2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(542e) CRISPR Editing of the Cancer Glycocalyx to Tune Mechanically Regulated Migration in Glioblastoma Multiforme

Authors

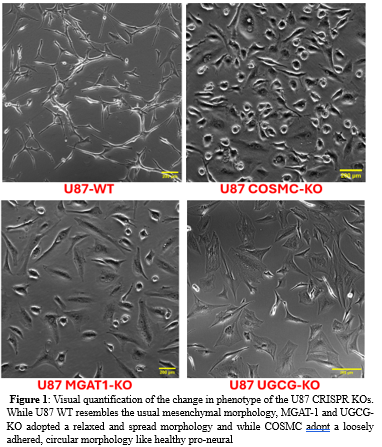

Materials and Methods: CRISPR plasmids with gRNA sequences against human COSMC, UGCG and MGAT1 in the pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (PX458) V2.0 vector were generated and COSMC-KO (U87-COSMC-KO), MGAT1-KO (U87-MGAT1-KO) and UGCG-KO (U87-UGCG-KO) single KO cell lines were created by chemically transfecting the WT U87s with these vectors using lipofectamine 3000TM reagent. To characterize the KOs, the region surrounding the CRISPR target site was amplified from genomic DNA and specific deletions confirmed. Approximately 6 weeks after transfection, morphological changes were quantified by microscopy with firmly adherent, spindle like cells being more aggressive and mesenchymal GBMs and loosely attached, more rounded cells being pro-neural and less aggressive. Then we fashioned polyacrylamide gels at a range of stiffnesses (400-60,000 Pa) conjugated with Fibronectin and monitored if the knockouts migrate differently than the controls and if the stiffness affects the migration of the GBMs. Next, we checked to see if the signaling (FAK) is altered in any of the GBM knockouts through the use of tyrosine specific activated antibodies (Tyr397 FAK and pFAK) on both the wild type and mutants to check changes in signaling profiles and response to mechanical cues.

Results: Microscopic observation (Figure 1) showed a trend towards a more pro-neural phenotype, as expected, in each of U87-COSMC-KO, and U-87-UGCG-KO and U87-MGAT1KO. What is more surprising is that U87-COSMC-KO and U-87-UGCG-KO showed the most robust trend as they were detached, less aggressive, and had the most recognizable proneural phenotype. This phenotype is seen more often in healthy cells, an observation that is expected to correlate with glycocalyx content and size upon quantification.

Conclusions, and Discussions: while both MGAT1 and UGCG KOs adopted a relaxed tension morphology, COSMC appear to be the most critical sugars responsible for GBM aggression. However, our ongoing experiments are quantifying the changes in surface topography and glycocalyx architecture as well as signaling and migration associated with the phenotypic changes seen in each KOs with the hope of identifying mucin or glycolipids as key players in GBM aggression. We plan to inject each of the KOs in mice to study tumor development and survival. Finally, we will check for immune and drug susceptibility for each KOs. This could ultimately lead to new potential therapies that could increase immune recognition and in improved patient prognosis in GBM.

Acknowlegement: This work was funded by NIH-NIGMS GM143357, Center for Engineering MechanoBiology, CEMB CMMI: 15-48571, NJIT Faculty Seed Grant and New Jersey Health Foundation (NJHF), Grant number: PC:26-24, to the cellular motion lab.