2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(393d) Deriving Personalized and Optimized Estrogen Dosage Profiles for Optimal Endometrium Thickness for Embryo Implantation

Authors

Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART) encompass infertility treatments that involve the handling of eggs or embryos [7]. In vitro fertilization (IVF), the most frequently recommended ART procedure, involves fertilizing egg cells (oocytes) with sperm in a laboratory setting, followed by the transfer of the resulting embryos back into the patient's uterus. IVF typically proceeds in four stages: superovulation, egg retrieval, fertilization, and embryo transfer [4]. During the final stage, embryo transfer, or implantation, the embryo attaches to the uterine endometrial lining.

Adequate preparation of the endometrium is crucial for successful embryo implantation. Several endometrial preparation protocols exist, including hormone replacement therapy (HRT) with or without GnRH-a suppression, true natural cycle (t-NC) with or without luteal phase support, modified natural cycle (modified-NC) with or without luteal phase support, and mild ovarian stimulation (Mild-OS) [9]. While the ideal endometrial thickness for these protocols remains undefined, a correlation between increased endometrial thickness and higher pregnancy rates is often observed [5, 8]. One study indicated that live birth rates (LBR) in fresh cycles improved with an endometrial thickness of 10-12 mm, whereas LBR in frozen cycles plateaued between 7 and 10 mm [1]. Although pregnancy is still possible outside this range, a consensus suggests that an endometrial thickness of 8 mm or greater is optimal, with IVF outcomes typically poorer below 7 mm. An endometrial thickness below 7 mm is considered thin and is associated with decreased clinical pregnancy rates (CPR) and LBR, as well as an increased risk of preterm delivery and miscarriage [9, 11].

Currently, HRT often involves administering a fixed daily dose of 6 mg of estradiol or an increasing dose (2 mg/day on days 1-7, 4 mg/day on days 8-12, and 6 mg/day from day 13 until embryo transfer), with estradiol priming lasting 10 to 36 days. Once the endometrial thickness exceeds 7 mm, progesterone supplementation is initiated and continues until the lute-placental shift, around the 10th to 12th week of gestation [9]. If the endometrium remains thin, various methods can be employed to increase its thickness, including administering hormones, vasoactive agents, or growth factors [5]. Increasing the dosage and duration of estradiol is the most common approach and will be the focus of this paper.

Despite the existence of general estrogen dosing guidelines, these are not tailored to individual patient needs. Our group recently developed a differential-algebraic model for endometrium thickness. This model can be personalized using data from two days of monitoring. This personalized model can then be optimized using optimal control theory. The minimum effective amount of estrogen can be administered by optimizing estrogen dosing to reach the desired endometrial thickness. This approach may help reduce IVF treatment costs and mitigate potential adverse effects associated with hormone administration, such as reduced insulin sensitivity, hypertriglyceridemia, and gut microflora disturbances [3].

Methodology

The general mathematical technique used to solve optimal control problems includes calculus of variations, Pontrygin’s maximum principle, and dynamic programming. Nonlinear programming (NLP) optimization methods can also be applied to such problems if the system can be discretized into a nonlinear algebraic equation. We present here the maximum principle formulation as it involves ordinary differential equations unlike calculus of variations or dynamic programming.

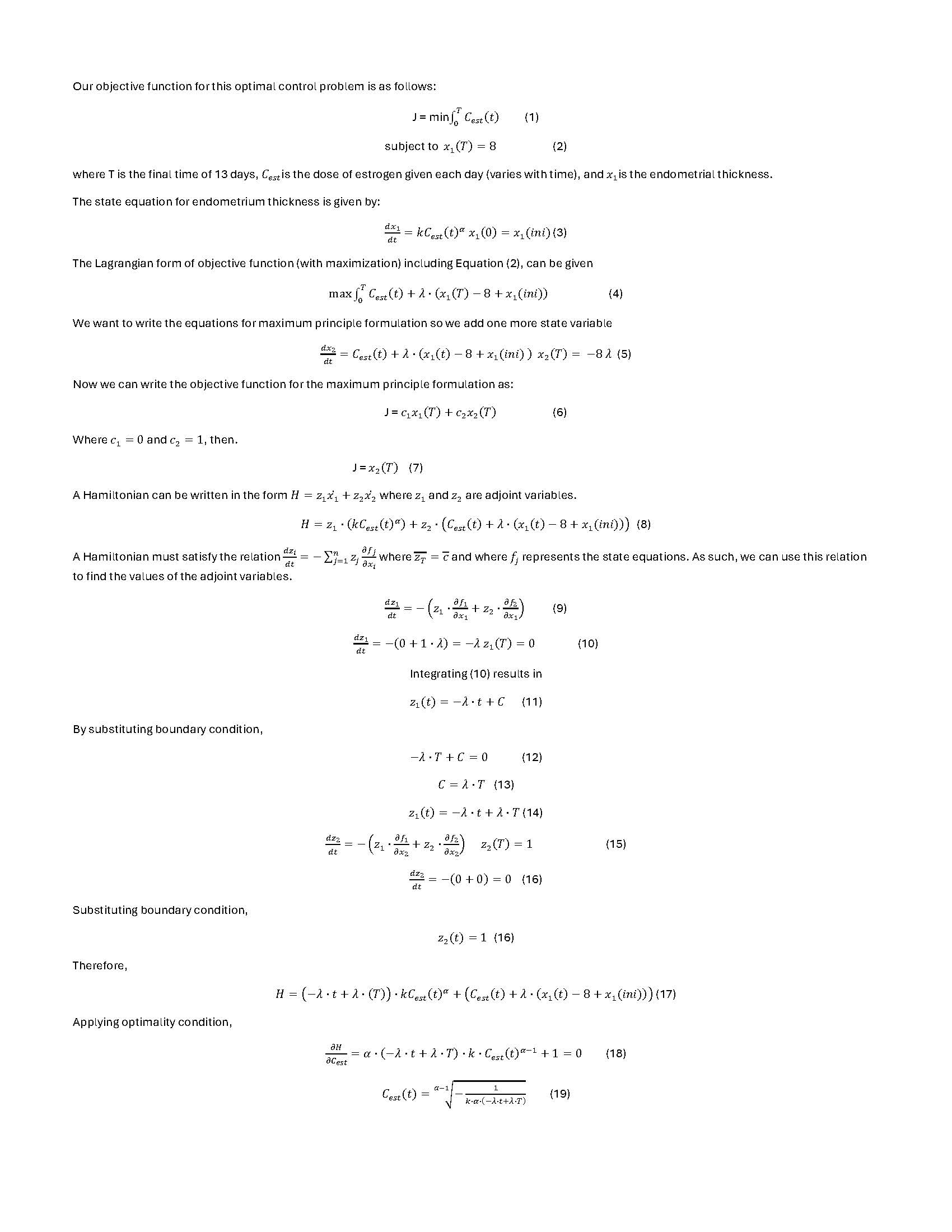

Our objective function for this optimal control problem is as follows:

J = min (1)

subject to (2)

where T is the final time of 13 days, is the dose of estrogen given each day (varies with time), and is the endometrial thickness.

The state equation for endometrium thickness is given by:

(3)

The Lagrangian form of objective function (with maximization) including Equation (2), can be given

(4)

We want to write the equations for maximum principle formulation so we add one more state variable

(5)

Now we can write the objective function for the maximum principle formulation as:

J = (6)

Where and , then.

J = (7)

A Hamiltonian can be written in the form where and are adjoint variables.

(8)

A Hamiltonian must satisfy the relation where and where represents the state equations. As such, we can use this relation to find the values of the adjoint variables.

(9)

As

(10)

Integrating (10) results in

(11)

By substituting boundary condition,

(12)

(13)

(14)

(15)

(16)

Substituting boundary condition,

(16)

Therefore,

(17)

Applying optimality condition,

(18)

(19)

It can be seen that we have the dosage profile as a function of . The other condition this problem should satisfy is the constraint on final thickness, Equation (2). We want to find such that the constraint is satisfied. This involves an iterative loop for on the top of the maximum principle formulation, providing an analytical equation for the profile.

Expected Results

We have data from 41 patients and personalized model parameters for these patients. We will compare the results of our optimal control profile to those of the current dosage given. We already have the results of solving this problem using nonlinear programming optimization. We will also compare these maximum principle results with those of nonlinear programming formulation.

Acknowledgments: This work was funded by NSF supplemental grant 2335090.

Bibliography:

- boulghar, M. A., & Aboulghar, M. M. (2023). Optimum endometrial thickness before embryo transfer: an ongoing debate. Fertility and sterility, 120(1), 99–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2023.04.013

- Asch Schuff, R. H., Suarez, J., Laugas, N., Zamora Ramirez, M. L., & Alkon, T. (2024, April 24). Artificial intelligence model utilizing endometrial analysis to contribute as a predictor of assisted reproductive technology success | Published in Journal of IVF-Worldwide. Journal of IVF-Worldwide. https://jivfww.scholasticahq.com/article/115893-artificial-intelligence…

- Coussa, A., Hasan, H., & Barber, T. (2020, March 25). Impact of contraception and IVF hormones on metabolic, endocrine, and inflammatory status. NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7311610/

- Diwekar, Urmila, et al. “Customized modeling and optimal control of superovulation stage in in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment.” Control Applications for Biomedical Engineering Systems, edited by Ahmad Taher Azar, Elsevier Science, 2020.

- Eftekhar, Maryam, and Sara Zare Mehrjardi. “The correlation between endometrial thickness and pregnancy outcomes in fresh ART cycles with different age groups: a retrospective study - Middle East Fertility Society Journal.” Middle East Fertility Society Journal, 18 December 2019, https://mefj.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s43043-019-0013-y#citeas.

- Eftekhar, M., Tabibnejad, N., & Alsadat Tabatabaie, A. (2018, March). The thin endometrium in assisted reproductive technology: An ongoing challenge. Middle East Fertility Society Journal, 23(1), 1-7. ScienceDirect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mefs.2017.12.006

- Graham, M. E., Jelin, A., Hoon, A. H., Jr, Wilms Floet, A. M., Levey, E., & Graham, E. M. (2023). Assisted reproductive technology: Short- and long-term outcomes. Developmental medicine and child neurology, 65(1), 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.15332

- Kovacs, P., Matyas, S., & Boda, K. (2003). The effect of endometrial thickness on IVF/ICSI outcome. Human Reproduction, 18(11), 2337-2341. https://academic.oup.com/humrep/article/18/11/2337/644897

- Papanikolaou, E. G., Oduwole, O. O., Peltoketo, H., & Huhtaniemi, T. (2021, July 9). Preparation of the Endometrium for Frozen Embryo Transfer: A Systematic Review.Frontiers. Retrieved July 4, 2024, from https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/endocrinology/articles/10.3389/fen…

- Prato, Luca Dal et al. “Endometrial preparation for frozen-thawed embryo transfer with or without pretreatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist” Fertility and Sterility, Volume 77, Issue 5, 956 – 960

- Zheng, Y., Chen, B., Dai, J., Xu, B., Ai, J., Jin, L., & Dong, X. (2022, November 10). Thin endometrium is associated with higher risks of preterm birth and low birth weight after frozen single blastocyst transfer. NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9685422/

12. Diwekar U., Introduction to Applied Optimization, 3rd Edition, (2020) Springer