2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(32c) Controlled Cell-Material Interactions for Implant Fibrosis Prevention

Approximately 10% of the United States population has received an implantable medical device.1 Coupled with a global market size of over $100 billion in 2023, there is an impending need to ensure mitigation of accompanying pathologies with deleterious effects.2 Prevention of a chronic foreign body response (FBR) that either impairs implant performance or necessitates removal through excessive fibrotic tissue deposition, is often based in prophylactic surface modification of physical properties. Plasma treatment is a process which alters surface energy through replacement of terminal hydrogens with oxygen as to increase wettability and non-fouling behavior towards surrounding biomolecules.3 Surface texturing aims to increase local contact area and thus provide a three-dimensional architecture needed for cells to attach and proliferate.4 However, instruments deployed in these processes are still moderately expensive ($2,000-$5,000) for even simple benchtop units and are not specific to any specific cell type implicated in a chronic FBR.5 To address this lack of specificity and high startup cost, various functional moieties have been employed in both industry and academic settings.

Deposition of biological and synthetic polymers with surface-active properties provides a novel avenue for exploration. Hydroxyapatite has been deployed as a naturally occurring coating material for orthopedic implants due to improved osseointegration, while parylene is a synthesized hydrophobic alternative known to form conformal coatings and prevent corrosion.6,7 Although both coatings retain high success rates (>90%) in orthopedic surgical interventions for total joint replacement, long-term survival rates of these implants are very low (<50%) due to a chronic FBR occurring at the bone-implant interface.8 Polypropylene is a mainstay chemistry deployed in generation of mesh material for repair of hernia pathologies.9 Despite use of extracellular matrix (ECM) and other biopolymer coatings designed to enhance biocompatibility and non-stick behavior for polypropylene meshes, a 30% failure rate and estimated $10 billion in annual treatment costs necessitate further exploration.10,11 The goal of this research project is to innovate a low-cost and highly translatable implant coating material with high specificity to selectively inactivate chronic FBR cell phenotypes and prevent inhibitory implant fibrosis.

Approach:

To address this unmet clinical need, we will devise a novel coating material based on poly(ionic liquids) (PILs). In their monomer form, ionic liquids exhibit a propensity to interact with cell membranes and induce apoptosis for antimicrobial applications.12,13 Interestingly, this effect is greatly magnified upon polymerization of ionic liquid into a PIL macrostructure containing an increased number of positively and negatively charged ionic species.14 Such a material phenomena has been exploited in burn wound dressing applications designed to mitigate bacterial growth, but has yet to be integrated with other cell types.15,16 Exploitation of charge-based interactions in chronic FBR manipulation on implant surfaces has been presented in literature through layer-by-layer (LbL) fabrication of poly(electrolyte).17,18 However, LbL deposition of poly(electrolyte) multilayers presents translational complexities not present in a PIL coating based strategy.19,20

Inspiration for use of poly(ionic liquid) (PIL) as a material platform stems from a synergy of graduate work and postdoctoral work. Exposure to cell-material interfacial phenomena was explored during graduate work on development of sprayable antimicrobial burn wound dressings21 and anti-fibrotic adhesion barriers22,23. During postdoctoral work, we employed ionic liquids as excipients for high concentration protein formulations due to their intrinsic charge profiles and ability to screen colloidal interactions driving aggregation. However, one noted utility of ionic liquids not explored under the context of this work was their antimicrobial efficacy induced through their ability to alter cell membrane structure and morphology.

Innovation:

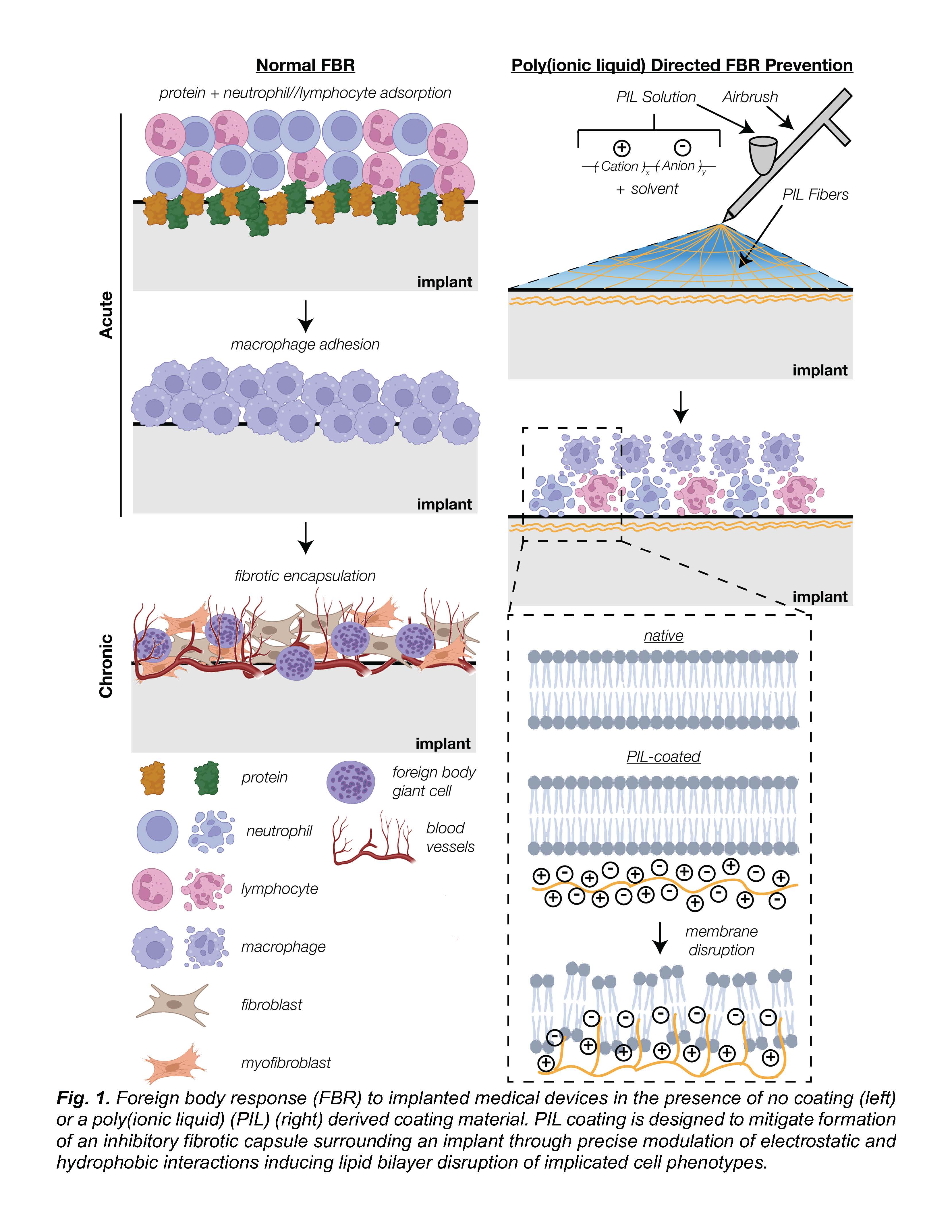

Poly(ionic liquid) (PIL) addresses the challenges presented by conventional implant coating materials in a manner of low-cost and high specificity towards macrophage and fibrotic cell types (Fig. 1). The initial hallmark of innovation will be in the synthesis of biocompatible, organic acid based PILs through reversible adddition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) co-polymerization of cationic and anionic monomers. Currently researched PIL membranes for antimicrobial applications deploy imidazolium monomers as a positively charged, cation component.14–16 However, counter anionic monomers in these PIL materials are presented in ionic (ex. bromide) rather than structured form (ex. carboxylic acid), leading to potential off-target toxicity and stability concerns for long-term usage. The second innovation in this platform is the tunability of material-to-cell interactions through modification of polymer properties. Alteration of copolymer ratio between cation and anion will dictate the balance of localization versus intercalation with a lipid bilayer of a cell membrane.12 Molecular weight upon polymerization is an additional parameter set to dictate both total charge density on implant surface and long-term degradation kinetics favorable to implant coatings in contrast to monomeric ionic liquid or other non-polymeric coatings. The third innovation of this research project will be in an optimized application method of coating material through a process of solution blow spinning (SBS). SBS-directed coating of medical implants retains an inherent advantage over conventional vapor deposition and LbL techniques methods due to facile and rapid formation of highly conformal polymer fibrous membranes.

Methodology:

Aim 1 Generate a library of sprayable poly(ionic liquids) with tunable cellular membrane interactive properties. The material space of poly(ionic liquids) (PILs) is limitless due to both the abundance of natural and synthetic cation and anion species, as well as the large number of relative ion ratio combinations. Hence, the goal in this aim will be to synthesize a library of PILs with variable chemistries and physical properties leading to refined control of their cell localization and membrane disruption capacities. We hypothesize that synthesis of PILs will yield a range of molecular weights, a variable affecting both sprayability and mechanical integrity of formed polymer membranes. Milestone 1: Synthesize a library of PILs with ranging amphiphilicity and molecular weights; Milestone 2: Determine spray deposition capacity of synthesized PILs via solution blow spinning; Milestone 3: Characterize time-based degradation profiles and mechanical strength of spray deposited PIL materials.

Aim 2 Establish a method to optimize poly(ionic liquid) delivery for fibrosis cell type inactivation. Foreign body response (FBR) to implanted materials is an intricate process with both acute and chronic stages. An initial acute stage is characterized by a cytokine signaling cascade leading to adsorption of proteins, neutrophils, and monocytes. A following chronic stage yields adsorption of M1/M2 macrophages capable of fibroblast activation and sequential collagen deposition. We hypothesize that poly(ionic liquids) (PILs) will present a range of localization and intercalation capabilities with FBR involved cell types based on their intrinsic cell morphology and membrane composition. Our goal in this aim is to further elucidate both the mechanism of action between cations and anions contained in a poly(ionic liquid) macrostructure, as well as qualify the efficacy of PILs in fibrosis prevention. Milestone 4: Quantify cell viability and apoptotic cell death pathways of PIL coated substrates for neutrophils, macrophages, and fibroblasts; Milestone 5: Quantify interaction mechanism between PIL and cells of interest via 1D/2D nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy techniques.

Aim 3 Assess safety and efficacy of optimized poly(ionic liquid) coating material in multiscale animal models. In vivo preclinical evaluation of safety and efficacy in animals is a necessary step prior to any human clinical trials of implant derived chronic FBR prevention. Orthopedic (30%) and hernia mesh (20%) implants are two high impact devices examples with elevated failure rates due to a chronic FBR. The goal of this aim will be to use optimized poly(ionic liquid) (PIL) formulations and combinations generated in Aims 1.1 and 1.2 and study extent of fibrotic tissue generation in chronic (survival) mouse and piglet models. Initial studies will focus on scar tissue prevention of PIL membranes without an implant material, followed by use of coated target devices such as metal alloy for an orthopedic implant model, or a polypropylene for a hernia mesh repair model. Milestone 6: Mouse peritoneal button model with tissue adhesive PIL coating; Milestone 7: Mouse tibia fracture model with PIL coated orthopedic implant; Milestone 8: Piglet hernia model with PIL coated mesh.

References:

1. Marwick C. Implant Recommendations. JAMA. 2000;283(7):869-869. doi:10.1001/jama.283.7.869-JMN0216-2-1. 2. Global Medical Implant Market Size, Forecast 2023 – 2033. Spherical Insights. Accessed May 31, 2024. https://www.sphericalinsights.com/reports/medical-implant-market

3. Liston EM. Plasma Treatment for Improved Bonding: A Review. The Journal of Adhesion. 1989;30(1-4):199-218. doi:10.1080/00218468908048206

4. Glocker D, Ranade S. Medical Coatings and Deposition Technologies. Scrivener Publishing. Published online 2016.

5. Harrick Plasma Basic Plasma Cleaner 115V. Accessed May 31, 2024. https://www.fishersci.com/shop/products/basic-plasma-cleaner-115v/NC933…

6. van Wachem PB, Hogt AH, Beugeling T, et al. Adhesion of cultured human endothelial cells onto methacrylate polymers with varying surface wettability and charge. Biomaterials. 1987;8(5):323-328. doi:10.1016/0142-9612(87)90001-9

7. Kuppusami S, Oskouei RH. Parylene Coatings in Medical Devices and Implants: A Review. ujbe. 2015;3(2):9-14. doi:10.13189/ujbe.2015.030201

8. Landgraeber S, Jäger M, Jacobs JJ, Hallab NJ. The Pathology of Orthopedic Implant Failure Is Mediated by Innate Immune System Cytokines. Mediators of Inflammation. 2014;2014:1-9. doi:10.1155/2014/185150

9. Wang See C, Kim T, Zhu D. Hernia Mesh and Hernia Repair: A Review. Engineered Regeneration. 2020;1:19-33. doi:10.1016/j.engreg.2020.05.002

10. Shubinets V, Fox JP, Lanni MA, et al. Incisional Hernia in the United States: Trends in Hospital Encounters and Corresponding Healthcare Charges. The American Surgeon. 2018;84(1):118-125. doi:10.1177/000313481808400132

11. Wise J. Hernia mesh complications may have affected up to 170 000 patients, investigation finds. BMJ. Published online September 27, 2018:k4104. doi:10.1136/bmj.k4104

12. Kumari P, Pillai VVS, Benedetto A. Mechanisms of action of ionic liquids on living cells: the state of the art. Biophys Rev. 2020;12(5):1187-1215. doi:10.1007/s12551-020-00754-w

13. Nikfarjam N, Ghomi M, Agarwal T, et al. Antimicrobial Ionic Liquid‐Based Materials for Biomedical Applications. Adv Funct Materials. 2021;31(42):2104148. doi:10.1002/adfm.202104148

14. Liu X, Chang L, Peng L, et al. Poly(ionic liquid)-Based Efficient and Robust Antiseptic Spray. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(41):48358-48364. doi:10.1021/acsami.1c11481

15. Zheng Z, Xu Q, Guo J, et al. Structure–Antibacterial Activity Relationships of Imidazolium-Type Ionic Liquid Monomers, Poly(ionic liquids) and Poly(ionic liquid) Membranes: Effect of Alkyl Chain Length and Cations. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(20):12684-12692. doi:10.1021/acsami.6b03391

16. Fang H, Wang J, Li L, et al. A novel high-strength poly(ionic liquid)/PVA hydrogel dressing for antibacterial applications. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2019;365:153-164. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2019.02.030

17. Ong ATL, Aoki J, Kutryk MJ, Serruys PW. How to accelerate the endothelialization of stents. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2005;98(2):123-126.

18. Sethi R, Lee C. Endothelial Progenitor Cell Capture Stent: Safety and Effectiveness. J Interven Cardiology. 2012;25(5):493-500. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8183.2012.00740.x

19. Macdonald ML, Samuel RE, Shah NJ, Padera RF, Beben YM, Hammond PT. Tissue integration of growth factor-eluting layer-by-layer polyelectrolyte multilayer coated implants. Biomaterials. 2011;32(5):1446-1453. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.052

20. Guzmán E, Rubio RG, Ortega F. A closer physico-chemical look to the Layer-by-Layer electrostatic self-assembly of polyelectrolyte multilayers. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 2020;282:102197. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2020.102197

21. Daristotle JL, Lau LW, Erdi M, et al. Sprayable and Biodegradable, Intrinsically Adhesive Wound Dressing with Antimicrobial Properties. Bioeng Transl Med. 2020;5(1). doi:10.1002/btm2.10149

22. Erdi M, Rozyyev S, Balabhadrapatruni M, et al. Sprayable Tissue Adhesive with Biodegradation Tuned for Prevention of Postoperative Abdominal Adhesions. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine. Published online May 23, 2022:e10335. doi:10.1002/btm2.10335

23. Erdi M, Saruwatari MS, Rozyyev S, et al. Controlled Release of a Therapeutic Peptide in Sprayable Surgical Sealant for Prevention of Postoperative Abdominal Adhesions. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. Published online March 8, 2023:acsami.3c00283. doi:10.1021/acsami.3c00283