the different processes in the primary and secondary supply chain (listed above). The chosen functional unit for this study is “1 m2 of a solar PV module”. As the primary focus of this LCA is the structural frame of the module, normalizing to 1 m² of module area allows for eliminating the inconsistencies arising from the varying dimensions of PV modules commonly found in the industry.

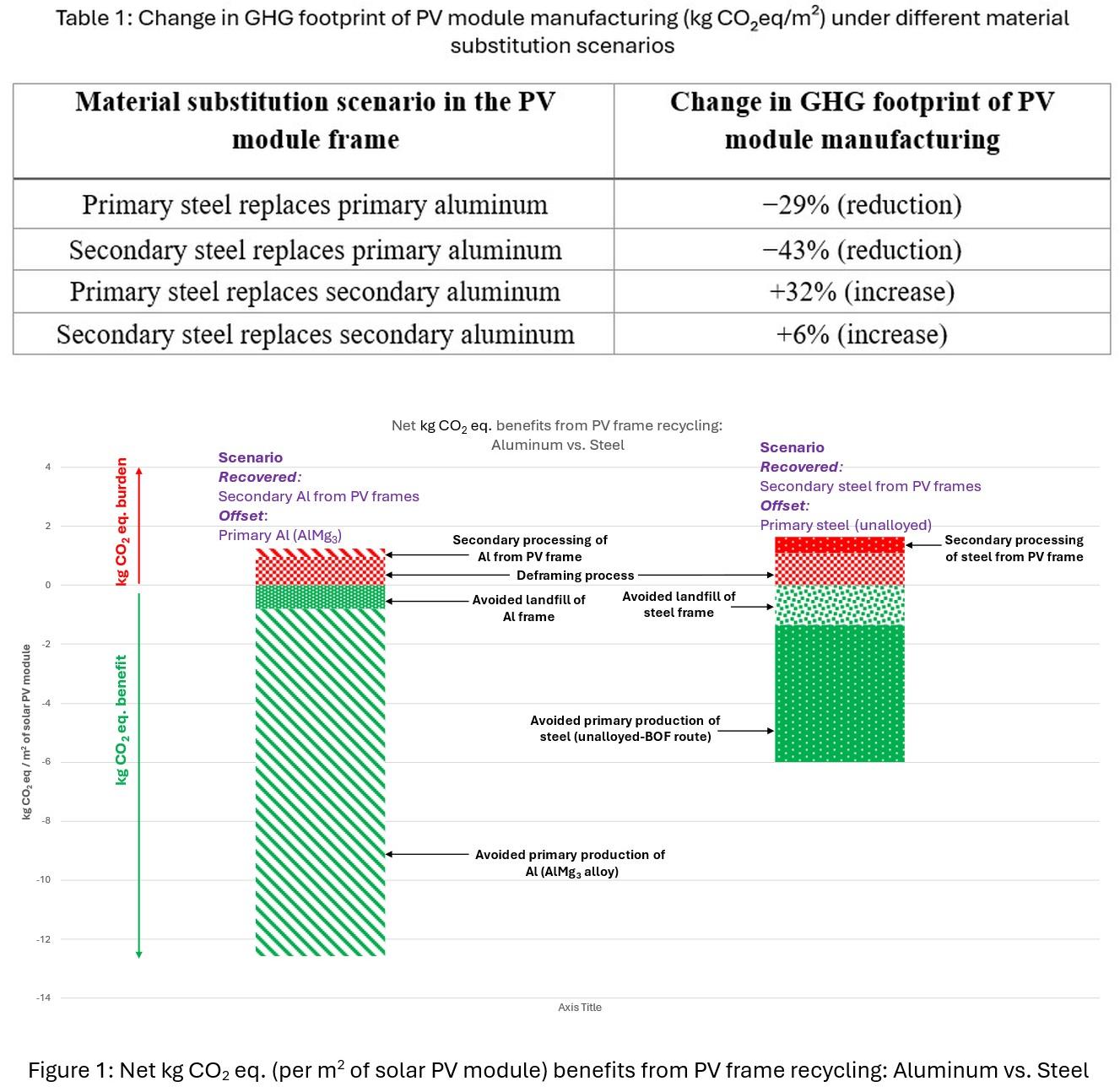

Excluding transportation distances, the analysis reveals that incorporating DfC strategies can either increase or decrease the greenhouse gas (GHG) footprint of PV module manufacturing, depending on the material substitution. As shown in Table 1, replacing primary aluminum with primary steel or secondary steel leads to significant reductions in GHG emissions per square meter of PV module, with the most significant reduction (43%) achieved when secondary steel replaces primary aluminum. However, not all DfC-driven substitutions result in emission reductions. For instance, replacing secondary aluminum with either primary steel or secondary steel increases the GHG footprint of PV module manufacturing—by 32% and 6%, respectively

Furthermore, we explore the environmental benefit when the metal recovered from a recycled PV module offsets the primary production of that metal. In this scenario, stand-alone PV module recycling shows that modules with aluminum frames offer a higher net carbon benefit—11.3 kg CO₂ eq per m²—compared to those with steel frames, which provide 4.3 kg CO₂ eq per m². (Figure 1)

However, including transportation distances across the primary and secondary supply chains significantly changes the relative environmental preferences of the four material choices. The impact of the transportation distances is depicted visually through an environmental preference graph, which identifies cut-off points and bounded regions wherein a material is preferable to the other three alternatives. Using a geographic information system (GIS) analysis, we depict the environmentally preferable material alternative to manufacture frames for PV modules to be installed in utility plants across the US map based on the geospatial spread of the supply chain process for the four material alternatives. Furthermore, we demonstrate how DfC strategies have a policy implication by quantifying how the US-manufactured PV modules with frames made from the four-material alternatives either meet or fail to meet the ultralow carbon PV standards defined specifically for US PV manufacturers.

REFERENCES

[1] “Steel Module / RSFM - Qcells North America.” Accessed: Apr. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://us.qcells.com/q-peak-duo-rsf-xl-g11-bfg/

[2] “Series 7 - Made in America, for America.” Accessed: Apr. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.firstsolar.com:443/en/Products/Series 7

[3] “Products_Module Series_HJT Hyper-ion Module.” Accessed: Apr. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://en.risen.com/assembly/hjt

[4] A. Lennon, M. Lunardi, B. Hallam, and P. R. Dias, “The aluminium demand risk of terawatt photovoltaics for net zero emissions by 2050,” Nat. Sustain., vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 357–363, Apr. 2022, doi: 10.1038/s41893-021-00838-9.

[5] “About steel,” worldsteel.org. Accessed: Mar. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://worldsteel.org/about-steel/

[6] “Environmental Impact Report | Origami Solar, Inc.” Accessed: Aug. 13, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://origamisolar.com/environmental-impact-report/

[7] W. Mackenzie, “Carbon neutrality goal forces Chinese aluminium smelters away from captive coal power.” Accessed: Apr. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.woodmac.com/press-releases/carbon-neutrality-goal-forces-ch…

[8] “Iron and Steel Statistics and Information | U.S. Geological Survey.” Accessed: Apr. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center/iron-…

[9] “Aluminum Statistics and Information | U.S. Geological Survey.” Accessed: Feb. 24, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center/alumi…

[10] “Alcoa’s Massena Operations Earns Certification from Aluminium Stewardship Initiative (ASI).” Accessed: Apr. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://news.alcoa.com/press-releases/press-release-details/2022/Alcoas…