2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(275c) Design and Implementation of an Automated Heart-on-a-Chip

Authors

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the US. Patients with CVD face chronic symptoms requiring lifelong pharmaceutical usage. On the other hand, cardiovascular toxicity is a leading cause of drug candidate failure. New drug development is extremely slow, with success rates in the drug discovery pipeline abysmally low. Organs-on-a-chip (OOC) aim to improve drug development by bridging the gap between in vitro screening and in vivo/clinical testing. These novel platforms comprise microfluidic channels that support a 3D culturing environment, heterogeneous cell populations, and biophysical stimuli. Combining organs-on-a-chip with advancements in stem cell differentiation creates a powerful model for drug development. However, combining human cells in a microfluidic channel is insufficient to change the drug development process. Further optimization of OOC towards high-throughput and automated systems is needed before the mass adoption of the technology.

Traditional OOCs are constructed via soft lithography with PDMS. The usage of PDMS is beneficial for cell viability in microchannels but will absorb lipophilic compounds, adding a confounding variable to dose-dependent pharmaceutical trials. New techniques developed in the lab utilize the “laser cut and assemble” method to fabricate our microfluidic platforms using optically clear thermoplastics and commercially available adhesives. Previous models have been restricted to cardiomyocyte and fibroblast co-cultures in a single chamber. Our fabrication technique allows for continuous culturing regions with distinct cell populations. This culturing technique allows for studying more complex cell interactions like neuron innervation and monitoring individual cell types. Current continuous imaging systems are expensive and have limited throughput capacity, requiring the development of alternative systems. Leveraging our optically clear systems, we have developed a fiber optic system that continuously monitors a desired fluorophore in situ without constant human interaction. The presented work shows we have been able to co-culture human-derived cardiomyocytes and neurons in a “12-well” format with automated culturing and fiber optic sensing.

Materials and Methods:

The heart OOC platform consists of the following layers: a top 3/16” PMMA cover with access ports to the media channel, a 1/16” PMMA layer providing the depth of the media channel, a 10 μm PET membrane (1 μM pore size) to serve as the interface between the media channel and the cell culture space, a 60 μm layer of 3M tape, a 76 μm PET GelPin to create distinct but continuous chambers in the chip, a 120 μm layer of 3M tape, and a glass coverslip to enclose and allow imaging of the cell culture region.

Cardiomyocyte differentiation follows Lian et al (2013). After differentiation, the immature cardiomyocytes are transduced with an AAV to express GCaMP. Posterior central nervous system (pCNS) neurons are sourced from Dr. Nisha Iyer at Tufts University.

The cardiomyocyte chamber was seeded with approximately 1×10^6 cells suspended in 20 μl of gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) hydrogel precursor. This hydrogel precursor comprises 7.5% w/v (cardiomyocyte) or 5% w/v (neuron) of GelMA, 0.5% w/v LAP, and the desired volume of cell culture media. The precursor is crosslinked using 405 nm light for 60 seconds. Following the polymerization in the cardiomyocyte chamber, the neurons are seeded at 1×10^5 cells in 10 μl of GelMA precursor per neuron chamber, which is also polymerized for 60 seconds. The single-channel heart chip was seeded and cultured by hand, while the high-throughput heart chip was seeded and cultured with Opentrons’ Flex Robot.

Pharmaceutical testing utilizes an Axio Z1 inverted microscope from Zeiss. Using the incubated stage with 5% CO2, we record 30-second video recordings of a region within the chip. These recordings are taken every 20 minutes for approximately 3 hours. Two time points are collected before dosing to establish a pre-dosed beat rate. The videos are processed using a custom MATLAB program to calculate mean beat rate, synchronicity, and number of beating regions.

The fiber optic photometry platform consists of commercially sourced parts that fit within a 30-square-centimeter footprint. An LED excitation beam passes through a series of filters and a dichroic mirror before passing through an objective. The beam is focused through a 7-fiber bundle leading to the heart chip. The emission of the fluorophores travels back through the fiber and dichroic mirror before hitting a CMOS camera. The recorded emission is processed and further analyzed using custom Python code.

Results and Discussion:

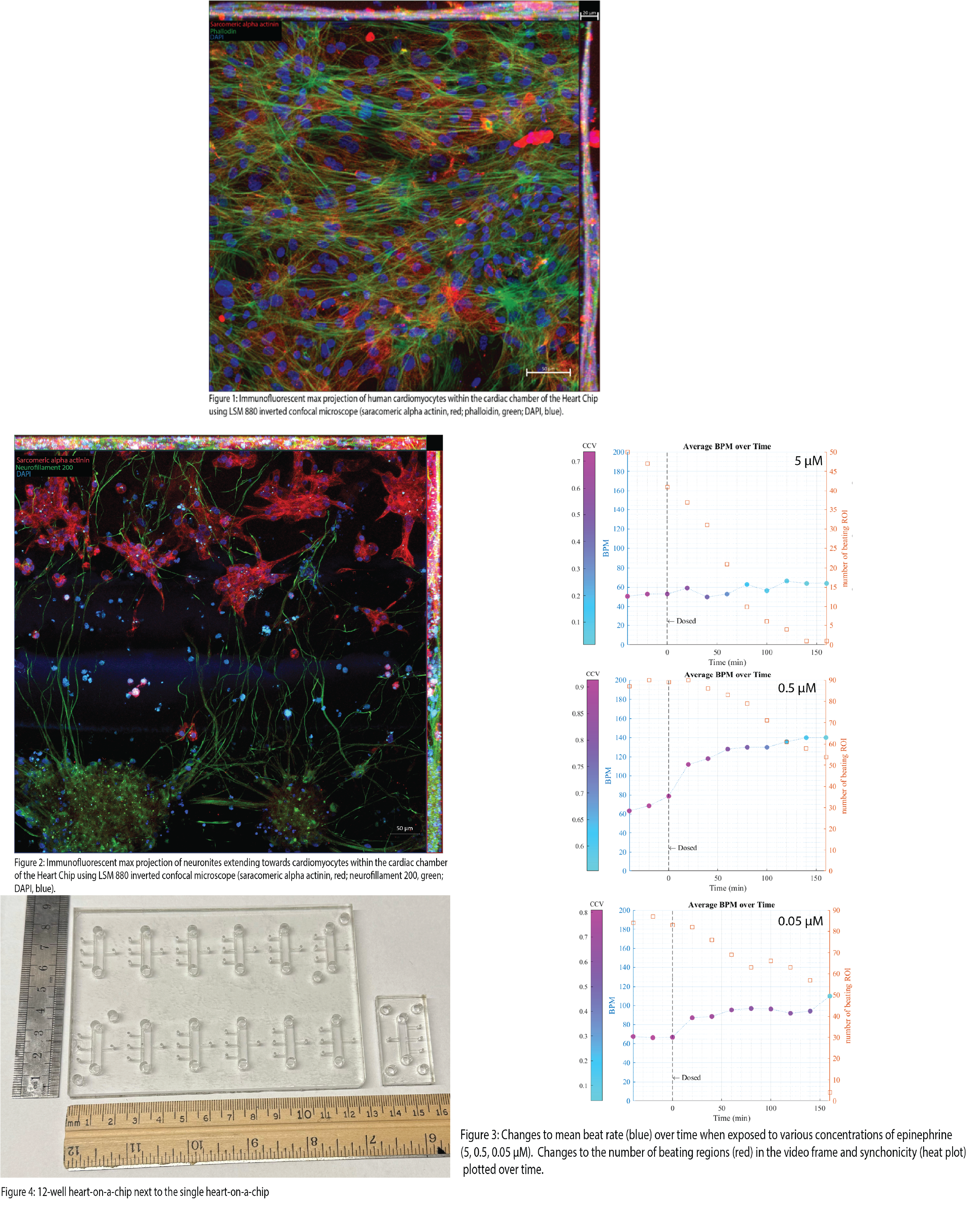

After differentiation, the cardiomyocytes spontaneously contract within their wells. This phenotype persists within the organ chip, indicating that the microenvironment suits their long-term culture. A heart chip cultured for three weeks was fixed and stained to investigate the structure and network of seeded cardiomyocytes (Figure 1). Immunofluorescent staining shows that cardiomyocytes readily network with one another and display morphology similar to in vivo. Further work has shown that pCNS neurons readily extend neurites from the neuron chamber into the cardiac chamber and intertwine around cardiomyocytes (Figure 2). The intertwining is indicative that synapses are forming. However, further validation is needed to show synaptic formation. Pharmaceutical testing on the heart chip has yielded surprising results. Dosing a single heart chip with 5 μM epinephrine showed no change in mean beat rate, counter to the expected result of increased mean beating. Further characterization of the dosing included synchronicity and the number of beating regions. The inclusion of these variables showed that the cultures were being affected by epinephrine, just exhausting cardiomyocytes due to the high concentration of epinephrine (Figure 3). Follow-up work showed that the increase in mean beating was achieved when the dose was dropped. The workflow for the single heart chip was cumbersome and time-consuming for only testing one parameter and at one concentration. Using this frustration as inspiration, we developed an automated system to increase throughput. We took the base footprint of the single heart chip and expanded it to the size of a typical well plate, containing 12 of the single heart chip “units” (Figure 4). An automated imaging apparatus was developed to overcome the time dedicated by a human operator to live image the chip during drug dosing. This system utilizes fiber optic photometry and GCaMP-induced cardiomyocytes to approximate the mean beat rate. We are collecting a bulk beating value of the tissue, while the previous method got cellular resolution. However, combining the fiber optic setup with an Arduino and a motorized stage allows us to collect data on the “12 well” heart nearly continuously between media changes with minimal human manipulation. The combination of human-derived cell types, near-continuous data recording, inclusion of automation, and increased throughput are improvements on previous models and incorporate useful characteristics for industrial adoption.